When people downsize to tiny houses, they adopt more environmentally friendly lifestyles

Research shows that moving from a larger dwelling to a tiny home can change behavior in surprising ways.

Interest is surging in tiny homes – livable dwelling units that typically measure under 400 square feet. Much of this interest is driven by media coverage that claims that living in tiny homes is good for the planet.

It may seem intuitively obvious that downsizing to a tiny home would reduce one’s environmental impact, since it means occupying a much smaller space and consuming fewer resources. But little research has been done to actually measure how people’s environmental behaviors change when they make this drastic move.

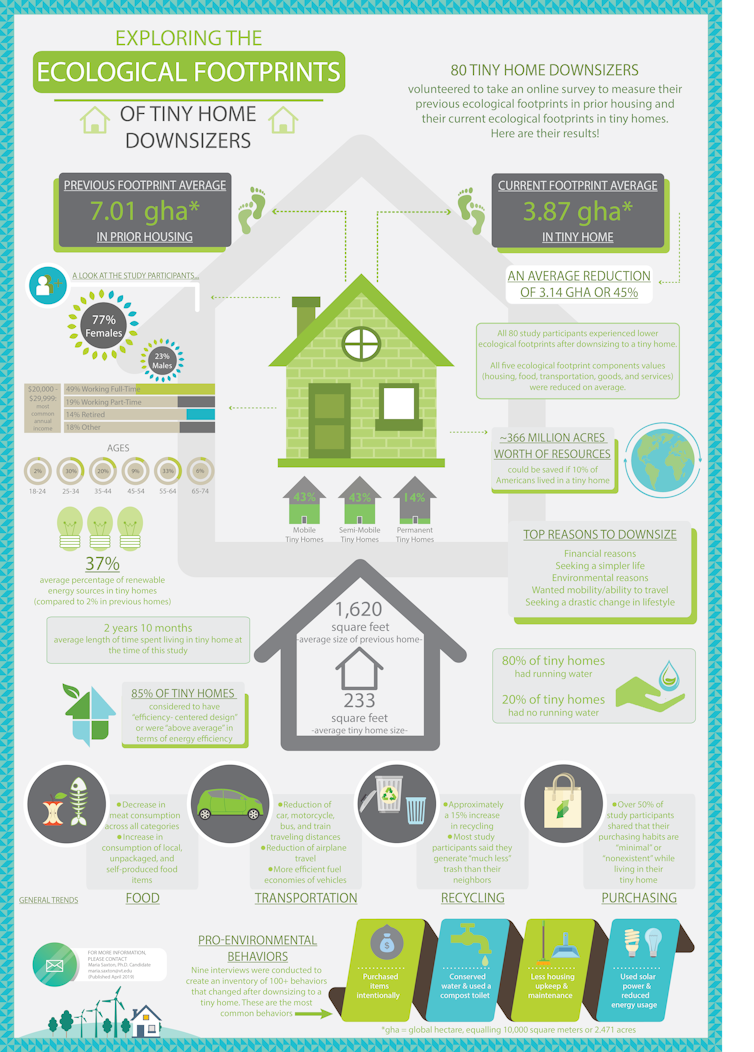

For my doctorate in environmental design and planning, I sought to fill this gap in knowledge by developing a study that could provide measurable evidence on how downsizing influences environmental impacts. First I surveyed 80 downsizers who had lived in tiny homes for a year or more, to calculate their ecological footprints in prior housing and current ecological footprints in their tiny houses. Then I conducted nine in-depth interviews to learn about behaviors that changed after downsizing.

I found that among 80 tiny-home downsizers located across the United States, ecological footprints were reduced by about 45 percent on average. Surprisingly, I found that downsizing can influence many parts of one’s lifestyle and reduce impacts on the environment in unexpected ways.

The unsustainable US housing model

In recent decades, the building trend has been to “go big.” Newly constructed homes in the United States generally have a larger average square footage than in any other country in the world.

In 1973 the average newly constructed U.S. home measured 1,660 square feet. By 2017 that average had increased to 2,631 square feet – a 63 percent increase. This growth has harmed the environment in many ways, including loss of green space, increased air pollution and energy consumption, and ecosystem fragmentation, which can reduce biodiversity.

