Why Nepal had a religious monarchy − and why some people want it back

Many in Nepal are protesting to bring back the Hindu monarchy, which was dissolved in 2008. A scholar of South Asian religions explains what’s behind these protests.

Gyanendra Shah, former king of Nepal, will celebrate his 77th birthday on July 7, 2024. Twenty years ago, his birthday would have been a Nepalese national holiday. Indeed, when I first traveled to Nepal in 2001, the nation prided itself on being the “world’s last Hindu kingdom.” Every rupee note showed the king’s face. The national anthem sang his praise.

But between 2006 and 2008, Nepal transitioned from a Hindu monarchy to a secular democracy. It dissolved its monarchy completely, and Shah left the palace in June 2008. He has been living ever since as a private citizen.

In 2012, when I submitted my doctoral dissertation on the transition, it seemed that Nepal had decisively eliminated its monarchy and that Nepalis were gladly anticipating their secular future. But today many Nepalis are disillusioned with their multiparty democratic system. Following a major pro-monarchy rally in November 2023, Nepal’s capital has witnessed a series of modest but vocal follow-up demonstrations advocating a return to Hindu monarchy.

What had religious kingship looked like in Nepal? Why was it ended – and why do some people want it back?

Hindu monarchy

Unlike European monarchies, which were deeply connected to Christianity, Nepal’s monarchy was rooted in Hinduism. This meant the king of Nepal needed to be born into a Hindu family, and he needed to marry a Hindu woman. He needed to uphold family lineage rituals and worship in his ancestral shrine room. He also needed to have close relationships with Brahmin priests.

The modern palace hired a priestly Brahmin staff – salaried employees who reported daily to a palace office to do rituals. The king needed to honor major Hindu holidays by making public appearances and performing rituals. He surveyed the army on Shiva Ratri, a festival that honors Lord Shiva, and blessed government leaders during the Hindu festival of Vijaya Dasami. He received a blessing from his patron goddess Kumari, a young girl believed to be the manifestation of the Hindu goddess Taleju, during the festival of Indra Jatra.

These roles made the king the patriarch, protector and archetype of the nation. Even though for most of Nepal’s history the king was not directly running the government, in a common royalist phrase, the king was Nepal’s “ekata ka prateek”: the symbol of unity.

Consolidation of monarchy

Modern Nepal has existed for only about 250 years. For centuries, what is now Nepal was divided among many small principalities. In the 1760s, though, a minor local king conquered all his neighbors, relocated his capital to Kathmandu and set his dynasty on the throne. But after this ambitious and effective king, the descendants who followed were mostly weak and ineffective rulers. By 1800, the country was being governed in the king’s name by regents and self-appointed prime ministers.

In 1950, however, King Tribhuvan Shah, who had been serving a purely ceremonial role since 1922, formed an alliance with a budding democracy movement in order to step into more direct political power. From King Tribhuvan onward, Nepal’s kings would actively lead the government.

The modern monarchy was further centralized and consolidated by Tribhuvan’s son, King Mahendra, who ruled from 1955 to 1972. Urbane and cosmopolitan, he worked to modernize the country and his role as king. Meanwhile, he greatly expanded the idea of Hindu kingship. He also dissolved the country’s first democratically elected government in order to put himself in charge of the panchayat, an ostensibly grassroots democratic system that in reality was tightly controlled by the palace.

He also enacted a nationalistic program that would reshape a diverse Nepal into a single identity, around himself as the symbol of national unity. This program was summed up by the slogan “ek raja, ek bhesh, ek bhasa”: “One king, one country, one national-dress.”

Nepal’s dozens of minority languages and ethnic identities were suppressed in favor of a national culture around the king’s own religious, ethnic and language background. When children went to school, they would learn a carefully constructed curriculum, taught only in Nepali language, from books that praised Hinduism and the centrality of the royal family, from teachers dressed in the newly codified Nepali national outfit for men, the “daura suruwal.”

Modern nationalism thus meant a unified Nepal that erased ethnic, regional and religious differences in favor of the unity of the monarchy.

The monarchy crumbles

King Mahendra passed the throne to his eldest son, Birendra. But in June 2001, King Birendra was murdered in the palace, allegedly by his own son, along with his wife and children and half a dozen other members of the royal family. This event dealt a catastrophic blow to the monarchy.

