How Lourdes became a byword for hope

St. Bernadette’s visions of the Virgin Mary in the 19th century inspired the pilgrimage site millions of Catholics flock to each year.

Thousands of apparitions of the Virgin Mary have been reported by Christians across the world, from fourth-century Asia Minor, which is now Turkey, to contemporary California. Of all of these, the most renowned are the visions of Our Lady of Lourdes, reported in the mid-19th century by a teenage girl in the French Pyrenees mountains.

Ever since, devotion to Our Lady of Lourdes has gripped the Catholic imagination. Lourdes is one of the very few apparitions the Vatican has officially commended as worthy of belief, with its own feast day, Feb. 11, in the church’s annual liturgical calendar.

Some 6 million pilgrims come to the shrine in Lourdes, France, each year to pray and seek healing.

This popular pilgrimage is one of the most visible examples of the devotion of many Catholics to Mary. I am a Jesuit priest and theologian whose research focuses on Mariology, the academic study of ideas about Mary in Christian history.

The Lady in the Grotto

In 1858, a 14-year-old girl named Bernadette Soubirous reported having 18 visions of a beautiful “young lady” in a cave near Lourdes, which was then a provincial town. Soubirous said that the figure identified herself as “the Immaculate Conception” and instructed the girl to dig into the earth and drink the water she found there. In other messages, the lady asked for a church to be built there so priests could come in procession.

Reports of the events drew large crowds who believed them to be apparitions of the Virgin Mary, and many people began attributing healing properties to the waters of the spring. These extraordinary events soon attracted the notice of the Parisian press and gained the support of the French imperial court.

Many Catholics interpreted the apparitions as confirming the doctrine of Immaculate Conception, which Pope Pius IX in 1854 had declared to be an essential element of Catholic faith. This teaching holds that Mary, as the mother of Jesus, was conceived without original sin – the incomplete union with God that, according to Catholic belief, all people are born with as a result of Adam and Eve’s disobeying God in the Garden of Eden.

Church officials were quickly alerted to Soubirous’ experiences and were initially concerned about the truth of her account. After investigating, the local bishop became convinced that Mary had indeed appeared to the young woman. Popes later encouraged veneration at Lourdes, and in 1933, Soubirous herself was canonized as St. Bernadette.

Catholic churches, schools and hospitals soon began to be dedicated to Our Lady of Lourdes, and replicas of the cave, or “grotto,” are today found throughout the world. These sites are built for worshippers who cannot make the pilgrimage but who seek to share in the experience of Lourdes.

Lourdes water

Researching popular Catholic devotions has taught me that apparitions attract skeptics as easily as they do crowds of enthusiastic believers. They also stir up religious and political controversy.

From the start, church officials at Lourdes sought to deny claims of direct supernatural intervention for cures that could be scientifically explained instead. Today physicians at the International Medical Committee of Lourdes run a rigorous process of investigating claims of miraculous healings there.

Most reported healings turn out to have purely natural causes, but if the committee does not find a medical explanation, it refers the case to the local bishop for investigation. Since the 1860s, church officials have formally declared 70 of the Lourdes healings to be miracles. The most recent case, which they confirmed in 2018, involved the healing of a French nun who had been using a wheelchair and suffering severe pain for almost 30 years, but recovered soon after her pilgrimage to the grotto.

Over the course of the 20th century, the number of new miracles confirmed in Lourdes has gradually slowed because of growth in scientific understanding.

In 2006, church officials declared that, beyond “miracles,” they would recognize three additional categories of healing at Lourdes, in light of advances in medical knowledge: “unexpected,” “confirmed” or “exceptional” healings. The new categories relax the previous strict division between “natural” and “supernatural” healings, with the implication that God intervenes in many cases in which health is restored, even those that do not strictly qualify as “miracles” in the sense traditionally used by the Catholic Church.

Devotion goes digital

If the number of officially recognized miracles has declined, grassroots faith in Lourdes is as strong as ever. An understanding that sickness and healing involve psychological, emotional and spiritual aspects as well as physical ones helps explain some of Lourdes’ continuing appeal for many contemporary Catholics.

Devotional practices involve the sensory experiences of seeing, touching, tasting and hearing. Visitors travel from all over the world to light candles in the grotto, touch the rock where Soubirous said the Virgin appeared, join in the chants of the twice-daily processions, attend Mass, take Communion, and bathe in and drink the holy waters of the spring.

Psychologically, being in the company of large crowds of fellow believers strengthens social faith identity, as does seeing sick pilgrims treated with dignity and honor.

Many family, friends, spiritual advisers and volunteers from international Catholic organizations, such as the Order of Malta, accompany visitors too ill to travel alone. The physical work of caring for the sick affects people spiritually. I have visited Lourdes several times as both helper and chaplain and heard many confessions there. I know that many of those who volunteer their time as helpers – including people who are not practicing Catholics or even Christians – return home with deeper gratitude for their own health and a livelier faith.

