Indigenous people may be the Amazon's last hope

Native Brazilians are among the Amazon's most effective defenders against logging and mining, because they're fighting not just for the environment but for their people's very survival.

Brazil’s divisive President Jair Bolsonaro has taken another step in his bold plans to develop the Amazon rainforest.

A bill he is sponsoring, now before Congress, would allow transportation infrastructure to be built on indigenous territory. Such lands cover 386,000 square miles of the Brazilian Amazon – one-fifth of the jungle. Here, Native people are constitutionally entitled to exercise sovereignty over resource use.

The right-wing Bolsonaro administration says “opening” the Amazon will boost its economy. But environmentalists, indigenous leaders and other concerned Brazilians say that the move will promote mining, logging and other damaging activities.

As evidence, they cite Bolsonaro’s appointment of a Brazilian general who last year served on the board of the Canadian mining giant Belo Sun to lead Brazil’s federal agency for indigenous peoples.

Our research on social movements in the Amazon takes us to areas affected by infrastructure development. There, we have witnessed the disheartening aftermath for Native people and met the indigenous leaders fighting to save their homelands.

Riches now in reach

The Amazon possesses a wealth of minerals including gold, diamonds, iron ore, manganese, copper, zinc and tin. But the region is so remote, with its southern edge lying 1,000 miles from Rio de Janeiro, that resource extraction was long limited by transportation costs.

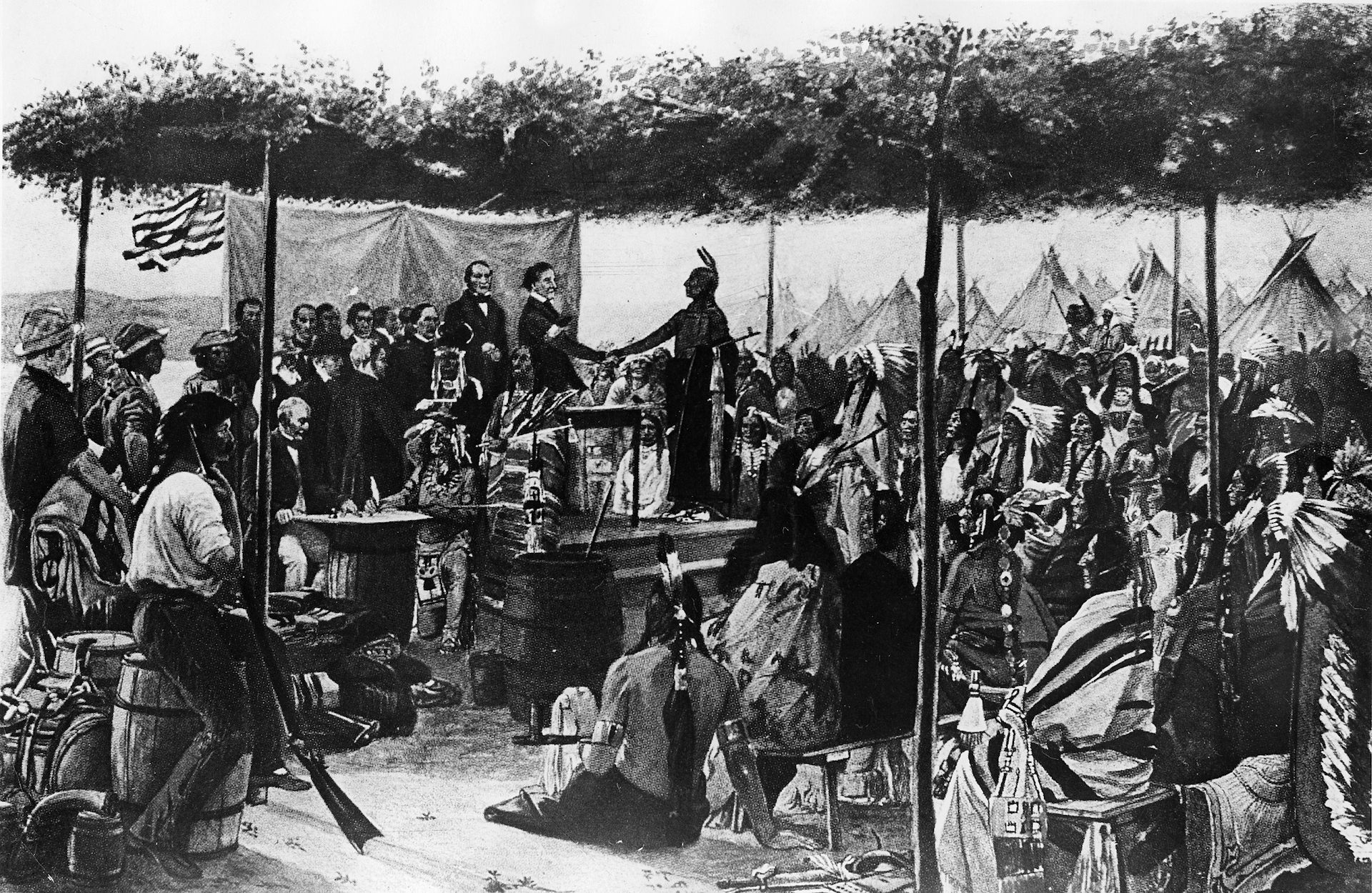

This began to change in the 1970s, when Brazil’s military government built several new highways through the Amazon. It paid little heed to the desires or safety of the 140,000 Native people living there.

