How a growing number of Muslim women clerics are challenging traditional narratives

There isn't just one single narrative in Islam. Indonesia and China have a long tradition of women religious leaders – a trend that is catching up in other Muslim majority countries as well.

Recent terrorist attacks such as the one in London inevitably lead to coverage of Islamist ideology, Muslim culture and Muslim women’s rights. What is often missing, however, in my view is the fact that within Islam there are many diverse views – change is afoot and not least among women.

Indonesia recently hosted an unusual conference of Muslim women religious scholars that attracted hundreds of participants from across Indonesia as well as from countries such as Kenya, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. This International Forum of Women Ulamas (Muslim religious scholars) concluded by issuing fatwas, or nonbinding religious edicts, against child marriage, sexual abuse and environmental destruction.

It is believed to be the first-ever such gathering of Muslim women ulamas. Women have long been sidelined from the teaching and interpretation of Islam. But today, in many countries, women ulamas are emerging and acquiring more significant roles.

Indonesia’s women ulamas

In researching my book, “Mobilizing Piety,” which looked at Islam and feminism in Indonesia, I met many Muslim women who are scholars, teachers and leaders of their religion. They are not alone. There are a growing number of women ulamas around the globe. But Indonesia, with the world’s largest Muslim population, has an unusually long tradition of women ulamas.

Different from the Christian idea of priest or minister, the word ulama simply means a person who is learned in Islam. This can be a religious teacher or theologian, a judge in a religious court, a professor or a government religious official.

By this broad definition, women ulamas in Indonesia go back to the 17th century. Queen Tajul Alam Safiatuddin Syah ruled over the Islamic kingdom of Aceh (now Indonesia’s northernmost province) for 35 years and commissioned several important books of Islamic commentaries and theology. At a time when female rulers anywhere in the world were unusual, she was the primary upholder of religious authority in what was then a prosperous and peaceful kingdom.

A more recent example is that of Rasuna Said, who started as a teacher in 1923 at one of the first Islamic girls’ schools in West Sumatra. By the 1930s, she had become an important figure in the independence movement against the Dutch. After Indonesia achieved independence in 1945, Rasuna represented women’s groups in the new government. Later she served as a member of an advisory council to then-President Sukarno.

Today in Indonesia, women ulamas are helping to change how Islam is understood and practiced. Over the last three decades a new generation of women religious leaders has emerged in Indonesia, though it is not known just how many there are.

As I found in my research, Indonesian women’s rights activists are working together with women ulamas as well as progressive male ulamas who popularize alternative interpretations of the Quran that are empowering for women. For example, while some Muslims believe that the Quran allows husbands to strike wives who are disobedient, many activists counter this interpretation and point to other equally important verses that stress mutual respect and kindness between spouses.

Such a strategy has also been used by Muslim women activists in Iran and Malaysia, and is a focus of a global Muslim women’s network, which works for Muslim women’s equality. In many Muslim countries, women’s rights activists lack religious credentials. Indonesian women ulamas are more accepted as they are trained in Muslim schools and Islamic universities.

Increasing number of women ulamas

Aside from Indonesia, there are many other countries where women have begun to play a role as ulamas. Women prayer leaders (imams), however, remain rare. Many Muslims in Indonesia and elsewhere believe that women can be prayer leaders only to all-female congregations. Women-only mosques are still unusual, as in most Muslim societies, women pray at home or in a special section of the mosque. The only place with a long tradition of Muslim women who lead prayers is China.

Among China’s 21 million Muslims, women-led mosques and Quranic schools go back to at least the 19th century. The phenomenon has apparently spread in recent years as the government has loosened some restrictions on religion.

In other countries, governments have established programs to train women ulamas – and imams – as a strategy to counter the growth of extremism.

For example, in Egypt, the Religious Endowments Ministry plans to appoint 144 female imams for the first time so as to teach women about Islam and stop them from being radicalized. And in 2006, Morocco introduced the “murshidat” – Muslim women religious leaders – who now number over 400. In Turkey, as part of its effort to spread Islam more widely, the government has increased the number of official Muslim female preachers, who currently number over 700.

In Europe and North America, women have recently begun to lead prayers at several mosques. Most of these mosques are for women, but more controversially, Muslim feminist and scholar Amina Wadud has led prayer services for mixed congregations. in New York City and London.

Struggles over women’s religious authority

These are major changes, and not all Muslims agree with them.

As scholar Kathryn Robinson points out, some conservatives argue that only men should be religious leaders. Indeed, some of the attendees at the Indonesian conference were reluctant to consider themselves ulama because they see it as a masculine role. Also the issuing of fatwas by the conference of women clerics is unusual.

