Americans use the Book of Revelation to talk about immigration – and always have

A biblical scholar traces how images of the ‘city of God’ have shaped American culture – especially when it comes to who should be allowed into the country.

During a campaign speech in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, on Oct. 19, 2024, Donald Trump promised to save the country from immigrants: “I will rescue every town across America that has been invaded and conquered, and we will put these vicious and bloodthirsty criminals in a jail or kick them out of our country.”

Depicting immigrants as a threat has been a pillar of Trump’s message since 2015. And the types of terms he uses aren’t just disparaging. It might not seem like it, but Trump is continuing a long tradition in American politics: using language shaped by the Bible.

When the former president says those at the border are “poisoning the blood of our country,” “animals” and “rapists,” his vocabulary mirrors verses from the New Testament. The Book of Revelation, the last book of the Bible, says those kept out of the city of God are “filthy”; they are “dogs and sorcerers and sexually immoral and murderers and idolaters and everyone who loves and practices falsehood.”

In fact, Americans have been using the Bible for centuries to talk about immigrants, especially those they want to keep out. As a scholar of the Bible and politics, I’ve studied how language from Revelation shaped American ideas about who belongs in the United States – the focus of my book, “Immigration and Apocalypse.”

The shining city

The Book of Revelation describes a vision of the end of the world, when the wicked are punished and the good rewarded. It tells the story of God’s enemies, who worship the evil Beast of the Sea, bear his mark on their body and threaten God’s people. Because of their wickedness, they suffer diseases, catastrophes and war until they are finally destroyed in the lake of fire.

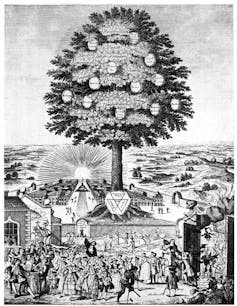

God’s followers, however, enter through the gates of the walls surrounding the New Jerusalem, a holy city that comes down from heaven. God’s chosen people enter through the gates and live in the shining city for eternity.

Throughout American history, many of its Christian citizens have imagined themselves as God’s saints in the New Jerusalem. Puritan colonists believed they were establishing God’s kingdom, both metaphorically and literally. Ronald Reagan likened the nation to the New Jerusalem by describing America as a “shining city … built on rocks stronger than oceans, wind-swept, God-blessed, and teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace,” but with city walls and doors.

Reagan was specifically quoting Puritan John Winthrop, one of the founders of Massachusetts Bay Colony, whose use of the “city on a hill” phrase quotes Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. But Reagan’s detailed description closely matches that of the New Jerusalem in Revelation 21. Like God’s heavenly city, Reagan’s picture of America also has strong foundations, walls and gates, and people from every nation bringing in tribute.

Barring the gates

If people imagine the U.S. as God’s city, then it’s easy also to imagine enemies who want to invade that city. And this is how unwanted immigrants have been depicted through American history: as enemies of God.

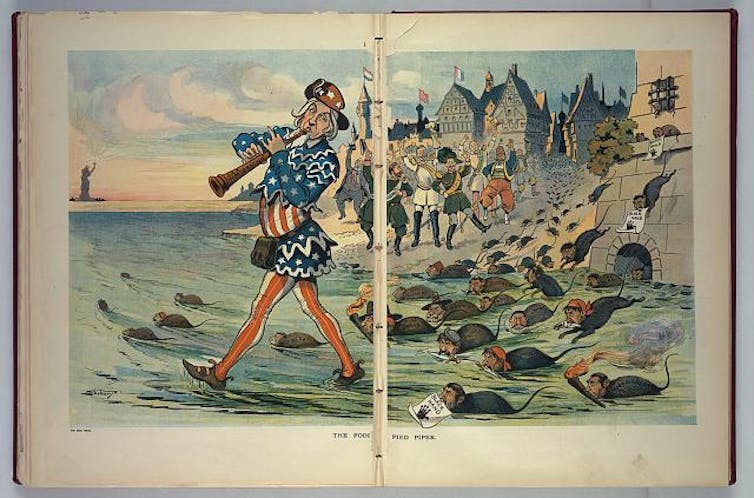

In the 19th century, when virtually all politicians were Protestant, anti-Catholic politicians accused Irish immigrants of bearing the “mark of the Beast” and being loyal to the “Antichrist”: the pope. They claimed that Irish immigrants could form an unholy army against the nation.

