Tomanowos, the meteorite that survived mega-floods and human folly

Tomanowos, aka the Willamette Meteorite, may be the world's most interesting rock. Its story includes catastrophic ice age floods, theft of Native American cultural heritage and plenty of human folly.

The rock with arguably the most fascinating story on Earth has an ancient name: Tomanowos. It means “the visitor from heaven” in the extinct language of Oregon’s Clackamas Indian tribe.

The Clackamas revered the Tomanowos – also known as the Willamette meteorite – believing it came to unite heaven, earth and water for their people.

Rare extraterrestrial rocks like Tomanowos have a kind of fatal attraction for us humans. When European Americans found the pockmarked, 15-ton rock near the Willamette River more than a century ago, Tomanowos went through a violent uprooting, a series of lawsuits and a period under armed guard. It’s one of the strangest rock stories I’ve come across in my years as a geoscientist. But let me start the tale from its real beginning, billions of years ago.

History of a rock

Tomanowos is a 15-ton meteorite made, as most metal meteorites are, of iron with about 8% nickel mixed in. These iron and nickel atoms were formed at the core of large stars that ended their lives in supernovae explosions.

Those massive explosions spattered outer space with the products of nuclear fusion – raw elements that then ended up in a nebula, or cloud of dust and gas.

Eventually the elements were forced together by gravity, forming the earliest planet-like orbs, or protoplanets of our solar system.

Some 4.5 billion years ago, Tomanowos was part of the core of one of these protoplanets, where heavier metals like iron and nickel accumulate.

Some time after that, this protoplanet must have collided with another planetary body, sending this meteorite and an unknowable number of other chunks back out into space.

Riding the flood

Subsequent impacts over billions of years eventually pushed Tomanowos’ orbit across that of the Earth. As a result of this cosmic billiards game, the Tomanowos meteorite entered Earth’s atmosphere around 17,000 years ago and landed on an ice cap in Canada.

Over the following decades, flowing ice slowly transported Tomanowos southwards, towards a glacier in the Fork River of Montana in what is now the United States. This glacier had created a 2,000-foot-high ice dam across the river, impounding the enormous Lake Missoula upstream.

The ice dam crumbled when Tomanowos was nearing it, releasing one of the largest floods ever documented: the Missoula Floods, which shaped the Scablands of Washington State with the power of several thousand Niagara Falls.

Trapped in ice and rafted down river by the flood, Tomanowos crossed modern-day Idaho, Washington and Oregon along the swollen Columbia River at speeds sometimes faster than 40 miles per hour, according to simulations by modern geologists. While floating near what’s now the city of Portland, the meteorite’s ice case broke apart, and Tomanowos sank to the river bottom.

It is one of hundreds of other “erratic” rocks – rocks made of elements that do not match the local geology – that have been found along the Columbia River. All are souvenirs from the cataclysmic Missoula floods, but none is as rare as Tomanowos.

A rock worth suing for

As flood waters ebbed, Tomanowos was exposed to the elements. Over thousands of years, rain mixed with iron sulfide in the meteorite. This produced sulfuric acid that gradually dissolved the exposed side of the rock, creating the cratered surface it bears today.

Several thousand years after the Missoula floods, the Clackamas arrived to Oregon and discovered the meteorite. Did they know it came from the heavens, despite the lack of a crater? The name Tomanowos, or Visitor from the Sky, suggests that they may have suspected the rock’s extraterrestrial origins.

Millennia of peaceful rest in the Willamette valley ended in 1902 when an Oregon man named Ellis Hughes secretly moved the iron rock to his own land and claimed it as his property.

Hauling a 15-ton rock on a wooden cart for nearly a mile without being noticed wasn’t easy, even in the Wild West. Hughes and his son labored for three back-breaking months. Once the meteorite was on his land, he began charging admission to view the “Willamette Meteorite.”

