Spring is arriving earlier across the US, and that's not always good news

Climate change has advanced the arrival of spring by as much as several weeks in some parts of the US. This can mean major crop losses and disconnects between species that need each other to thrive.

Across much of the United States, a warming climate has advanced the arrival of spring. This year is no exception. In parts of the Southeast, spring has arrived weeks earlier than normal and may turn out to be the warmest spring on record.

Apple blossoms in March and an earlier start to picnic season may seem harmless and even welcome. But the early arrival of springtime warmth has many downsides for the natural world and for humans.

Rising temperatures in the springtime signal plants and animals to come alive. Across the United States and worldwide, climate change is steadily disrupting the arrival and interactions of leaf buds, cherry blossoms, insects and more.

In my work as a plant ecologist and director of the USA National Phenology Network, I coordinate efforts to track the timing of seasonal events in plants and animals. Dramatically earlier spring activity has been documented in hundreds of species around the globe.

Lilies, blueberries, birds and more … all sped up

Records managed by the USA National Phenology Network and other organizations prove that spring has accelerated over the long term. For example, the common yellow trout lily blooms nearly a week earlier in the Appalachian Mountain region than it did 100 years ago. Blueberries in Massachusetts flower three to four weeks earlier than in the 1980s. And over a recent 12-year period, over half of 48 migratory bird species studied arrived at their breeding grounds up to nine days earlier than previously.

Warmer spring temperatures have also led beetles, moths and butterflies to emerge earlier than in recent years. Similarly, hibernating species like frogs and bears emerge from hibernation earlier in warm springs.

All species don’t respond to warming the same way. When species that depend on one another — such as pollinating insects and plants seeking pollination - don’t respond similarly to changing conditions, populations suffer.

In Japan, the spring-flowering ephemeral Corydalis ambigua produces fewer seeds than in previous decades because it now flowers earlier than when bumblebees, its primary pollinators, are active. Similarly, populations of pied flycatchers – long-distance migrating birds that still arrive at their breeding grounds at the regular time – are declining steeply, because populations of caterpillars that the flycatchers eat now peak prior to the birds’ arrival.

Warmth followed by frost can kill

Earlier springs can devastate valuable farm crops. Cherry, peach, pear, apple and plum trees blossom during early warm spells. Subsequent frost can kill the blooms, which means the trees will not produce fruit.

In March 2012, Michigan cherry blossoms opened early after temperatures climbed into the 80s. Then at least 15 frosts from late March through May destroyed 90% of the crop, causing US$200 million in damages. And in 2017, after Georgia peach trees flowered during an extremely early warm spell, frost killed up to 80% of the crop.

Early springs also affect ornamental plants and gardens. They hasten allergy symptoms and the appearance of turf pests. Popular species like tulips open up sooner than they used to a decade or more ago. In recent years, tulips have bloomed before “tulip time” festivals in Iowa, Oregon and Michigan.

Cherry trees around Washington D.C.‘s Tidal Basin bloom at dramatically different times from year to year. They are expected to bloom weeks in advance of the National Cherry Blossom Festival in the coming decades.

Springtime shifts by region

The start of spring isn’t advancing at the same rate across the United States. In a recent study with climatologist Michael Crimmins, I evaluated changes in the arrival of springtime warmth over the past 70 years.

We found that in the Northeast, warmth associated with the leading edge of springtime activity has advanced by about six days over the past 70 years. In the Southwest, the advancement has been approximately 19 days. Spring is also arriving significantly earlier in the Southern Rockies and the Pacific Northwest. In contrast, in the Southeast the timing of spring has changed little.

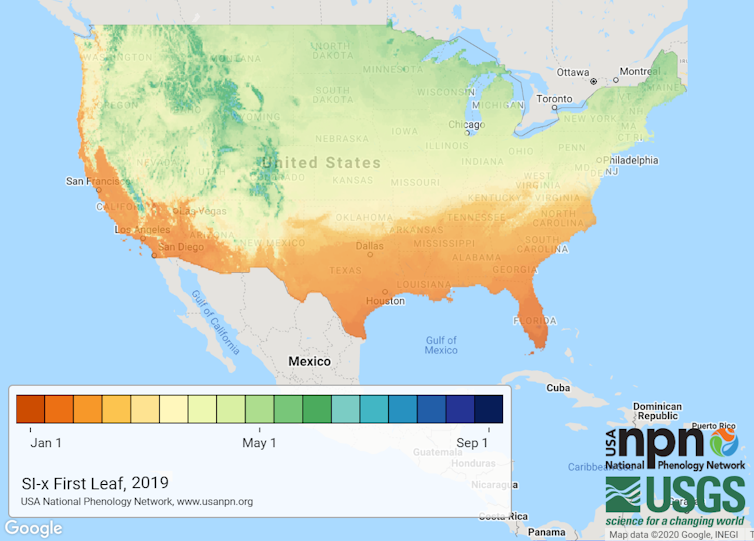

Although the trend over decades toward earlier springs is clear, weather patterns unfolding across the continent can vary the start of the season dramatically from year to year at any one spot. The USA National Phenology Network produces maps that document the onset of biological activity over the course of the spring season.

The network also maintains a live map showing where spring has arrived. In some parts of the Southeast, spring 2020 has been the earliest in decades.

Help scientists document change

While numerous studies have documented clear changes in the timing of activity in certain plants and animals, scientists have little to no information on the cycles of most of the millions of species on Earth. Nor do they know the consequences of such changes yet.

One important way to fill knowledge gaps is documenting what’s happening on the ground. The USA National Phenology Network runs a program called Nature’s Notebook suited for people of nearly all ages and skill levels to track seasonal activity in plants and animals. Since the program’s inception in 2009, participants have contributed more than 20 million records.

These data have been used in over 80 studies, and we are looking for more observations from the public that can help scientists understand what causes nature’s timing to change, and what the consequences are. We welcome new volunteers who can help us unravel these mysteries.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

The University of Arizona receives funding from the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, the National Science Foundation, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to fund the USA National Phenology Network.

Read These Next

Abandoned Pennsylvania mines and waste-heat recycling could make the state’s massive new data center

In Pennsylvania, new data centers could require enough electricity to power 11 million homes.

Silicone wristbands can help scientists track people’s exposure to pollutants like ‘forever chemical

From wearable samplers to passive environmental monitoring, new research is changing how scientists…

Today’s obsession with authenticity isn’t new – being true to yourself has troubled philosophers for

Contemporary culture seems obsessed with authenticity – but the question of how to be ‘sincere’…