The history of the Taliban is crucial in understanding their success now – and also what might happe

A historian explains how the Taliban emerged out of the decades of chaos that followed the Saur Revolution in Afghanistan in 1978.

The rapid takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban left many surprised. To Ali Olomi, a historian of the Middle East and Islam at Penn State University, a key to understanding what is happening now – and what might take place next – is looking at the past and how the Taliban came to prominence. Below is an edited version of a conversation he had with editor Gemma Ware for our podcast, The Conversation Weekly.

How far back do you trace the Taliban’s origins?

While the Taliban emerged as a force in the 1990s Afghan civil war, you have to go back to the Saur Revolution of 1978 to truly understand the group, and what they’re trying to achieve.

The Saur Revolution was a turning point in the history of Afghanistan. By the mid-1970s, Afghanistan had been modernizing for decades. The two countries that were most eager to get involved in building up Afghan infrastructure were the United States and the Soviet Union – both of which hoped to have a foothold in Afghanistan to exert power over central and south Asia. As a result of the influx of foreign aid, the Afghan government became the primary employer of the country – and that led to endemic corruption, setting the stage for the revolution.

By that time, differing ideologies were fighting for ascendancy in the nation. On one end you had a group of mainly young activists, journalists, professors and military commanders influenced by Marxism. On the other end, you had Islamists beginning to emerge, who wanted to put in place a type of a Muslim Brotherhood-style Islamic state.

Daud Khan, the then-president of Afghanistan, originally allied himself with the young military commanders. But concerned over the threat of a revolutionary coup, he started to suppress certain groups. In April 1978, a coup deposed Khan. This led to the establishment of the People’s Republic of Afghanistan, headed by a Marxist-Leninist government.

How did a leftist government help ferment the Taliban?

After an initial purge of the ruling Communist Party members, the new government turned toward suppressing Islamist and other opposition groups, which led to a nascent resistance movement.

The United States saw this as an opportunity and started to funnel money to Pakistan’s intelligence services, which were allied with Islamists in Afghanistan.

At first, the United States funneled only limited funds and just gave symbolic gestures of support. But it ended up allying with an Islamist group that formed part of the growing resistance movement known as the mujahedeen, which was a loose coalition more than a unified group. Alongside the Islamist factions, there were groups led by leftists purged by the ruling government. The only thing they all had in common was opposition to the increasingly oppressive government.

This opposition intensified in 1979, when then-Afghan leader Nur Mohammad Taraki was assassinated by his second-in-command Hafizullah Amin, who took over and turned out to be a wildly repressive leader. Soviet fears of the U.S. capitalizing on the growing instability contributed to the Soviet Union invasion in 1979. This resulted in the U.S. funneling further money to the mujahedeen, who were now fighting a foreign enemy on their land.

And the Taliban emerged from this resistance movement?

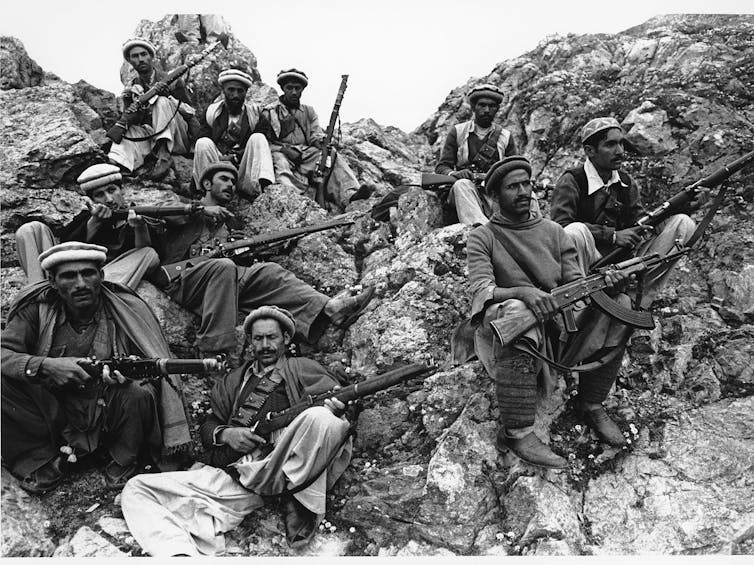

The mujahedeen waged a guerrilla-style war against Soviet forces for several years, until exhausting the invaders militarily and politically. That and international pressure brought the Soviet Union to the negotiating table.

