France’s biggest Muslim school went from accolades to defunding – showing a key paradox in how the c

Some of the measures the French government has taken to fight radicalization can do the opposite, three social scientists argue.

France is famously strict on enforcing what it calls “laïcité”: keeping religion out of the public sphere. Yet more than 7,500 private schools receive government funding, and most are Catholic. In a country where about 1 in 10 people are Muslim, just three Muslim high schools receive state support – or did.

In December 2023, local authorities of the French Ministry of the Interior confirmed a decision to revoke state funding from Lycée Averroès, France’s largest and most acclaimed private Muslim high school. Authorities cited “serious breaches of the fundamental principles of the Republic,” raised concerns over certain texts in religious education classes, and accused administrators of opaque financial management, among various alleged infractions.

None of these claims are supported by previous inspection reports, and many French scholars and activists have denounced the decision as politically motivated, setting off a political firestorm.

Lycée Averroès, located in the suburbs of Lille, opened in 2003 and was granted state funding in 2008. In 2013, it was named the best high school in France, according to the Parisien newspaper’s rankings, and has consistently ranked among the region’s best in recent years. Teachers and administrators pride themselves on being dedicated to both French Republican and Islamic values. As our research has shown, the school often goes above and beyond to teach civic values such as equality and laïcité.

In many French Muslim communities, the school is seen as a beacon – an example of a Muslim institution that succeeded despite discrimination, political tensions around Islam, and the French Republic’s strict secularism.

The defunding decision represents a common paradox in contemporary France: Many of the steps its government takes to supposedly protect “French Republican values,” better “integrate” Muslim minorities or prevent radicalization have the potential to do the opposite.

High scores, high scrutiny

Private schools in France can receive state funding for up to about three-quarters of their operating budgets if they agree to certain stipulations. Teachers can provide optional religious education, but otherwise must follow the national curriculum and admit students of any religious background, based on merit alone.

The first Muslim schools opened in 2001, and dozens more have been established since. But as the first one to be granted state funding, Averroès has been under particularly close scrutiny since its inception. The school has previously faced controversies related to funding it received from an organization in Qatar, and a former teacher’s claims, made a decade ago, that Averroès was teaching “Islamism.”

According to an official 2020 report, from 2015 through 2020 Averroès was inspected 13 times, making it “the most inspected school” in the region. Notably, it stated that “nothing in the observations … allows (us) to think teaching practices don’t respect republican values.”

Several public figures have argued that the decision to defund Averroès is representative of “inequitable and disproportionate” treatment that French Muslims often face compared to their non-Muslim peers. As our research has shown, many Muslim schools undergo more surveillance and criticism compared to their Catholic and Jewish counterparts.

These double standards largely stem from a political environment rife with fears over Islamic extremism after numerous high-profile attacks on French soil.

However, policies intended to save French Muslim youth from radicalization can have an adverse effect, making young Muslims feel that they are not seen as fully French, and further alienating them.

For some, this sense of unequal treatment manifests in frequent protests and other demands for justice. But it has sometimes fueled riots, vandalism and social unrest.

Security and separatism

Other policies that affect education and were made in the name of French secularism have also drawn controversy for potentially discriminating against Islam.

For example, a broad 2021 measure often referred to as the “separatism law” aimed to combat perceived nonallegiance to French values. Among many requirements, the law made independent schools harder to open and easier for the state to close.

Although the text of the law does not explicitly mention Muslims, the political discourse surrounding the law clearly targeted Islam. In an October 2020 speech defending the legislation, President Emmanuel Macron stated, “What we must tackle is Islamist separatism,” which he accused of “repeated deviations from the Republic’s values.”

Yet there is little evidence of such alleged “separatism.” Rather, studies have consistently shown that Muslim support for French institutions mirrors that of the larger population.

Other examples of policies that purport to rein in radicalization, but may further fuel Muslims’ isolation, include the 2023 ban on abayas in public schools and the 2004 “headscarf” law that banned “ostentatious” religious symbols from public schools.

One study argues the 2004 ban harmed Muslim girls’ graduation rates, subsequently affecting their employment opportunities. Similarly, the abaya ban has been criticized by human rights activists, the United Nations and the U.S. Commission for Religious Freedom for unduly restricting freedom of religious expression and potentially fueling discrimination.

The future of pluralism

Based on our fieldwork, we believe France’s Muslim schools may help reduce radicalization and one of its causes: young people’s sense that being both fully French and fully Muslim is incompatible.

As one young French Muslim told us, “I’ve always been made to feel as though I’m not ‘une vraie française’ (a real French person).” Such “everyday exclusion” can fuel alienation, resentment or even emmigration.

Institutions like Averroès, however, offer a haven from the discrimination students may experience in public schools, and create a space for pupils who want to wear a headscarf or abaya. In addition, they actively denounce terrorism and radicalization.

But recent actions suggest that the French government may have lost confidence in Muslim institutions as a way to foster French values. France shut down 672 Muslim establishments between 2018 and 2021, including mosques and independent Muslim schools.

