Drink less, exercise more and take in the air – sage advice on pandemic living from a long-forgotten

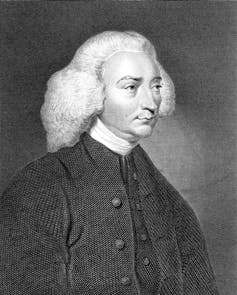

The 2,000-line poem by Scottish physician John Armstrong was written during a time of pandemic, war and increasing public disinformation. What can readers learn from it today?

A respiratory disease has spread far and wide. Conflicts at home and abroad pose dire challenges. The public is overwhelmed by questions of what to read and whom to trust as it confronts an ever more complicated world.

I am describing mid-18th century Britain. The first disease to be characterized in English as an “influenza” swept through Europe in 1743. Foreign war, as well as violent domestic struggles, had marked political life for much of the prior century and would continue for many years to come. And increasing rates of literacy and publication meant that information – good, bad and ugly – was more available than ever before.

This was the world that in 1744 saw the publication of “The Art of Preserving Health,” a long poem by the Scottish poet-physician John Armstrong that takes up a range of topics people today would refer to collectively as “wellness.” Over 2,000 lines long, the poem is divided into four books: “Air,” “Diet,” “Exercise” and “The Passions.”

During the past year and a half, many readers have turned to age-old texts to imagine new paths forward. As a teacher and scholar of 18th-century poetry, I find it useful to think about John Armstrong in this way too. So, while the world waits for vaccination rates to rise and case counts to fall, perhaps a few of this doctor’s orders are worth noting.

A prolific poet-physician

Armstrong lived and wrote in London, having moved there in the 1730s with a medical degree from the University of Edinburgh. In addition to “The Art of Preserving Health,” he wrote and translated serious medical texts, a volume of sexual health advice in verse and satirical works sending up xenophobia, superstition and medical quacks.

Of course, by the standards of modern science, even serious 18th-century medicine tends to look like quackery. For instance, no one would take mercury to cure syphilis these days – though as the historian Roy Porter put it, the general lack of good options for treatment tended to mean that the public would “try anything.” But Armstrong appears to have been especially put off by those who would prioritize profit over public health.

Immediately popular, “The Art of Preserving Health” remained in print for decades, with editions produced in London, Philadelphia, Boston and Naples, Italy. As late as 1822, a short biography of Armstrong insisted that “there is no probability that his poem will ever sink into oblivion.”

Unfortunately, that’s exactly what happened. Tastes eventually turned away from texts that seemed to combine disciplines like literature and medicine. Even John Milton’s epic poem “Paradise Lost” was criticized by some education reformers who found its incorporation of religious, historical and classical ideas to be outside the bounds of good poetry.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

Another barrier to the survival of “The Art of Preserving Health” was its language. Like many 18th-century poets, Armstrong signals his seriousness by trying to sound like both Milton and famous ancient poets like the Roman writer Virgil. This kind of writing eventually fell out of favor, and to a 21st-century ear, it can sound a little funny. For instance, when describing the discomforts of high humidity, Armstrong observes that “the spungy air/ For ever weeps” – not inaccurate, yet probably not how any serious poet would put it today. But if we let go of our modern expectations for what a poem should be or do – and perhaps keep a good dictionary close by – we find that much of Armstrong’s advice holds up.

Poetic prescriptions

First, and perhaps most relevant in the age of COVID-19, Armstrong prescribes fresh air or, in his words, a “kindly sky” in a “woodland scene where nature smiles,” away from dense crowds. This clean air, he writes, alleviates all kinds of diseases, especially respiratory infections.

Next, he’d like his readers to think about what they eat. Armstrong suggests a “watchful appetite” to help rebuild oneself from the wear and tear of everyday stresses, but he avoids naming specific foods:

I could relate ... the various powers, Of various foods: But fifty years would roll, And fifty more before the tale was done. Instead, like a modern nutritionist, he advises a keen awareness of one’s own food sensitivities, as well as a general sense of moderation.

Later, he recommends physical activity:

Begin with gentle toils; and, as your nerves Grow firm, to hardier by just steps aspire. The prudent, even in every moderate walk, At first but saunter; and by slow degrees Increase their pace. In other words, workouts should start easy and gradually ramp up. Even experienced athletes begin with a warmup, and Armstrong prescribes the same — “at first but saunter” — before kicking it into high gear.

And finally, he’d like readers to be aware of “the most important health,/ That of the mind.” His advice on drunkenness is particularly resonant in light of recent concerns about increased alcohol consumption in quarantine:

[I]t wounds you sore to recollect What follies in your loose unguarded hour Escap’d. For one irrevocable word, Perhaps that meant no harm, you lose a friend. Or in the rage of wine your hasty hand Performs a deed to haunt you to the grave. Add that your means, your health, your parts decay; Your friends avoid you; brutishly transform’d They hardly know you. That is, beware the effects of one drink too many. But Armstrong isn’t merely trying to ruin the fun. He makes lots of other suggestions about how to care for one’s emotional health. My favorite one arrives at the very end of the poem, when Armstrong prescribes a healthy dose of music:

Music exalts each Joy, allays each Grief, Expels Diseases, softens every Pain, Subdues the rage of Poison, and the Plague[.] Today, medical experts can offer more options for treatment than Armstrong ever could have imagined. But health care workers past and present will likely always have in common the challenge of keeping the public informed, engaged and well.

Melissa Schoenberger does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Why Stephen Colbert is right about the ‘equal time’ rule, despite warnings from the FCC

The ‘equal time’ rule has been around for a century and aims to promote broadcasters’ editorial…

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

How Dracula became a red-hot lover

Count Dracula was originally a rank-breathed predator. His transformation into a tragic romantic mirrors…