How HIV/AIDS got its name − the words Americans used for the crisis were steeped in science, stigma

The nascent LGBTQ+ rights movement and the Christian right each strongly shaped the early years of HIV/AIDS, a historian explains.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention first used the term “AIDS” on Sept. 24, 1982, more than a year after the first cases appeared in medical records. Those early years of the crisis were marked by a great deal of confusion over what caused the disease, who it affected and how it spread.

But the naming itself – acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, which we now know is caused by the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV – was a milestone. How people talked about and named the AIDS crisis shaped how it was viewed and either fostered or countered a culture of stigma.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, for instance, conservative Christian leaders such as Rev. Jerry Falwell described AIDS as “God’s punishment” for sexual immorality. Many AIDS activists, on the other hand, also took up the importance of naming. Instead of being called “AIDS victims,” they preferred phrases like “people with AIDS” to affirm their status as people rather than merely patients or victims.

As a historian of religion, sexuality and public health, I became interested in how moral and religious rhetoric shaped this global pandemic from the start. In my book “After the Wrath of God,” I trace how the AIDS crisis could not be separated from the broader cultural contexts in which it emerged, including the histories of LGBTQ+ people and the Christian right.

In other words, from the start, this medical epidemic was also a moral epidemic.

Before “AIDS”

The naming of AIDS in 1982 came more than a year after the CDC first reported cases of young, otherwise healthy men diagnosed with rare forms of cancer, pneumonia and other infections that occur in people with weakened immune systems.

CDC researchers searched for a connection and found that these men were “all active homosexuals.” This confirmed what many gay and bisexual men living in places such as New York City and San Francisco already knew: There was a mysterious illness affecting their community.

Early news coverage described a new “gay cancer” or “gay pneumonia.” Some medical researchers called it GRID – gay-related immune deficiency – or acquired community immune deficiency. When CDC leaders settled on AIDS instead, they wanted to acknowledge the prevalence of cases among many other groups, including heterosexuals.

Despite these efforts, however, this early association with homosexuality would stick.

In fact, the history of homosexuality was crucial to the very discovery of AIDS. Scientists have now shown that HIV circulated well before 1981, especially among intravenous drug users, many of whom were homeless. But unusual illnesses and deaths within this population largely went unnoticed.

Meanwhile, the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement had been picking up steam since 1969, when a police raid at the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York City, set off a series of riots that prompted a new wave of LGBTQ+ activism. By the 1980s, queer and trans people asserted greater political and cultural influence.

This visibility and increasing cultural influence were crucial to the detection of this new disease.

Stirring ‘God’s wrath’

The early association of AIDS with homosexuality also ensured that this public health crisis would stir moral and religious debate.

In the 1970s, conservative Christian leaders had already warned the broader public about what they considered to be an epidemic of homosexuality. They argued that social acceptance of LGBTQ+ people was a sign of moral decline, and warned that if the United States did not stamp out this “moral disease,” the country would face the same fate as Sodom and Gomorrah, biblical cities destroyed by God.

In other words, the Christian right already had its own way to talk about homosexuality as an epidemic, as a threat to society itself. The AIDS crisis seemed to only confirm their belief in God’s wrath.

Medical and public health officials were not immune to this rhetoric. In the 1980s, at hospitals across New York, people readily referred to WOGS – the wrath of God syndrome. A physician at the Medical College of Georgia penned an editorial for Southern Medical Journal that asked whether AIDS fulfilled a biblical pronouncement about “the due penalty” for sexual sins and recommended conversion therapy for homosexuals.

In the White House, as historian Jennifer Brier has shown, President Ronald Reagan’s conservative advisers Gary Bauer and William Bennett formulated a strategy to fight AIDS that emphasized the moral righteousness of heterosexuality and abstinence outside of marriage.

They were frustrated to get pushback from the Reagan-appointed Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, a pediatric surgeon who had also become one of the leaders of the evangelical pro-life movement. He insisted that national AIDS policy focus on comprehensive sex education.

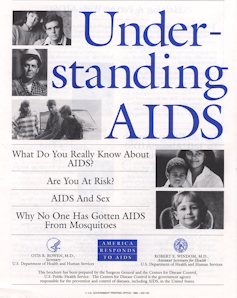

In 1988, Koop sent a mailer called Understanding AIDS to virtually every household in America. Conservatives balked at Koop’s approach, although he still prioritized abstinence for people who were unmarried as the best form of protection.

Bauer and Bennett complained that the flyer included information about condoms and described the risks of contagion through oral and anal sex. Phyllis Schlafly, the conservative Catholic crusader against feminism, abortion and gay rights, accused the surgeon general of trying to teach “safe sodomy” to third graders.

Beyond the Christian right

Not all conservative Christians understood AIDS to be God’s punishment for sexual sin. Many evangelical groups and Catholic leaders even pushed against that notion – yet still spoke of it in religious and moral terms.

Cardinal John O’Connor, the archbishop of New York, drew the ire of many AIDS activists when he spoke about AIDS at the Vatican in 1989. “Good morality,” he proclaimed, “is good medicine.”

Many Christians took more progressive positions. Southern Baptist ethicist Earl Shelp and chaplain Ronald Sunderland worked as research fellows at Texas Medical Center, where they first encountered people with AIDS. Together, they started one of the earliest AIDS ministry programs, which focused on helping gay men with AIDS without judgment.

And many queer and feminist Christian and Jewish leaders, including Jim Mitulski, Yvette Flunder and Yoel Kahn, forged queer-affirming and justice-oriented responses to the stigma of AIDS. They countered the idea that AIDS was a “gay disease,” but they also focused on how AIDS harmed populations that were often sidelined, including people of color, women and drug users.

What’s in a name?

Today, when I teach about the history of the HIV/AIDS crisis, my students tend to be confused by this early association with homosexuality. They associate AIDS with sub-Saharan Africa, which had become the epicenter of the pandemic by the 1990s.

Nevertheless, my students have grown up in a world where AIDS is far better understood. Thanks to the work of activists and scientists, far more people now know that HIV can be blocked by using condoms and sterile needles. Antiretroviral therapy has proven very effective in treating people able to obtain and tolerate the medicines.

Yet no matter how scientific or objective people hope to be, epidemics are shaped by culture. And studying that history helps us understand more about ourselves.

Anthony Petro does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Crowdfunded generosity isn’t taxable – but IRS regulations haven’t kept up with the growth of mutual

Some Americans are discovering that monetary help they received from friends, neighbors or even strangers…

Picky eating starts in the womb – a nutritional neuroscientist explains how to expand your child’s p

While genes do influence some food preferences, positive experiences can help make new tastes easier…

Algorithms that customize marketing to your phone could also influence your views on warfare

AI systems are getting good at optimizing persuasion in commerce. They are also quietly becoming tools…