After the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989, chaos reigned. Within three years, the new government collapsed and the old mujahedeen commanders turned into warlords – with different factions in different regions, increasingly turning on one another.

Amid this chaos, one former Islamist mujahedeen commander, Mullah Mohammad Omar, looked to Pakistan – where a generation of young Afghans had grown up in refugee camps, going to various madrassas where they were trained in a brand of strict Islamic ideology, known as Deobandi.

From these camps he drew support for what became the Taliban – “taliban” means students. The bulk of Taliban members are not from the mujahedeen; they are the next generation – and they actually ended up fighting the mujahedeen.

The Taliban continued to draw members from the refugee camps into the 1990s. Mullah Omar, from a stronghold in Kandahar, slowly took over more land in Afghanistan until the Taliban conquered Kabul in 1996 and established the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. But they never took full control of all of Afghanistan – the north remained in the hands of other groups.

[3 media outlets, 1 religion newsletter. Get stories from The Conversation, AP and RNS.]

What was behind the Taliban’s success in the 1990s?

One of the keys to the Taliban success was they offered an alternative. They said, “Look, the mujahedeen fought heroically to liberate your country but have now turned it into a war zone. We offer security, we will end the drug trade, we will end the human trafficking trade. We will end the corruption.”

What people forget is that the Taliban were seen as welcome relief for some Afghan villagers. The Taliban’s initial message of security and stability was an alternative to the chaos. And it took a year before they started to institute repressive measures such as restrictions on women and the banning of music.

The other thing that cemented their position in the 1990s was they recruited local people – through force sometimes, or bribery. In every village they entered, the Taliban added to their ranks with local people. It was really a decentralized network. Mullah Omar was ostensibly their leader, but he relied on local commanders who tapped into other factions aligned with their ideology – such as the Haqqani network, a family-based Islamist group that became crucial to the Taliban in the 2000s, when it become the de facto diplomatic arm of the Taliban by leveraging old tribal alliances in order to convince more people to join the cause.

How crucial is this history to understand what is happening now?

An understanding of what was going in the Saur Revolution, or how it led to the chaos of the 1990s and the emergence of the Taliban, is crucial to today.

Many were surprised by the quick takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban after President Biden announced a withdrawal of U.S. troops. But if you look at how the Taliban came to be a force in the 1990s, you realize they are doing the same thing now. They are saying to Afghans, “Look at the corruption, look at the violence, look at the drones that are falling from U.S. planes.” And again the Taliban are offering what they say is an alternative based on stability and security – just as they did in the 1990s. And again they are leveraging localism as a strategy.

When you understand the history of the Taliban, you can recognize these patterns – and what might happen next. At the moment, the Taliban are telling the world they will allow women to have an education and rights. They said the exact same thing in the 1990s. But like in the 1990s, their promises always have qualifiers. The last time they were in power, those promises were replaced by brutal oppression.

History isn’t just a set of dates or facts. It’s a lens of analysis that can help us understand the present and what will happen next.

Ali A. Olomi does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Why Stephen Colbert is right about the ‘equal time’ rule, despite warnings from the FCC

The ‘equal time’ rule has been around for a century and aims to promote broadcasters’ editorial…

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

Enforcing Prohibition with a massive new federal force of poorly trained agents didn’t go so well in

Both Prohibition and current mass deportation efforts were hastily built, staffed by people permitted…