Why choosing the next dalai lama will be a religious – as well as political – issue

For Tibetan Buddhists it is important that they are in charge of the selection process for the next dalai lama, but China wants to appoint its own.

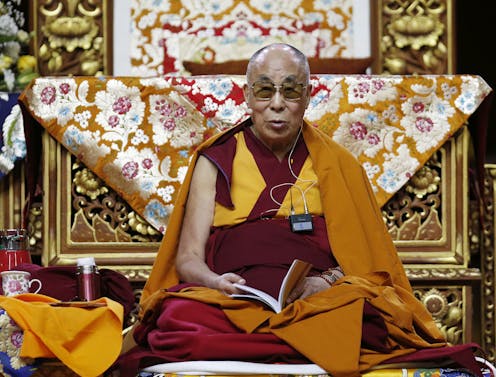

The 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, the spiritual leader of Tibet, is turning 86 on July 6, 2021. With his advancing age, the question of who will succeed him has become more pressing.

One of the most recognizable faces of Buddhism, the dalai lama is an important figure bringing Buddhist teachings to the international community.

The successor to the dalai lama is traditionally identified by senior monastic disciples, based on spiritual signs and visions. In 2011, however, the Chinese foreign ministry declared that only the government in Beijing can appoint the next dalai lama, and no recognition should be given to any other candidate.

As a scholar of transnational Buddhism, I have studied Buddhism and its refashioning in the context of globalization. The dalai lama is a highly influential figure, and choosing a successor is not just a religious issue, but a political one as well.

The dalai lamas in Tibetan Buddhism

All dalai lamas are thought to be manifestations of the bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokitesvara. Bodhisattvas are beings who work solely for the benefit of others.

For Buddhists, the ultimate goal is enlightenment, or “nirvana” – a liberation from the cycle of birth and death. East Asian and Tibetan Buddhists, as part of the Mahayana sect, believe bodhisattvas have reached this highest realization.

Furthermore, Mahayana Buddhists believe bodhisattvas choose to be reborn, to experience the pain and suffering of the world, to help other beings attain enlightenment.

Tibetan Buddhism has developed this idea of the bodhisattva further into identified lineages of rebirths called “tulkus.” Any person who is believed to be a reborn teacher, master or leader is considered a tulku. Tibetan Buddhism has hundreds if not thousands of such lineages, but the most respected and well-known is the dalai lama. The 14 generations of dalai lamas, spanning six centuries, are linked through their acts of compassion and their wish to benefit all living beings.

Locating the 14th dalai lama

The current Dalai Lama was enthroned when he was about 4 years old and was renamed Tenzin Gyatso.

The search for him began soon after the 13th Dalai Lama died. Disciples closest to the Dalai Lama set about to identify signs indicating the location of his rebirth.

There are usually predictions about where and when a dalai lama will be reborn, but further tests and signs are required to ensure the proper child is found.

In the case of the 13th Dalai Lama, after his death his body lay facing south. However, after a few days his head had tilted to the east and a fungus, viewed as unusual, appeared on the northeastern side of the shrine, where his body was kept. This was interpreted to mean that the next dalai lama could have been born somewhere in the northeastern part of Tibet.

Disciples also checked Lhamoi Latso, a lake that is traditionally used to see visions of the location of the dalai lama’s rebirth.

The district of Dokham, which is in the northeast of Tibet, matched all of these signs. A 2-year-old boy named Lhamo Dhondup was just the right age for a reincarnation of the 13th dalai lama, based on the time of his death.

When the search party consisting of the 13th dalai lama’s closest monastic attendants arrived at his house, they believed they recognized signs that confirmed that they had reached the right place.

Dalai lama memoirs

The 14th Dalai Lama recounts in his memoirs about his early life that he remembered recognizing one of the monks in the search party, even though he was dressed as a servant. To prevent any manipulation of the process, members of the search party had not shown villagers who they were.

The Dalai Lama remembered as a little boy asking for the rosary beads that monk had worn around his neck. These beads were previously owned by the 13th Dalai Lama. After this meeting, the search party came back again to test the young boy with further objects of the previous Dalai Lama. He was able to correctly choose all items, including a drum used for rituals and a walking stick.

China and dalai lama

Today the selection process for the next dalai lama remains uncertain. In 1950 China’s communist government invaded Tibet, which it insists has always belonged to China. The Dalai Lama fled in 1959 and set up a government in exile. The Dalai Lama is revered by Tibetan people, who have maintained their devotion over the past 70 years of Chinese rule.

In 1995 the Chinese government detained the Dalai Lama’s choice for the successor of the 10th Panchen Lama, named Gendun Choeki Nyima, when he was 6 years old. Since then China has refused to give details of his whereabouts. Panchen lama is the second most important tulku lineage in Tibetan Buddhism.

The Tibetan people revolted when the newly selected 11th Panchen Lama was detained. The Chinese government responded by appointing its own Panchen Lama, the son of a Chinese security officer. The panchen lamas and dalai lamas have historically played major roles in recognizing each other’s next incarnations.

China also wants to appoint its own dalai lama. But it is important to Tibetan Buddhists that they are in charge of the selection process.

Future options

Because of the threat from China, the 14th Dalai Lama has made a number of statements that would make it difficult for a Chinese-appointed 15th dalai lama to be seen as legitimate.

For example, he has stated that the institution of the dalai lama might not be needed anymore. However, he has also said it is up to the people if they want to preserve this aspect of Tibetan Buddhism and continue the dalai lama lineage. The Dalai Lama has indicated that he will decide, on turning 90 in four years’ time, whether he will be reborn.

Another option the Dalai Lama has proposed is announcing his next reincarnation before he dies. In this scenario, the Dalai Lama would transfer his spiritual realization to the successor. A third alternative Tenzin Gyatso has articulated is that if he dies outside of Tibet, and the Panchen Lama remains missing, his reincarnation would be located abroad, most likely in India. Experts believe the Chinese government’s search, however, would take place in Tibet, led by the Chinese-appointed panchen lama.

Finally, he has mentioned the possibility of being reborn as a woman – but he added in interviews in 2015 and 2019 that he would have to be a very beautiful woman. After this comment received widespread criticism in 2019, his office released a statement of apology and regret for the hurt he had caused.

[Explore the intersection of faith, politics, arts and culture. Sign up for This Week in Religion.]

The Dalai Lama is confident that no one would trust the Chinese government’s choice. The Tibetan people, as he has said, would never accept a Chinese-appointed dalai lama.

The U.S. government has expressed support for the Dalai Lama. In December 2020, the U.S. Senate passed the Tibetan Policy and Support Act, which recognizes the autonomy of the Tibetan people. The Biden administration reiterated in March 2021 that the Chinese government should have no role in the Dalai Lama’s succession.

No matter the outcome, I believe the process of finding the 15th dalai lama will certainly be different. It will likely take place outside of Tibet and under the watch of international media and a global Tibetan diaspora – with much at stake.

This is an updated version of a piece published on July 3, 2019.

Brooke Schedneck does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Do special election results spell doom for Republicans in 2026?

Special election results have anticipated recent midterm outcomes. With Democrats now overperforming,…

OpenAI has deleted the word ‘safely’ from its mission – and its new structure is a test for whether

OpenAI’s restructuring may serve as a test case for how society oversees the work of organizations…

How the 9/11 terrorist attacks shaped ICE’s immigration strategy

The growth of today’s aggressive immigration tactics traces back 25 years, when enforcement took on…