How Indigenous peoples are reclaiming their celebrations of the summer solstice − and using them to

A historian of astronomy writes about the role of astronomical events in Indigenous cultures − and also the exploitation of their sacred traditions in present times.

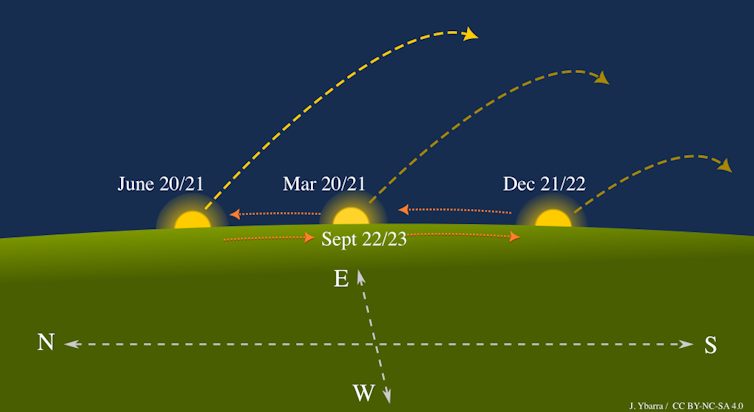

If we were to watch the Sun rise every morning, we would notice that its location appears to shift a little each day.

During springtime in the Northern Hemisphere, the Sun appears on the horizon farther north each day. Annually, around June 20 or 21, this motion appears to stop in what is known as the summer solstice. During that time, the Earth’s axis is angled toward the Sun, and the intensity of sunlight on the Northern Hemisphere is greatest.

As a historian of astronomy, I am interested in the role astronomical events had on ancient people and continue to have in modern times. My ancestors lived on the Central Mexican Plateau, where for many Indigenous cultures, both past and present, the rising and setting of the Sun during equinoxes and solstices were sacred events.

North American solstice rituals

The significance of the summer solstice to the Indigenous peoples of Mexico largely depended on regional agricultural cycles. The summer solstice was not acknowledged in the ritual calendar of the Aztecs. This may be because in the basin of Mexico the rainy season begins in early May, and there was little agricultural activity in June.

In the Sierra Madre Occidental range northwest of the basin, however, the rainy season begins in late June. The Wixárika people of the region celebrate the summer solstice with the festival of Namawita Neixa, marking the beginning of their planting season. The Wixárika are subsistence farmers who grow primarily maize, beans and squash. They are known for their annual pilgrimages into the Wirikuta desert, which they believe is the birthplace of the Sun.

For many of the Indigenous peoples of the U.S. and Canada, the summer solstice is associated with a ceremonial Sun dance. The ceremony is thought to have originated with the Sioux people and spread throughout the Great Plains in the early 19th century after being adopted by neighboring tribes.

This time period also coincided with the forced displacement of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands, resulting in extreme cultural changes, where bison hunting and communal land use were replaced with sedentary life and farming on individual plots of land.

Suppression of Indigenous culture

In 1883, the U.S. government began a campaign to suppress the Sun dances, designating them as offenses for which penalties included imprisonment. The dominant culture at the time did not consider Indigenous rituals and beliefs as genuine religion – it was thus believed that they could not be afforded the protections of the First Amendment.

In the struggle for religious freedom and to preserve their traditions, many tribal leaders presented the dances as social events and celebrations of national holidays, most notably the Fourth of July. In other tribal communities, the dances were held in secret.

It wasn’t until 1934 that the U.S. government partially reversed its policy and allowed the dance to be performed again, although still prohibiting some ritual aspects.

In 1972, almost a century after the initial suppression, the Lakota Sun Dance was held once again at the Pine Ridge Reservation in its full traditional form. Six years later, Congress passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, acknowledging the right of Native Americans to participate in traditional ceremonies, access sacred sites, and possess sacred objects.

Ritual to resistance

In modern times, Indigenous people are dealing with many other challenges that include environmental degradation and cultural appropriation.

In the Wirikuta desert of north-central Mexico, increased industrial farming has resulted in accelerated extraction of groundwater and the reduction of biodiversity. The Wixárika people are becoming increasingly concerned about the effect this is having on their traditional lifestyle.

Around the summer solstice of 2023, a special pilgrimage was made by members of a regional Wixárika council to pray for rain, protection of their sacred lands and “renewal of the world.” The region has been experiencing recent heat waves and droughts. After the ceremony, the council released a public statement in which it petitioned the Mexican government for protections for their way of life and the environment.

In the U.S., a new struggle surrounds the Sun dance: In the 1980s, nonnative entrepreneurs started the commercialization of Indigenous products and practices. This includes the organization of ceremonies and dances for profit, which are usually devoid of history and cultural context. The profits rarely trickle back into the communities, many of which struggle for basic resources. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1 in 3 Indigenous Americans live in poverty.