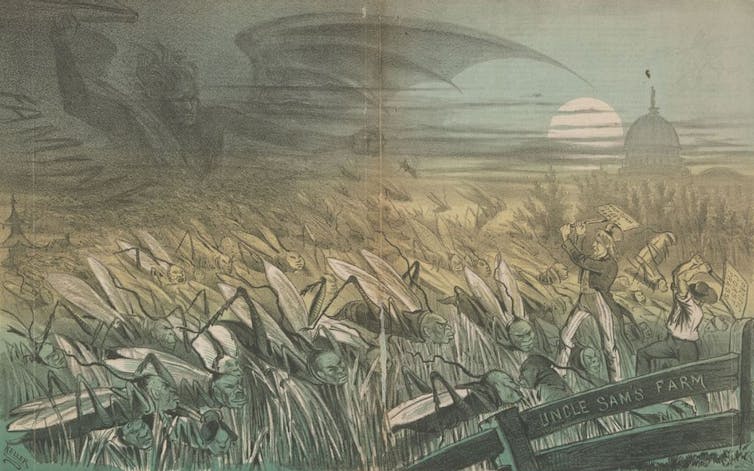

At the turn of the century, “yellow peril” novels against Chinese immigration imagined a heathen horde taking over the U.S. At the end of one such book, China itself is depicted as a satanic “Black Dragon,” forcing its way through “the Golden Gate” of America.

And all immigrant groups who were unwanted at one time or another have been accused of being “filthy” and diseased, like the enemies of God in Revelation. Italians, Jews, Irish, Chinese and Mexicans were all, at some point, targeted as unhealthy and carrying illness.

In political cartoons from the turn of the 20th century, Eastern European and Jewish immigrants were depicted as rats, while Chinese immigrants were portrayed as a horde of grasshoppers – echoing imagery from Revelation, where locusts with human faces swarm the Earth. During COVID-19, an event itself considered apocalyptic, xenophobic fear has focused on Asian Americans and migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border.

This constellation of labels from Revelation – plague-bearing, bestial, invading, sexually corrupt, murderous – has been reused and recycled throughout American history.

‘Heaven has a wall’

Trump himself has described immigrants as diseased, “not human,” sexual assaulters, violent and those “who don’t like our religion.”

Others have more explicitly used images from Revelation to talk about immigration. Pastor Robert Jeffress, who preached at Trump’s 2017 inauguration church service, told viewers on Fox News’ “Fox & Friends,” “God is not against walls, walls are not ‘un-Christian,’ the Bible says even heaven is going to have a wall around it.” The Conservative Political Action Conference held a panel in 2017 titled “If Heaven Has a Gate, A Wall, and Extreme Vetting, Why Can’t America?” There are even bumper stickers that say, “Heaven Has A Wall and Strict Immigration Policy / Hell Has Open Borders.”

Revelation 21 indeed describes the heavenly New Jerusalem with a massive shining wall, “clear as crystal,” with pearls for gates. Trump, similarly, talks about his “big, beautiful door,” set in a “beautiful,” massive wall that also has to be “see-through.”

The city of God metaphor has long been a tool for American leaders – both to idealize the nation and to warn against immigration. But the concept of a walled-in city seems increasingly outdated in a digitally connected, global world.

As migration continues to rise around the world due to climate change and conflict, I’d argue that these metaphors and the attitudes they drive are not just obsolete, but exacerbating crisis.

Yii-Jan Lin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Today’s obsession with authenticity isn’t new – being true to yourself has troubled philosophers for

Contemporary culture seems obsessed with authenticity – but the question of how to be ‘sincere’…

Measuring poverty on a spectrum instead of an arbitrary line conveys a more accurate picture of ineq

An economist proposes a new method of estimating the scope of poverty in different countries.

Family-friendly workplaces are great − but ‘families of 1’ get ignored

In an era of family-friendly workplaces, how can employers treat single people without kids fairly?