Terrible abuses occurred, including the military’s systematic killing from 1967 to 1977 of up to 2,000 Waimiri-Atroari people to make way for a road to the Amazonian capital of Manaus.

The territorial aggressions culminated in the 1980s, when up to 40,000 wildcat miners invaded the Yanomami homeland looking for gold. An estimated 20% of the resident indigenous population perished from disease and violence over a seven-year period. Today there are about 900,000 indigenous people in Brazil.

After democracy was restored in 1985, Brazil got a new constitution that codified indigenous rights, including the right to aboriginal homelands. Because so much of the Amazon is indigenous territory, indigenous sovereignty became instrumental to Brazilian environmental policy.

The connection between indigenous communities and conservation is global. Indigenous people make up 5% of the world’s population, but their homelands hold 85% of its biodiversity. This can make indigenous people extremely effective environmental defenders, because in fighting for their ancestral territory they protect some of the world’s most pristine places.

A world in peril

At the turn of the millennium, Brazil was generally considered a good steward of the Amazon.

About a decade into the 21st century, however, environmental policy began to weaken to allow more infrastructure development in the Amazon. By 2016, some 34,000 square miles of the Brazilian Amazon had lost its previously protected status or seen protections reduced.

Indigenous sovereignty, however, was never called into question – until now. Since taking office in January 2019, Bolsonaro has also cut funds for the enforcement of Brazil’s strict environmental laws, leading Amazon deforestation to spike.

Brazil’s president has long seen protected indigenous land as a treasure trove of resources. In 2015 then-Congressman Bolsonaro told the newspaper Campo Grande News that “gold, tin and magnesium are in these lands, especially in the Amazon, the richest area in the world.”

“I’m not getting into this nonsense of defending land for the Indians,” he added.

Bolsonaro defends his current efforts to build in the Amazon as a means of assimilating native Brazilians so they will no longer need their territorial homelands.

“The Indian has changed, he is evolving and becoming more and more a human being like us. What we want is to integrate him into society,” he said in a video posted to social media in January.

The statement prompted a lawsuit by indigenous Brazilians accusing the president of racism, a crime in Brazil.

Resistance as conservation

Accelerating deforestation under Bolsonaro has sparked violence in the Amazon.

Seven indigenous land activists were killed in 2019, according to the Brazilian not-for-profit Pastoral Land Commission, the most in over a decade. Indigenous environmental leaders in the Colombian and Ecuadorian Amazon have also been murdered.

Such killings mostly go unsolved. But Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples Association says one indigenous activist killed in 2019, Paulo Guajajara, was gunned down by illegal loggers in November for defending Guajajara territory as part of an armed group called Guardians of the Forest.

“We are protecting our land and the life on it,” Guajajara told Reuters shortly before his murder. “We have to preserve this life for our children’s future.”

Indigenous Brazilians have also defended their land in court.

In 2012, the Munduruku sued to stop the construction of mega-dams and waterways in the Tapajós River Valley – projects that would have ended life as they know it. Federal prosecutors agreed, filing in support of the Munduruku and calling for the suspension of the largest dam’s environmental license.

Under legal pressure, the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources in their April 2016 decision curtailed the entire infrastructure plan, conserving 7% of the Amazon Basin.

Amazon’s last hope

Not every indigenous Brazilian is a born environmentalist. Many mix traditional livelihoods like hunting, fishing and gathering with agriculture and ranching.

Like other farmers who clear forest to plant more crops, indigenous farmers stand to benefit from Bolsonaro’s environmental deregulation. The president recently announced his administration would offer credit to indigenous soybean farmers who want to expand their operations.

In Roraima state, the Raposa Serra do Sol people live on land rich with gold, diamonds, copper and a slew of lesser-known metals that Bolsonaro regards as strategic to Brazil’s metallurgical economy. Royalty payments to Native peoples who open their land to miners could be substantial.

So far, however, indigenous groups are united in their resistance to federal and corporate interference. They may be the Brazilian Amazon’s last hope.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

Robert T. Walker, Aline Carrara, Cynthia Simmons, and Maira Irigaray have received funding from the Rutherford Foundation and from the US National Science Foundation.

Aline Angotti Carrara has received funding from LASPAU affiliated with Harvard University, The Rufford Foundation and from CAPES.

Cynthia S. Simmons and Maira I Irigaray do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

OpenAI has deleted the word ‘safely’ from its mission – and its new structure is a test for whether

OpenAI’s restructuring may serve as a test case for how society oversees the work of organizations…

Green or not, US energy future depends on Native nations

Native American lands contain 30% of the nation’s coal, 50% of its uranium and 20% of its natural…

What is and isn’t new about US bishops’ criticism of Trump’s foreign policy

The Catholic Church’s teachings on ‘just war’ have guided leaders’ long history of opposing…