For two months in 2020, the shrine at Lourdes closed for the first time in its history because of the pandemic. Since then, live-streaming of the grotto has attracted an even wider audience. Its dedicated YouTube channel and other social media are 21st-century virtual equivalents of the replica grottoes built in church grounds, schools, hospitals and homes around the world.

Skeptics will likely continue to dispute claims of miraculous healings and apparitions of the Virgin Mary. For millions, however, Lourdes will indisputably continue to be an important faith symbol of comfort and care, and a byword for healing and hope.

[More than 140,000 readers get one of The Conversation’s informative newsletters. Join the list today.]

Dorian Llywelyn does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Operational secrecy kept the US from making evacuation plans – and that means Americans in the Midea

A longtime diplomat explains how the State Department normally encourages and helps Americans to leave…

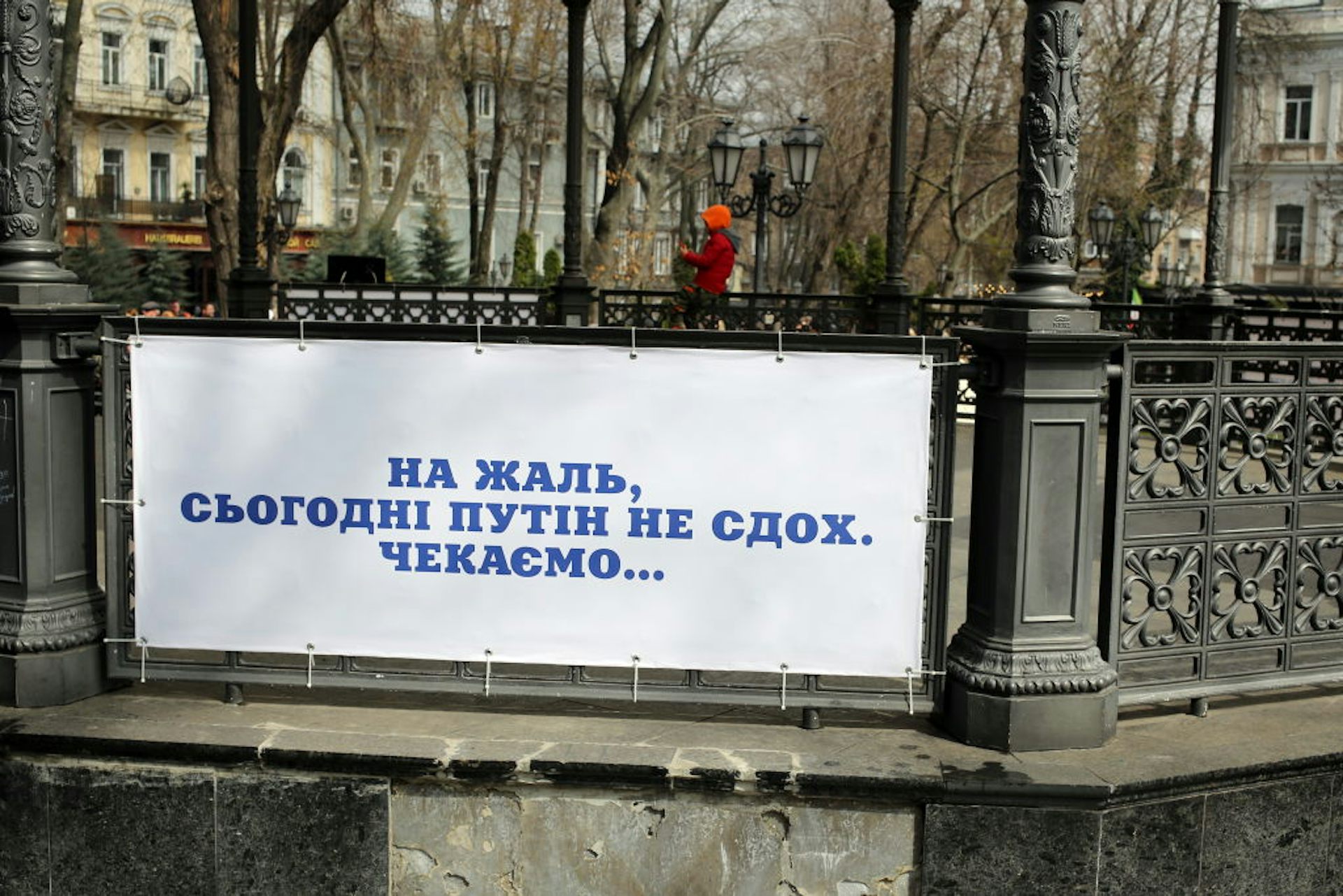

Front lines of humor: Dark humor voices Ukrainians’ hopes for victory

Humor has served many functions since Russia’s full-scale invasion, from providing Ukrainians with…

CIA agents successfully executed a plan for regime change in Iran in 1953 – but Trump hasn’t reveale

A covert US campaign in the mid-20th century helped steer Iran toward the intense anti-American sentiment…