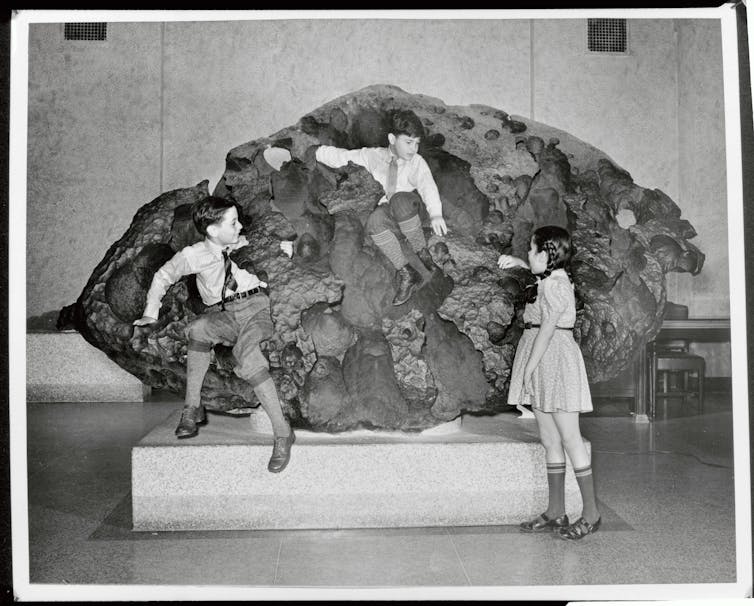

In fact, however, the legitimate owner of the iron rock turned out to be the Oregon Iron and Steel Company, which owned the land where Hughes had found the meteorite and sued for its return. While the suit worked its way through the courts, the company hired a guard who sat atop Tomanowos 24 hours a day with a loaded gun. They won the case in 1905, and sold Tomanowos to the American Museum of Natural History in New York a year later.

Floods

Today Tomanowos can be seen in the museum’s Hall of the Universe exhibition, which still refers to it as the Willamette Meteorite. In 2000 the museum signed an agreement with descendants of the Clackamas tribe, recognizing the meteorite’s spiritual significance to the Native people of Oregon.

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde hold an annual ceremonial visit with the ancient rock that, as their ancestors so aptly observed, brought the sky and the water together here on Earth. In 2019 several fragments of the meteorite that had been held separately were returned to the tribe.

But the museum’s written display tells only some of the rock’s long story. It omits the Missoula Floods, despite the significance of this event for modern earth science.

Decades after geologists J. Harlen Bretz and Joseph T. Pardee separately posited the theory of the Missoula floods in the early 20th century, their research was used to explain how Tomanowos reached Oregon, where it was found. Their work also triggered one of the most significant paradigm shifts in recent geoscience: the recognition that catastrophic flooding events significantly contribute to the erosion and evolution of landscape

Previously, scientists had followed Lyell’s principle of uniformitarianism, which held that Earth’s landscape was sculpted by regular, natural processes distributed evenly over long times. Normal floods fit into this theory, but the notion of swift, catastrophic events like the Missoula Floods were somewhat heretic.

The idea of huge Ice Age floods helped geologists a century ago prevail over pre-scientific, religious explanations for unusual finds – such as how marine fossils could be found at high elevation, and how a giant metal rock from outer space came to rest in Oregon.

Daniel Garcia-Castellanos receives funding from CSIC (Spanish Public Research Council) and the European Commission.

Read These Next

Abandoned Pennsylvania mines and waste-heat recycling could make the state’s massive new data center

In Pennsylvania, new data centers could require enough electricity to power 11 million homes.