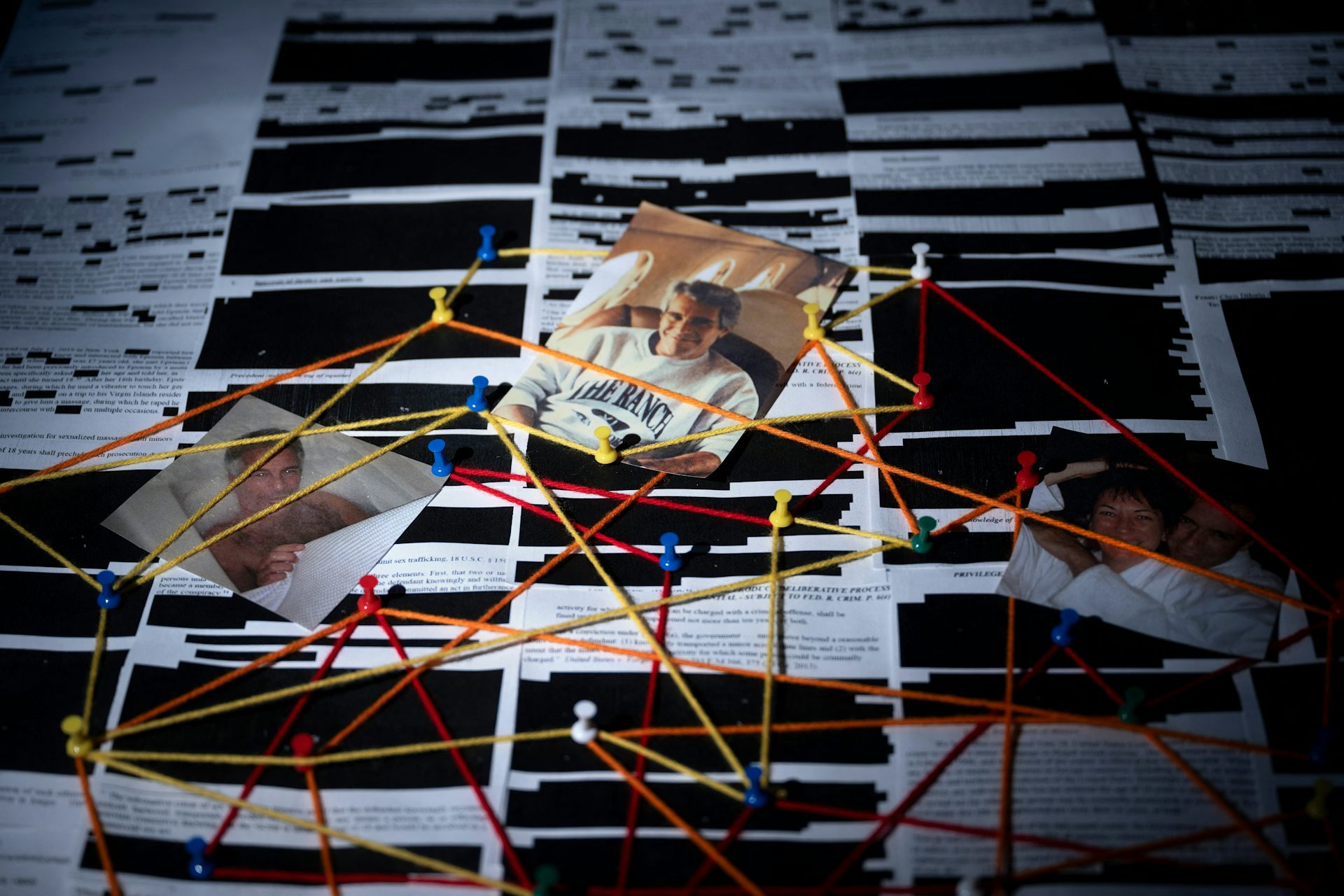

In the tumultuous aftermath of the royal murders, Gyanendra Shah – Mahendra’s second son, brother to the murdered king – succeeded to the throne.

The nation was grieving and traumatized, and people found the new King Gyanendra to be an uncharismatic monarch. An armed Maoist insurgency was threatening rural Nepal and working to capitalize on the tragedy, while the multiparty Parliament bickered in the capital. In an attempt to gain control of the situation, King Gyanendra declared a state of emergency and took direct control of the government in 2005.

The country united against him.

In spring 2006, people took to the streets for three weeks, grinding Nepal to a standstill. King Gyanendra capitulated to the insurgency.

At the time, he was so unpopular that the interim government decided to dissolve the monarchy completely. They stripped the king of all ceremonial roles and all religious activities. They wrote the king out of the national anthem and took his portrait off the national currency. They legally declared the country a secular democracy and turned the palace into a museum. The king moved out of the palace in June 2008.

The transition away from monarchy attempted to free Nepal from its history of enforced unity. The first post-monarchy Parliament featured representatives wearing all forms of clothing, taking their oaths in many different languages, tasked with writing a new, inclusive constitution. A pluralist national anthem proclaimed, “We are one Nepali garland, made of hundreds of different flowers.”

Challenges today

Unfortunately, Nepal’s post-monarchy government has struggled to live up to the hopes that swept it to power. The new constitution ran years late, while major leaders have been accused of corruption. The political parties struggle to hold coalitions together, and the constantly overturning government has seen 12 administrations in 16 years.

This instability has led some Nepalis to become nostalgic for the idea of unity through monarchy.

Today, when some people take to the streets to demand a return to Hindu kingship, many of them are not expressing love for Gyanendra Shah. The former king was not beloved; he ruled under clouds of grief and was fired before many got accustomed to his presence.

The ex-king has been living quietly in Nepal for the past 16 years. He rarely makes public appearances, though he occasionally attends religious events, and he once showed up at a nightclub. He periodically makes public statements calling for political peace and unity. While he seems to support recent rallies, he has not explicitly expressed any intention to return to power.

But as the current administration bickers, and Nepalis become ever more disillusioned with their government, I argue that the former king makes a useful tool for protest.

Anne Mocko has received research funding from the US Government through the FLAS and Fulbright Hays programs.

Read These Next

Michelangelo hated painting the Sistine Chapel – and never aspired to be a painter to begin with

A red chalk sketch for the Sistine ceiling fetched an eye-popping sum at auction, reflecting the artist’s…

Why Stephen Colbert is right about the ‘equal time’ rule, despite warnings from the FCC

The ‘equal time’ rule has been around for a century and aims to promote broadcasters’ editorial…

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…