Gender-nonconforming ancient Romans found refuge in community dedicated to goddess Cybele

In ancient Rome, male followers of the goddess Cybele, known as Galli, some of whom surgically removed their testicles, were often considered feminine.

A Vatican declaration, the “Infinite Dignity,” has brought renewed attention to how religions define and interpret gender and gender roles.

Approved by the pope on March 25, 2024, the Vatican declaration asserts the Vatican’s opposition to gender-affirming surgery and surrogacy. While noting that people should not be “imprisoned,” “tortured” or “killed” because of their sexual orientation, it says that “gender theory” and any sex-change intervention reject God’s plan for human life.

The Catholic Church has long emphasized traditional binary views of gender. But in many places, both present and past, individuals have been able to push back against gender norms. Even in the ancient Roman Empire, individuals could transgress traditional conceptions of gender roles in various ways. While Roman notions of femininity and masculinity were strict as regards clothing, for instance, there is evidence to suggest that individuals could and did breach these norms, although they were likely to be met with ridicule or scorn.

As a scholar of Greek and Latin literature, I have studied the “Galli,” male followers of the goddess Cybele. Their appearance and behaviors, often considered feminine, were commented on extensively by Roman authors: They were said to curl their hair, smooth their legs with pumice stones and wear fine clothing. They also, but not always, surgically removed their testicles.

Cybele: Mother of the gods

In the philosophical treatise “Hymn to the Mother of the Gods,” Julian the Philosopher, the last pagan emperor of the Roman empire, writes about the history of the cult of Cybele. In this treatise, he describes the cult’s main figures and how some of its rites were performed.

Often referred to as the Mother of the Gods, Cybele was first worshiped in Anatolia. Her most famous cult site was located at Pessinous, the modern Turkish village of Ballıhisar, about 95 miles southwest of Ankara, where Julian stopped to pay a visit on his journey to Antioch in 362 C.E.

Cybele was known in Greece by around 500 B.C.E. and introduced to Rome sometime between 205 and 204 B.C.E. In Rome, where she came to be recognized as the mother of the state, her worship was incorporated into the official roster of Roman cults, and her temple was built on the Palatine, the political center of Rome.

Cybele’s cult gave rise to a group of male followers, or attendants, known as Galli. Among the surviving material evidence related to their existence are sculptures, as well as a Roman burial of an individual Gallus discovered in Northern England.

Attis: Cybele’s human companion

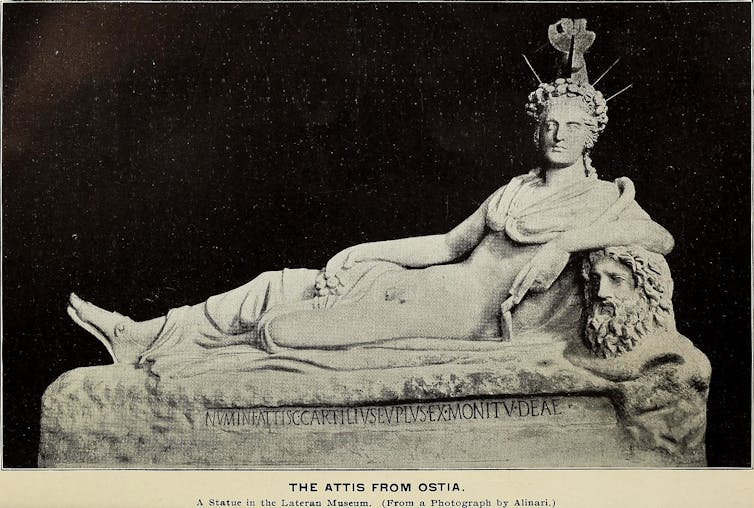

A statue from Ostia, Rome’s port city, depicts a reclining Attis, Cybele’s youthful male human companion.

What is highly unusual about this statue, which is at the Vatican museum, is how the sculptor has draped the clothing to draw attention to Attis’ groin and stomach: No discernible genitalia are visible. Attis, at first sight, appears to be a woman.

In their tellings of Cybele’s myth, Greek and Roman authors give differing versions for Attis’ self-castration. The Roman poet Catullus describes how Cybele puts Attis into a state of frenzy, during which he castrates himself. Immediately afterward, Attis is referred to by female adjectives as she calls to her companions, the Gallae, using the female form instead of the masculine Galli. Catullus’ poem highlights the ambiguity in Attis’ gender and that of Cybele’s attendants.

Material evidence for the Galli

A relief sculpture from Lanuvium, now at the Musei Capitolini in Rome and dated to the second century C.E, is one of the few surviving representations of a Gallus.

This individual is surrounded by objects commonly associated with Cybele’s cult, including musical instruments, a box for cult objects and a whip. The sculpted figure is adorned with an elaborate headdress or crown, a torque necklace and a small breastplate, as well as ornate clothing.

Other than signaling the person’s connection to Cybele’s cult, the objects and adornments also suggest that the person’s gender identity is somewhat ambiguous, since Roman men shunned flamboyance and ornaments.

At Cataractonium, a Roman fort in Northern England, a skeleton was uncovered in the necropolis of Bainesse during excavations in 1981-82. Based on the accompanying burial goods, which included a torque anklet, bracelets and a necklace made of a type of gemstone that has been dated to around the third century C.E., archaeologists thought that these were the remains of a woman.

An examination of the bones, however, revealed that the remains were those of a young man – likely in his early twenties. Since Roman men typically did not wear the kind of jewelry found in the grave, archaeologists concluded that the individual may have been a Gallus.

Respect for Galli

Galli were attached to temples, where they formed a community. During processions in Cybele’s honor, they would follow behind the cult image and priests, chanting alongside musical instruments they played.

In Rome, they had permission to seek alms from the populace; they would also offer prophetic readings or ecstatic dances in return for payment. It is possible that they enhanced their looks in order to get more money.

Some scholars have argued that their feminine appearance was a way to differentiate themselves from the general public; likewise, that their voluntary castration signaled their renunciation of the world and devotion to Cybele, in imitation of Attis, her companion.

However, it does not seem out of the ordinary to think that some Galli were drawn to Cybele’s cult because it offered them a way to escape the strict binary gender system of the Romans. Galli, unlike other men in Rome or its empire, were able to openly present themselves or live as women, regardless of their assigned sex or how they identified.

Catullus’ poem and comments by other authors indicate that they perceived the gender of the Galli as differing from Roman concepts of masculinity. However, the Galli were also, reluctantly, respected for the role they played in Cybele’s cult. It is thus hard to know who exactly joined their communities and how they saw themselves, and whether the sources describe them accurately.

It is tempting to see the Galli as nonbinary or transgender individuals, even though the Romans did not know or use concepts such as nonbinary or transgender. Still, it is not inconceivable that a number of individuals found in the Galli both a community and an identity that allowed them to express themselves in a way that traditional Roman manhood did not permit.

The Vatican declaration asserts that the female and male binary is fixed and suggests that gender-affirming care “risks threatening the unique dignity the person has received from the moment of conception.”

Nonetheless, the existence of trans people today, as well as people who defied gender binaries in the past – including the Galli of ancient Rome – shows that it is and was possible to live outside prevailing gender norms. In my view, that makes it clear that it is unjust to impose moral teachings or judgments on how people experience their bodies or themselves.

Tina Chronopoulos does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

After a 32-hour shift in Pittsburgh, I realized EMTs should be napping on the job

A paramedic and university professor shares data about how strategic napping could help his own health…

How Dracula became a red-hot lover

Count Dracula was originally a rank-breathed predator. His transformation into a tragic romantic mirrors…