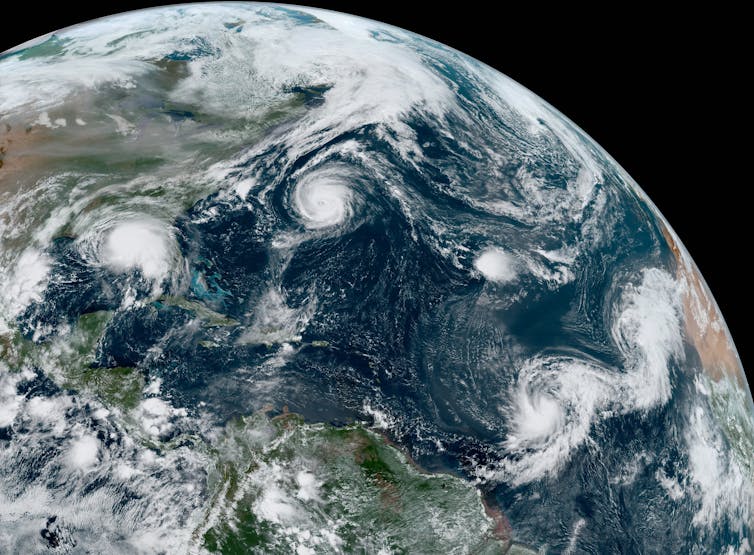

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season is so intense, it just ran out of storm names

In an unusual twist, many of those storms have been forming closer to the US coast.

Here’s how active this year’s Atlantic hurricane season has been: When Tropical Storm Wilfred formed on Sept. 18, the National Hurricane Center ran out of names for only the second time since naming began in 1950.

Even more surprising is that we reached the 21st tropical storm of the year more than two weeks earlier than the only other time this happened, in 2005.

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season is far from over. When the next tropical storm forms, forecasters will shift from the alphabetical list of people’s names to letters of the Greek alphabet – Alpha, Beta and so on. The 2005 season had six Greek-letter storms, ending with Zeta.

So, why is the Atlantic so active this year? Meteorologists like myself have been following a few important differences, including many tropical storms forming closer to the U.S. coast.

What’s causing so many tropical cyclones?

When a disturbance – a large blob of convective clouds, or thunderstorms – exists over the Atlantic Ocean, certain atmospheric conditions will help it grow into a tropical cyclone.

Warm water and lots of moisture help disturbances gain strength. Low vertical wind shear, meaning the wind speeds and directions don’t change much as you get higher in the atmosphere, is important since this shear can prevent convection from growing. And instability enables parcels of air to rise upward and keep going to build thunderstorms.

This year, sea surface temperatures have been above average across much of the Atlantic Ocean and wind shear has been below average. That means it’s been more conducive than usual to the formation of tropical cyclones.

La Niña probably also has something to do with it. La Niña is El Niño’s opposite – it happens when sea surface temperatures in the eastern and central Pacific are below average. That cooling affects weather patterns across the U.S. and elsewhere, including weakening wind shear in the Atlantic basin. NOAA determined in early September that we had entered a La Niña climate pattern. That pattern has been building up for weeks, so these trending conditions could have contributed to how favorable the Atlantic has been to tropical cyclones this year.

An unusual twist off the US coast

Four hurricanes have hit the U.S. coast this year – Hanna, Isaias, Laura and Sally, which is more than usual by this point in the hurricane season. But we also have observed many short-lived tropical storms that had less impact.

When a tropical cyclone develops from a disturbance that forms over Africa, it has a lot of ocean ahead of it to get organized and gain strength.

But this year, many storms have formed farther north, closer to the U.S. coast.

Most came from disturbances that didn’t look too promising – until they moved over the Gulf Stream. The Gulf Stream is a large ocean current that carries warm water from the Gulf of Mexico, up the East Coast and into the North Atlantic. Tropical cyclones typically need sea surface temperatures over 80 degrees Fahrenheit to form, and the warm water along the Gulf Stream can help disturbances spin up into tropical cyclones.

Because these tropical storms were already fairly far north, however, they didn’t have much time to gain strength. Meteorologists haven’t yet studied why so many storms formed this way this season, but it’s possible that it’s due to both warmer-than-normal Atlantic Ocean waters and the position of the Gulf Stream.

Lots of firsts as the season breaks records

One of the biggest surprises this year has been how consistently we have been breaking records for earliest “Nth” named storms. For example, Edouard became the earliest fifth named storm, beating 2005’s Emily by a week. Fay was the earliest sixth named storm, showing up almost two weeks earlier than Franklin did in 2005.

Wilfred was the earliest to run out the list of designated storm names. In 2005, Hurricane Wilma formed on Oct. 17, but it ended up being the year’s 22nd named storm chronologically, not the 21st like Wilfred, because an unnamed subtropical storm formed on Oct. 4. The National Hurricane Center discovered this unnamed storm during a post-season analysis.

In all, the 2005 season had 28 tropical storms. The World Meteorological Organization’s Atlantic tropical cyclone name list skips letters where easy-to-distinguish names are harder to find, like Q and Z, then moves to the Greek alphabet. The Atlantic hurricane season runs through Nov. 30. Could we run out of Greek letters? I don’t think anyone’s ready to consider that.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

Kimberly Wood receives funding from the National Science Foundation.

Read These Next

What James Madison can teach Americans about religious freedom today

For Madison, religious freedom was not a tool for political domination. Rather, he saw it as a constitutional…

Big beautiful refund? 5 tax code changes that may put more money in your pocket

Those who stand to benefit from the changes in tax code include workers who earn tips, those receiving…

Venezuela’s fragile forests face rising risks as US pushes for oil and critical minerals and illegal

The Orinoco Basin is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. It’s also rich in oil, gold…