The conference comes at an important time, when the voices of religious conservatives and extremists, whose adherents also include women, seem to be dominant in many Muslim societies. For example, since Indonesia democratized after 1998, conservative interpretations of Islamic law have placed restrictions on women’s mobility and autonomy in some regions of the country. The recent conference’s fatwa against child marriage is especially significant because the percentage of women married before age 18 remains stubbornly high in Indonesia, with some religious leaders supporting early marriage. The same is true in other Muslim majority countries such as Egypt, where an estimated 17 percent of girls are married before their 18th birthdays.

Against such trends, the meeting of women ulamas shows a multifaceted Islam in which Muslim women clerics are asserting their rights and promoting social justice.

Rachel Rinaldo has studied two of the organizations mentioned in this article -- Rahima and Fatayat -- and written about them in her book. The research for my book (linked to in the article) was funded by a Fulbright-Hays fellowship and a Dissertation Improvement grant from the National Science Foundation.

Read These Next

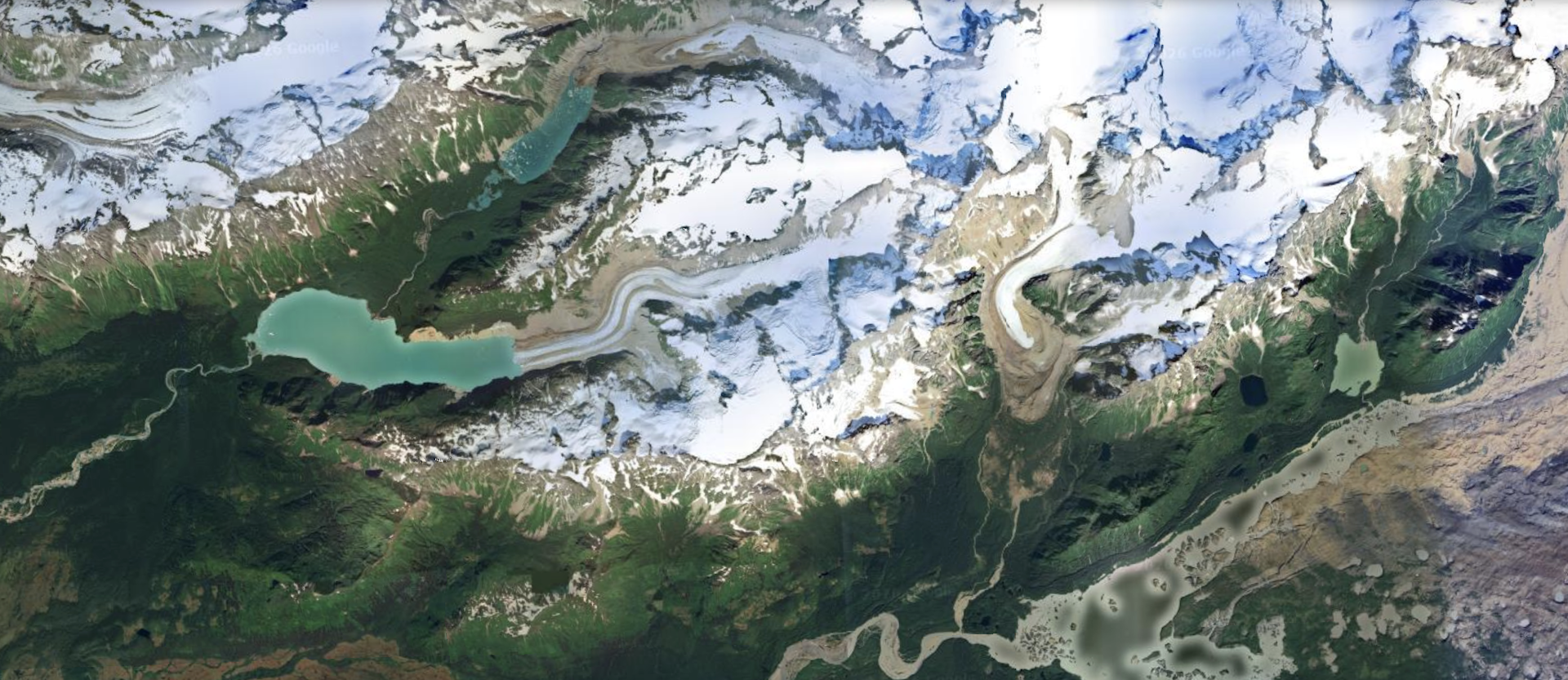

Alaska’s glacial lakes are expanding, increasing the risk of destructive outburst floods

Scientists mapped the evolution of 140 glacial lakes in Alaska and found a way to tell how much larger…

Mobile clinics offer a practical way to improve health care access in maternity care deserts

Mobile health clinics are a practical but underused solution to the growing number of maternity care…

What James Madison can teach Americans about religious freedom today

For Madison, religious freedom was not a tool for political domination. Rather, he saw it as a constitutional…