Marriage trends, political views undermining the notion of a unified American Jewish identity

The American Jewish community is changing as it becomes increasingly diverse and politically polarized.

The notion of a united Jewish American community bound together by common beliefs has been eroded by rising interfaith marriages and a growing divide between religious and nonreligious Jews.

That is one of the main themes that emerges from a recent Pew Research Center survey, the first since 2013, that provides an up-to-date portrait of the American Jewish community, including its beliefs, practices, marital patterns, racial and ethnic makeup and political views.

The American Jewish community, it found, comprises 7.5 million Jews, or 2.4% of the U.S. population. The survey headlined four central findings of special interest: American Jews are culturally engaged, increasingly diverse, politically polarized and worried about anti-Semitism.

As a scholar of American Jewish history, I was most interested in how much the survey reveals about changes in the American Jewish community.

Immigration, intermarriage and the rapid growth of Orthodox Judaism, among other phenomena, have changed the composition of the community, especially among the younger generation. Many of these changes are likely to have even greater impacts in the decades ahead.

Civil religion

Back in 1986, an insightful book titled “Sacred Survival” set forth what its author, the late social scientist and intellectual Jonathan Woocher, described as “the civil religion of American Jews.”

It was a term based upon the findings of sociologist Robert Bellah, who, in a celebrated 1967 essay, introduced the concept of “civil religion” in America. He argued that notwithstanding America’s religious diversity, a “transcendent universal religion” united the country as expressed in presidential inaugural addresses and other civic ceremonies.

Woocher made a parallel case with regard to Jews. Despite the many religious and other differences that divided American Jews from one another, there were a series of beliefs that the vast majority considered sacred and inviolable.

Among these major tenets common to religious and nonreligious Jews alike he listed “unity of the Jewish people,” “mutual responsibility,” “the centrality of the state of Israel” and “Jewish survival.” These core beliefs, he argued, bound Jews together.

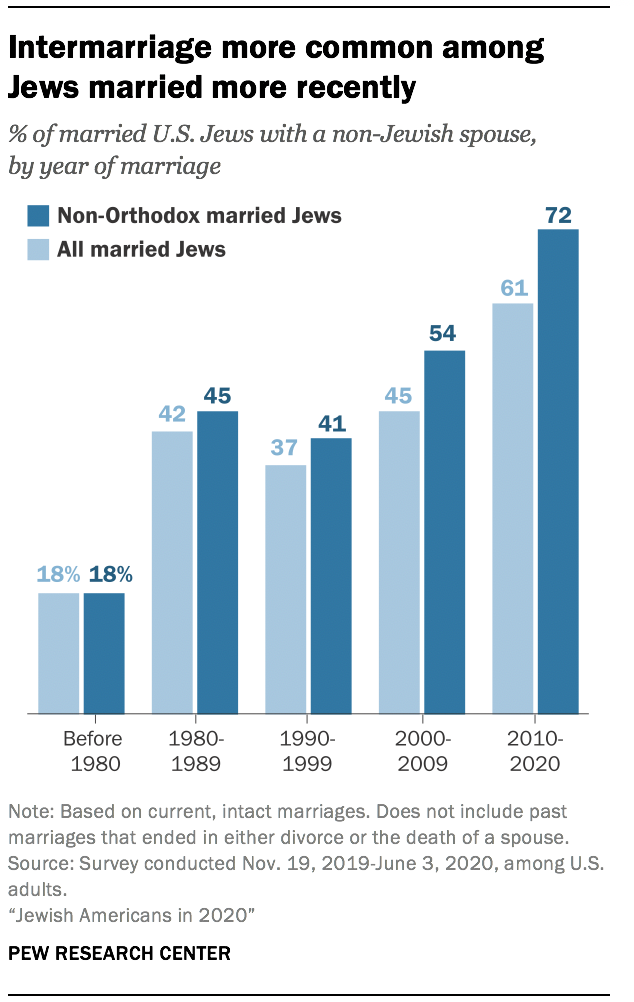

Not one of these beliefs, according to the new Pew survey, continues to unite American Jews today. Although the survey does not explain this change, it hints that intermarriage, which it defines as the presence within the Jewish community of a rising number of what it calls “non-Jewish spouses,” is a big part of the change. Fully 72% of non-Orthodox Jews who have married since 2010 describe their spouses as being “non-Jewish.”