Most immediately, the decision to defund Averroès will impact its students and staff. The school offers scholarships to approximately 62% of its student body, including its nonstate-funded middle school – a number which will likely prove untenable without funding.

More broadly, such steps may intensify challenges to French Muslims’ sense of value and belonging, obstructing the path toward peaceful pluralism and paradoxically increasing the risk of radicalization and separatism.

Yet we believe there is a third risk, as well. The French Republic considers secular neutrality and equality core pillars of French identity, but many critics view its policies on Islam as prime examples of inequality and bias. Such discord may undermine these values’ legitimacy, if not their very essence.

Vincent Geisser is affiliated with organization President of the Center for Information and Studies on International Migration (CIEMI, Paris)

Carol Ferrara and Françoise Lorcerie do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

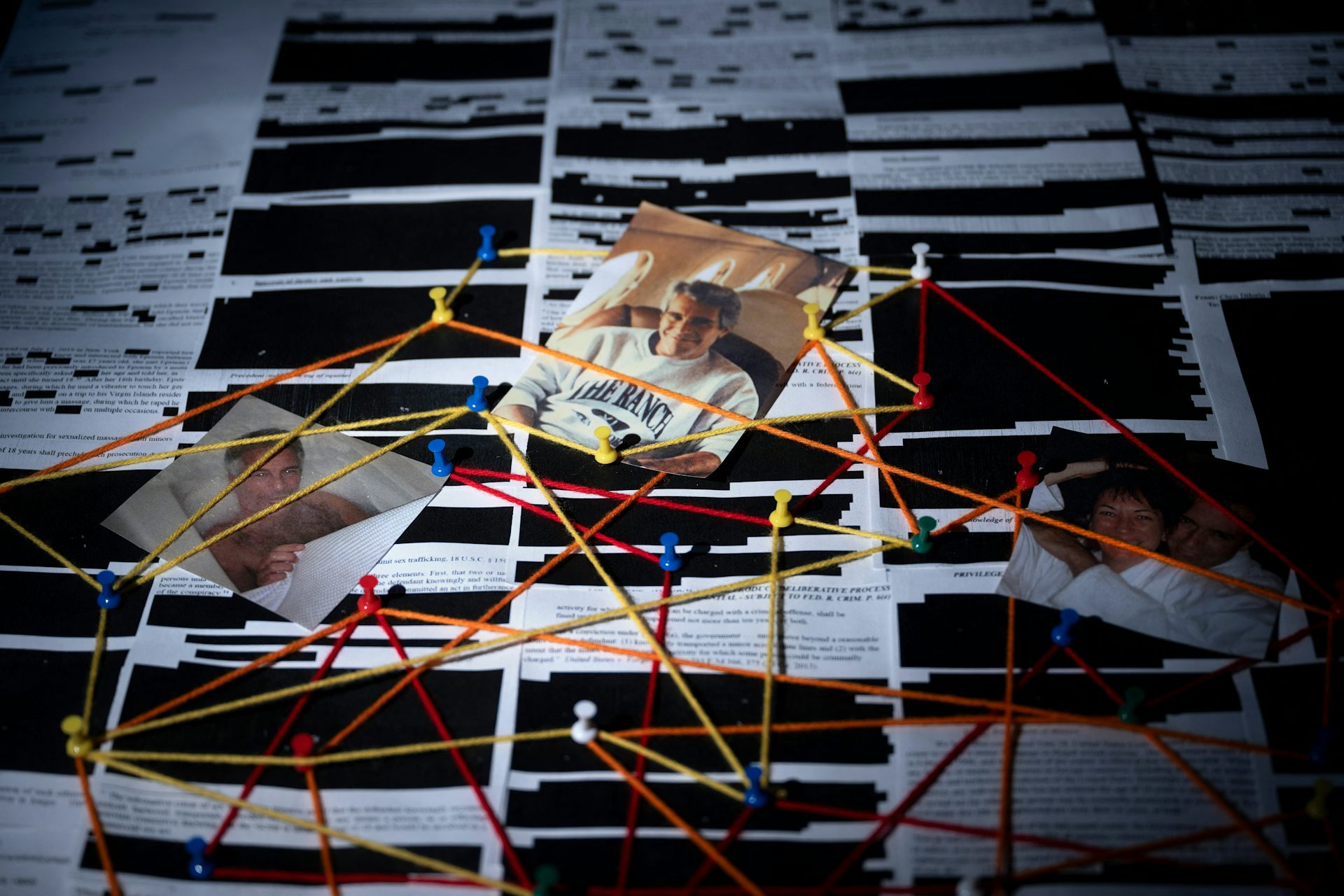

Individual donors provide only a small slice of university research funding – but Jeffrey Epstein’s

A small portion of university research funding comes from individual donors. Most universities have…

Why Michelangelo’s ‘Last Judgment’ endures

The artist used daring imagery that sparked controversy from the moment it was unveiled.

‘Learning to be humble meant taming my need to stand out from the group’ – a humility scholar explai

Humility is a virtue that many people admire but far fewer practice. A scholar describes how a professional…