Cities can help migrating birds on their way by planting more trees and turning lights off at night

Cities are danger zones for migrating birds, but there are ways to help feathered visitors pass through more safely

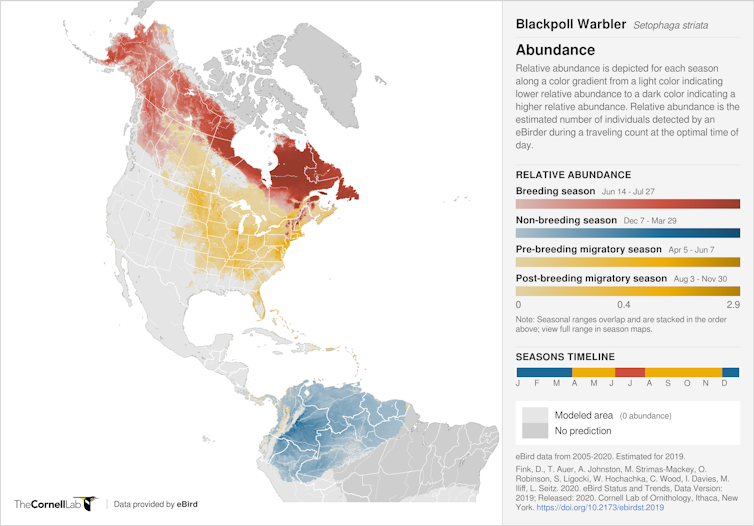

Millions of birds travel between their breeding and wintering grounds during spring and autumn migration, creating one of the greatest spectacles of the natural world. These journeys often span incredible distances. For example, the Blackpoll Warbler, which weighs less than half an ounce, may travel up to 1,500 miles between its nesting grounds in Canada and its wintering grounds in the Caribbean and South America.

For many species, these journeys take place at night, when skies typically are calmer and predators are less active. Scientists do not have a good understanding yet of how birds navigate effectively at night over long distances.

We study bird migration and how it is being affected by factors ranging from climate change to artificial light at night. In a recent study, we used millions of bird observations by citizen scientists to document the occurrence of migratory bird species in 333 U.S. cities during the winter, spring, summer and autumn.

We used this information to determine how the number of migratory bird species varies based on each city’s level of light pollution – brightening of the night sky caused by artificial light sources, such as buildings and streetlights. We also explored how species numbers vary based on the quantity of tree canopy cover and impervious surface, such as concrete and asphalt, within each city. Our findings show that cities can help migrating birds by planting more trees and reducing light pollution, especially during spring and autumn migration.

Declining bird populations

Urban areas contain numerous dangers for migratory birds. The biggest threat is the risk of colliding with buildings or communication towers. Many migratory bird populations have declined over the past 50 years, and it is possible that light pollution from cities is contributing to these losses.

Scientists widely agree that light pollution can severely disorient migratory birds and make it hard for them to navigate. Studies have shown that birds will cluster around brightly lit structures, much like insects flying around a porch light at night. Cities are the primary source of light pollution for migratory birds, and these species tend to be more abundant within cities during migration, especially in city parks.

The power of citizen science

It’s not easy to observe and document bird migration, especially for species that migrate at night. The main challenge is that many of these species are very small, which limits scientists’ ability to use electronic tracking devices.

With the growth of the internet and other information technologies, new data resources are becoming available that are making it possible to overcome some of these challenges. Citizen science initiatives in which volunteers use online portals to enter their observations of the natural world have become an important resource for researchers.

One such initiative, eBird, allows bird-watchers around the globe to share their observations from any location and time. This has produced one of the largest ecological citizen-science databases in the world. To date, eBird contains over 922 million bird observations compiled by over 617,000 participants.

Light pollution both attracts and repels migratory birds

Migratory bird species have evolved to use certain migration routes and types of habitat, such as forests, grasslands or marshes. While humans may enjoy seeing migratory birds appear in urban areas, it’s generally not good for bird populations. In addition to the many hazards that exist in urban areas, cities typically lack the food resources and cover that birds need during migration or when raising their young. As scientists, we’re concerned when we see evidence that migratory birds are being drawn away from their traditional migration routes and natural habitats.

Through our analysis of eBird data, we found that cities contained the greatest numbers of migratory bird species during spring and autumn migration. Higher levels of light pollution were associated with more species during migration – evidence that light pollution attracts migratory birds to cities across the U.S. This is cause for concern, as it shows that the influence of light pollution on migratory behavior is strong enough to increase the number of species that would normally be found in urban areas.

In contrast, we found that higher levels of light pollution were associated with fewer migratory bird species during the summer and winter. This is likely due to the scarcity of suitable habitat in cities, such as large forest patches, in combination with the adverse affects of light pollution on bird behavior and health. In addition, during these seasons, migratory birds are active only during the day and their populations are largely stationary, creating few opportunities for light pollution to attract them to urban areas.

Trees and pavement

We found that tree canopy cover was associated with more migratory bird species during spring migration and the summer. Trees provide important habitat for migratory birds during migration and the breeding season, so the presence of trees can have a strong effect on the number of migratory bird species that occur in cities.