The new Pew survey helpfully distinguishes between those who identify themselves as “Jews by religion” and those who describe themselves as “Jews of no religion,” meaning that they identify as Jews only ethnically, culturally or by family background.

A large majority – 68% – of “Jews by religion” have Jewish spouses. But an even larger majority – 79% – of “Jews of no religion,” which represents about a third of the American Jewish community, have non-Jewish spouses. Among Jews under 50, according to the survey, “two sharply divergent expressions of Jewishness appear to be gaining ground – one involving religion deeply enmeshed in every aspect of life, and the other involving little or no religion at all.”

That, I argue, helps to explain why the “civil religion” that once united American Jews has largely disappeared. The chasms illuminated by the Pew survey between religious Jews and nonreligious ones, and between Jews who have married within their faith and those who have not, increasingly divide Jews once brought together by a common set of beliefs.

Increasing divisions

Several examples highlight these chasms as well as the loss of those shared beliefs that once existed. First, Jews who married within the faith continue to uphold “the unity of the Jewish people,” much as they did in Woocher’s day – fully 95% of Orthodox Jews feel “a great deal” of a sense of belonging to the Jewish people.

By contrast, the “Jews of no religion,” and Jews who affiliate with no particular branch of Judaism – over two-thirds of whom are married to non-Jewish spouses – overwhelmingly rate their sense of belonging to a wider Jewish community in terms like “none,” “not much” or “some.”

Similarly, when asked about mutual responsibility among Jews, or, as Pew puts it, how responsible they feel “to help Jews in need around the world,” 95% of Orthodox Jews say “some” or “a great deal,” as do 87% of all Jews by religion. Among “Jews of no religion,” fewer than two-thirds feel this responsibility.

An even larger gap exists with respect to “attachment to Israel.” Orthodox and Conservative Jews overwhelmingly – about 80% – report that they feel “very” or “somewhat” attached to Israel. By contrast, a significant majority of Jews of no religion – 67% – or of no particular branch – 59% – report that they are “not too” or “not at all” attached to Israel.

These differences played out in public and on social media during the recently ended hostilities between Israel and Gaza. Although The New York Times ascribed the differences largely to age, the Pew survey suggests that the gap between religious and nonreligious Jews and between Jews who have married inside their faith and those who have not may be more significant still.

‘A Tale of Two Jewries’

The widest gap of all within the American Jewish community nowadays, according to Pew, surrounds the question of the continuation of the Jewish people – once a bedrock concern and sacred desire among American Jews of every kind.

However much Jews once disagreed internally, they all wanted their children and grandchildren to remain Jewish, in no small part a result of the trauma of losing so many Jews during the Holocaust. Now, however, those feelings seem to be ebbing.

Asked whether “it is very important that their grandchildren be Jewish,” almost all Orthodox Jews – 91% – said yes, and so did 62% of Conservative ones. By contrast, only a small percentage – 4% of Jews of no religion and 11% of Jews of no particular branch of Judaism – agreed.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

The Pew survey does not explain this overwhelming difference, but perhaps it is understandable that those with non-Jewish spouses have different expectations for their offspring than those with Jewish spouses who share their religious and cultural beliefs.

Fifteen years ago, the eminent Jewish sociologist Steven M. Cohen, based on earlier data from Jewish population studies, published “A Tale of Two Jewries,” in which he noted “sharp differences” between Jews who have married within their faith and those who have not and warned that their futures would likely be different as well.

The new Pew survey of Jewish Americans validates Cohen’s astute prophecy. By contrast, the civil religion that Woocher described as the “religious ideology … at the heart of the Jewish commitment of a significant segment of American Jewry” no longer unites Americans Jews at all.

Jonathan D. Sarna served on the advisory board for the 2013 Pew Survey of Jewish Americans.

Read These Next

Do special election results spell doom for Republicans in 2026?

Special election results have anticipated recent midterm outcomes. With Democrats now overperforming,…

The intensity and perfectionism that drive Olympic athletes also put them at high risk for eating di

Athletes in sports where weight and body image come into play, such as figure skating and wrestling,…

OpenAI has deleted the word ‘safely’ from its mission – and its new structure is a test for whether

OpenAI’s restructuring may serve as a test case for how society oversees the work of organizations…