Tagging data show that blue sharks are true globalists

You won't see a blue shark near the beach, but thanks to 50 years of tagging data, scientists are learning about their wide-ranging lives at sea.

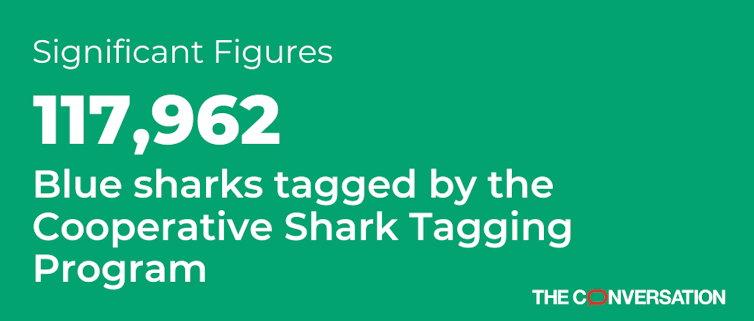

Blue sharks are among the widest-ranging shark species in the oceans. We know this partly because from 1962 to 2013, 117,962 blue sharks were tagged as part of the ongoing Cooperative Shark Tagging Program.

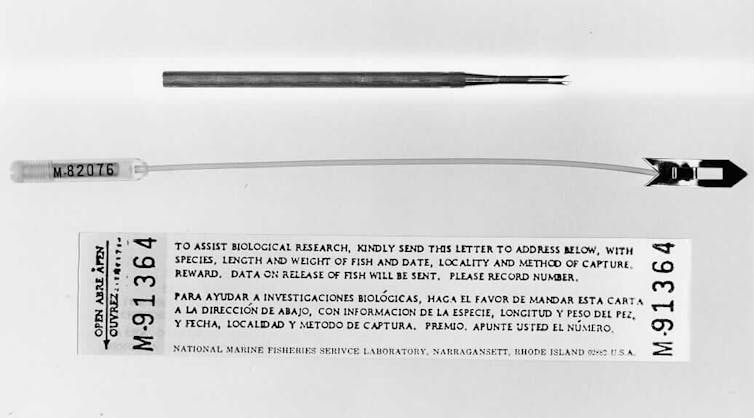

This partnership between the commercial fishing industry, the U.S. government, recreational fishermen and academic research scientists is the longest-running tagging program in the world. Since its launch in 1962, participants have tagged hundreds of thousands of sharks representing 35 different species.

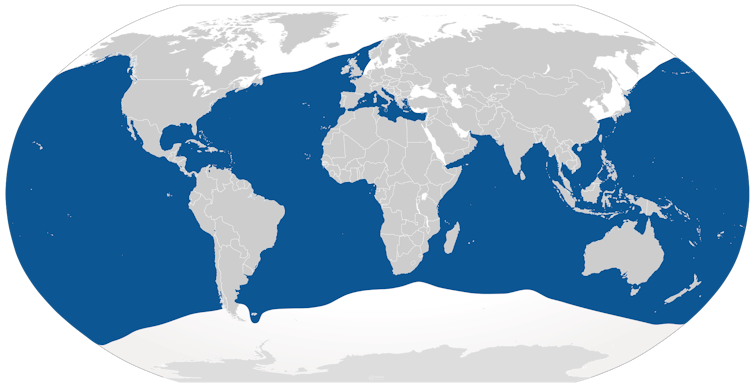

More than half (51%) of the animals tagged were blue sharks (Prionace glauca) – a total of 117,962 individual sharks. This is probably because blues are abundant: They are found in all of the world’s oceans, as far north as Alaska and as far south as Chile, but rarely venture near shore.

Unlike some other sharks, blues are not a prized commercial species, likely because most people think they taste disgusting. That makes fishermen willing to tag and release them instead of harvesting them.

But blue sharks are often caught unintentionally as bycatch along with targeted fish. They are classified as near threatened, and there is evidence that their population is decreasing.

Each tag attached to a shark carries an identification number and contact information, so that recaptures can be reported and matched to data collected during the initial tagging. The data show that these sharks really move. One traveled a record-breaking 3,997 nautical miles from waters off Long Island, New York, where it was first tagged, to the south Atlantic where it was recaptured – a distance longer than the Great Wall of China.

The sharks were caught in all seasons throughout their range, in tropical waters warmer than 68 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius) and temperate waters, which range from 50°-68°F (10°-20°C). In more tropical climates, blue sharks occupy waters as deep as 1,150 feet (350 meters), which are cooler than water near the surface. Their ability to inhabit a wide range of depths enables them to move around as seasons and water temperatures change.

Tagging data confirm that blue sharks migrate incredibly long distances, with some even crossing the equator from the North Atlantic to the South Atlantic. All of this movement allows them to mix and mingle with individuals throughout their range. This tells scientists that all blue sharks in the Atlantic Ocean are part of one mating pool, and can be considered one big population, rather than smaller separate groups.

The fact that blue sharks range so widely suggests that an event in one part of the Atlantic, such as an oil spill, could potentially affect the number of mating pairs across the population. This could reduce the number of blue sharks in the next generation and lead to a decline in their population throughout the Atlantic. It could also reduce their genetic diversity and make the survivors more prone to mortality from disease.

About 7% of the tagged blue sharks (8,213) were recaptured later, sometimes after more than a decade. One shark was recaptured nearly 16 years after it was first tagged. Scientists estimated that this shark was between 8 and 11 years old at the time it was tagged, based on its size. That original age estimate would have made the shark 24 to 27 years old when it was recaptured, which falls within the current estimated range of maximum age for the species.

Thanks to tagging data, scientists have learned a lot about the ecology of several species, including smooth dogfish and sandbar sharks. As a scientist pursuing a career in marine conservation, I look forward to more wondrous discoveries about these marvelous animals.

Jasmin Graham does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Mobile clinics offer a practical way to improve health care access in maternity care deserts

Mobile health clinics are a practical but underused solution to the growing number of maternity care…

What James Madison can teach Americans about religious freedom today

For Madison, religious freedom was not a tool for political domination. Rather, he saw it as a constitutional…

Abandoned Pennsylvania mines and waste-heat recycling could make the state’s massive new data center

In Pennsylvania, new data centers could require enough electricity to power 11 million homes.