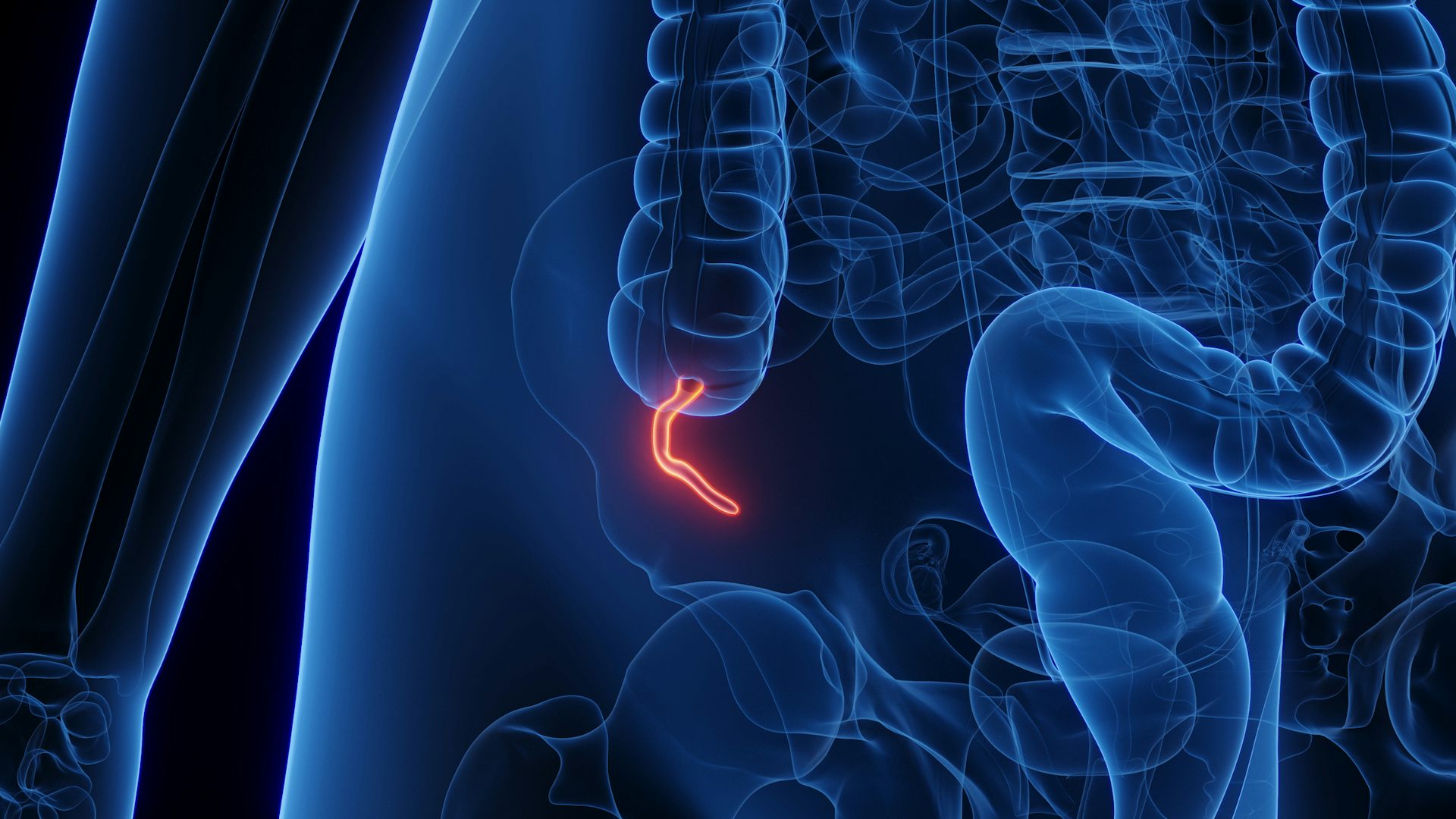

What does the appendix do? Biologists explain the complicated evolution of this inconvenient organ

The appendix has independently evolved at least 32 times across 361 mammalian species. What makes it…

I’ve studied MAGA rhetoric for a decade, and this is what I see in Hegseth’s boasts, action-movie on

Why does Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth brag and gloat in his statements about the Iran war? In the…