The concept of minimalist living has existed for centuries, but the modern tiny-house movement became a trend only in the early 2000s, when one of the first tiny-home building companies was founded. Tiny homes are an innovative housing approach that can reduce building material waste and excessive consumption. There is no universal definition for a tiny home, but they generally are small, efficient spaces that value quality over quantity.

People choose to downsize to tiny homes for many reasons. They may include living a more environmentally friendly lifestyle, simplifying their lives and possessions, becoming more mobile or achieving financial freedom, since tiny homes typically cost significantly less than the average American home.

Many assessments of the tiny-house movement have asserted without quantitative evidence that individuals who downsize to tiny homes will have a significantly lower environmental impact. On the other hand, some reviews hint that tiny-home living may lend itself to unsustainable practices.

Understanding footprint changes after downsizing

This study examined tiny-home downsizers’ environmental impacts by measuring their individual ecological footprints. This metric calculates human demand on nature by providing a measurement of land needed to sustain current consumption behaviors.

To do this, I calculated their spatial footprints in terms of global hectares, considering housing, transportation, food, goods and services. For reference, one global hectare is equivalent to about 2.5 acres, or about the size of a single soccer field.

I found that among 80 tiny-home downsizers located across the United States, the average ecological footprint was 3.87 global hectares, or about 9.5 acres. This means that it would require 9.5 acres to support that person’s lifestyle for one year. Before moving into tiny homes, these respondents’ average footprint was 7.01 global hectares (17.3 acres). For comparison, the average American’s footprint is 8.4 global hectares, or 20.8 acres.

My most interesting finding was that housing was not the only component of participants’ ecological footprints that changed. On average, every major component of downsizers’ lifestyles, including food, transportation and consumption of goods and services, was positively influenced.

As a whole, I found that after downsizing people were more likely to eat less energy-intensive food products and adopt more environmentally conscious eating habits, such as eating more locally and growing more of their own food. Participants traveled less by car, motorcycle, bus, train and airplane, and drove more fuel-efficient cars than they did before downsizing.

They also purchased substantially fewer items, recycled more plastic and paper, and generated less trash. In sum, I found that downsizing was an important step toward reducing ecological footprints and encouraging pro-environmental behaviors.

To take these findings a step farther, I was able to use footprint data to calculate how many resources could potentially be saved if a small portion of Americans downsized. I found that about 366 million acres of biologically productive land could be saved if just 10 percent of Americans downsized to a tiny home.

Fine-tuning footprint analyses

My research identified more than 100 behaviors that changed after downsizing to a tiny home. Approximately 86 percent had a positive impact, while the rest were negative.

Some choices, such as harvesting rainwater, adopting a capsule wardrobe approach and carpooling, reduced individual environmental impacts. Others could potentially expand people’s footprints – for example, traveling more and eating out more often.

A handful of negative behaviors were not representative of all participants in the study, but still are important to discuss. For instance, some participants drove longer distances after moving to rural areas where their tiny homes could be parked. Others ate out more often because they had smaller kitchens, or recycled less because they lacked space to store recyclables and had less access to curbside recycling services.

It is important to identify these behaviors in order to understand potential negative implications of tiny-home living and enable designers to address them. It is also important to note that some behaviors I recorded could have been influenced by factors other than downsizing to a tiny home. For instance, some people might have reduced their car travel because they had recently retired.

Nonetheless, all participants in this study reduced their footprints by downsizing to tiny homes, even if they did not downsize for environmental reasons. This indicates that downsizing leads people to adopt behaviors that are better for the environment. These findings provide important insights for the sustainable housing industry and implications for future research on tiny homes.

For instance, someone may be able to present this study to a planning commission office in their town to show how and why tiny homes are a sustainable housing approach. These results have the potential to also support tiny-home builders and designers, people who want to create tiny-home communities and others trying to change zoning ordinances in their towns to support tiny homes. I hope this work will spur additional research that produces more affordable and sustainable housing choices for more Americans.

Maria Saxton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

The greatest risk of AI in higher education isn’t cheating – it’s the erosion of learning itself

Automating knowledge production and teaching weakens the ecosystem of students and scholars that sustains…

Your gut microbes can be anti-aging – scientists are uncovering how to keep your microbiome youthful

Certain lifestyle changes can help your gut microbiome help you age gracefully.

Florida’s immigrant entrepreneurs are creating jobs and prosperity in their communities

Stories of Florida’s immigrant entrepreneurs show how immigrants find opportunities and fill economic…