Finally, we found that higher levels of impervious surface were associated with more migratory bird species during the winter. This result is somewhat surprising. It could be a product of the urban heat island effect – the fact that structures and paved surfaces in cities absorb and reemit more of the sun’s heat than natural surfaces. Replacing vegetation with buildings, roads and parking lots can therefore make cities significantly warmer than surrounding lands. This effect could reduce cold stress on birds and increase food resources, such as insect populations, during the winter.

Our research adds to our understanding of how conditions in cities can both help and hurt migratory bird populations. We hope that our findings will inform urban planning initiatives and strategies to reduce the harmful effects of cities on migratory birds through such measures as planting more trees and initiating lights-out programs. Efforts to make it easier for migratory birds to complete their incredible journeys will help maintain their populations into the future.

Frank La Sorte receives funding from The Wolf Creek Charitable Foundation and the National Science Foundation (DBI-1939187).

Kyle Horton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

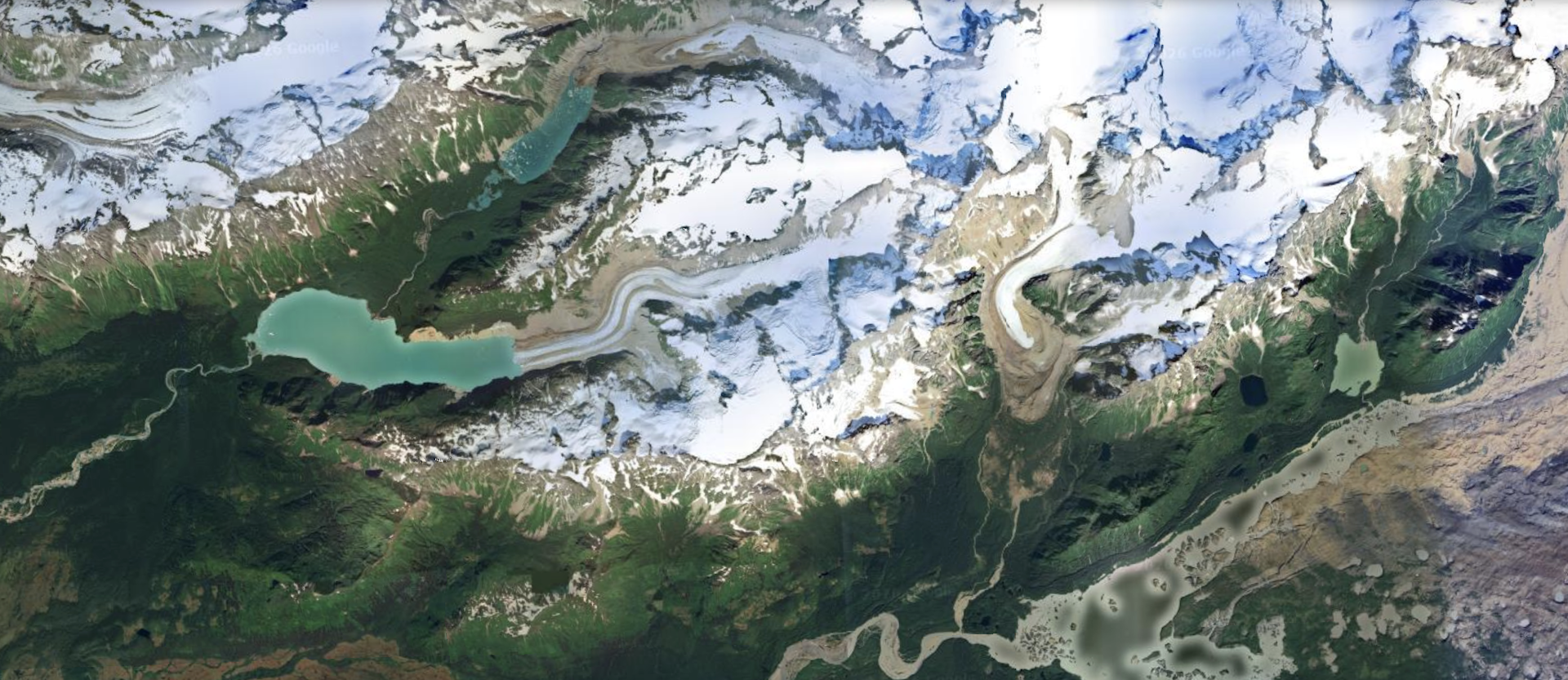

Alaska’s glacial lakes are expanding, increasing the risk of destructive outburst floods

Scientists mapped the evolution of 140 glacial lakes in Alaska and found a way to tell how much larger…

Why do mountaintops stay snowy, even though they’re closer to the Sun?

The answer has to do with the air we breathe and that bright white snowpack, as an atmospheric scientist…

Abandoned Pennsylvania mines and waste-heat recycling could make the state’s massive new data center

In Pennsylvania, new data centers could require enough electricity to power 11 million homes.