In response, during an international convention of Sioux people in June 1993, a unanimous Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality was passed, calling on all Indigenous peoples to resist the exploitation and abuse of their sacred traditions. This has led to limiting the participation of many Sun dances to tribal members. Today, Native Americans are still actively working to preserve their culture and spirituality.

Both the words “solstice” and “resist” derive from the Latin verb sistere, which means “to stop” or “to stand still.” Interestingly, some acts of resistance by Indigenous peoples to preserve their traditional ways of life revolve around the solstice.

The Wixárika people are asking the outside world to stop industrial practices that are damaging the environment. The Sioux are demanding a stop to the exploitation of their sacred traditions.

Jason E. Ybarra does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Algorithms that customize marketing to your phone could also influence your views on warfare

AI systems are getting good at optimizing persuasion in commerce. They are also quietly becoming tools…

How Jesse Jackson set the stage for Bernie Sanders and today’s progressives

The coalitions that Jackson built during his presidential campaigns created enduring infrastructure…

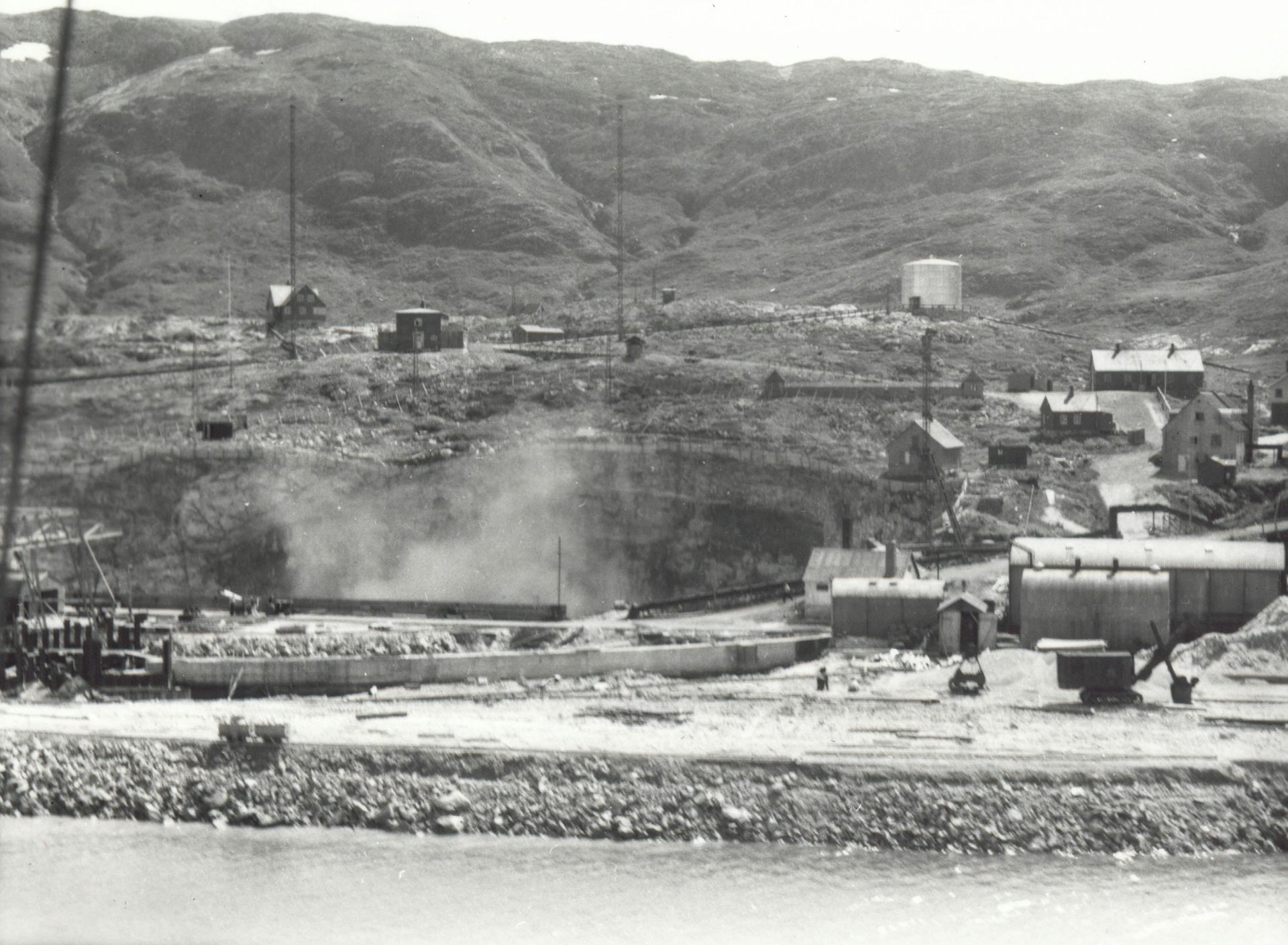

In World War II’s dog-eat-dog struggle for resources, a Greenland mine launched a new world order

Strategic resources have been central to the American-led global system for decades, as a historian…