To preserve US national parks in a warming world, reconnect fragmented public lands

What is the best way to conserve US national parks in a climate-altered future? One answer is connecting parks and other public lands, so plants and animals can shift their ranges.

The Trump administration’s decision to keep many U.S. national parks open during the current federal government shutdown, with few or no staff, spotlights how popular and how vulnerable these unique places are.

Some states, such as Utah and Arizona, have spent heavily to keep parks open rather than lose tourist revenues. Unfortunately, without rangers to enforce rules, some visitors have strewn garbage and vandalized scenic areas.

The most urgent near-term priority for the park system is to either end the shutdown or cut off public access until it is over, and then restore order once staff can get back in. But beyond the shutdown, the park system faces broader threats, as I show in my book, “Grand Canyon for Sale.”

Climate change will force wild species in all national parks to adapt, often by migrating. The problem is that U.S. policies – especially under the Trump administration – are fragmenting connections between parks and other public lands that give natural systems better odds for survival.

Conservation islands

External threats to national parks aren’t new. Politicians started trying to protect the Grand Canyon from private interests in the 1880s. Finally, in 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt used his power under the Antiquities Act to designate the canyon as a national monument.

During a visit to the canyon, Roosevelt told onlookers, “I hope that you will not … mar the wonderful grandeur, the sublimity, the loneliness and beauty of the Canyon. Leave it as it is. You can not improve on it.” A decade later, President Woodrow Wilson signed the bill that created Grand Canyon National Park on Feb. 26, 1919.

Aggressive and well-financed private industries, including logging, mining, grazing, energy production and real estate development, operate on other public lands, where they often pose threats to plants and wildlife. By expanding development and fragmenting existing tracts of land, they also shut down future survival prospects for wild species in the national parks themselves.

Parks in a changing climate

Over all of these issues looms the broadest threat: climate change. According to a meta-analysis of 123 research studies conducted between 1990 and 2010, nearly all the land administered by the National Park Service is located in areas of observed warming in the 20th century. And a 2018 study showed that the parks are bearing the brunt of climate change because many are located in regions that are hotter and drier than the nation as a whole.

Part of the National Park Service’s mission is to conserve wild species and natural systems in the parks “by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” Climate change makes this an epic challenge. For example, Grand Canyon National Park’s climate change action plan warns of more frequent droughts, habitat fragmentation, more frequent and intense wildfires and floods, and shrinking waterflows in the Colorado River.

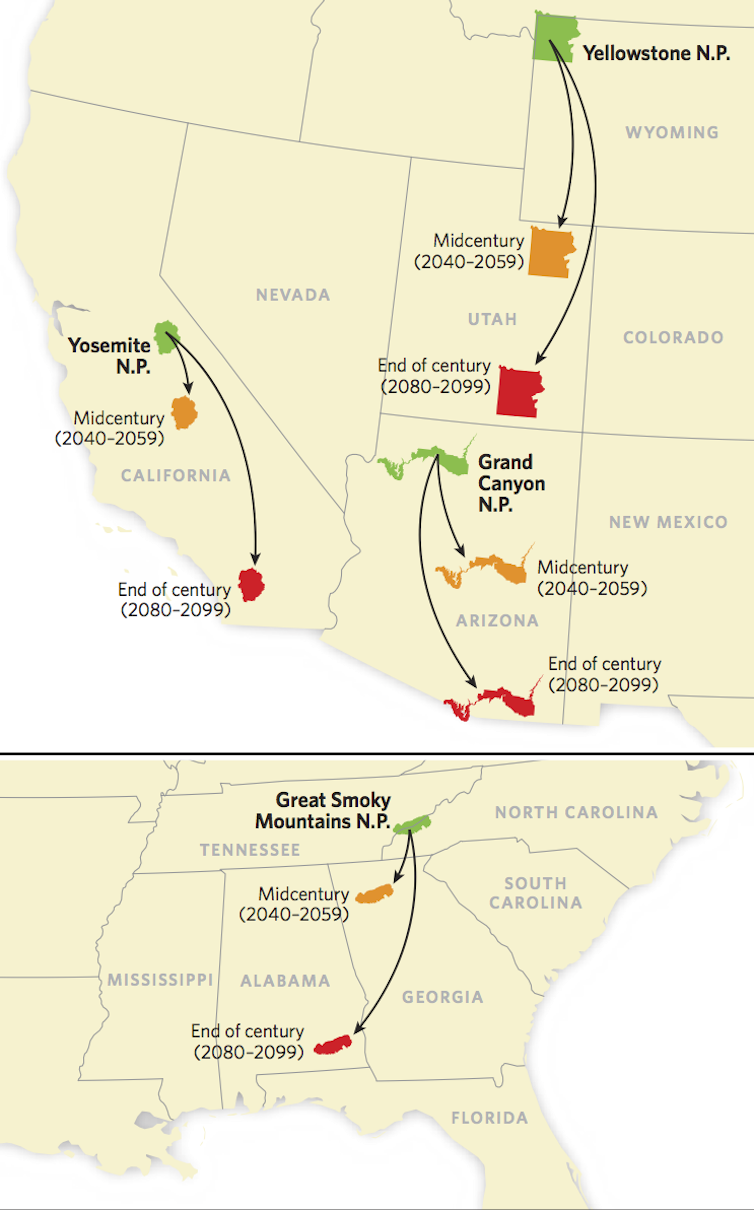

And, of course, the gathering heat. In effect, many national parks’ climates will move two or three hundred miles south during this century. By 2100, if global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, Grand Canyon will be as hot as the climate now is along the Mexican border. The climate of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the most popular in the system, will slide nearly to Florida. As soon as two decades from now, according to the latest U.S. national climate assessment, the Grand Canyon region and its wild species could endure 40 to 50 more days with temperatures over 90 degrees yearly.

Similar changes are occurring throughout the park system. Glaciers are disappearing from Glacier National Park in Montana. Giant sequoia trees in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks in California are threatened by heat, fire and insects. Rising seas are starting to inundate dozens of parks along coastlines, from Florida’s Dry Tortugas to Alaska’s Bering Land Bridge.

Creating escape routes

As climate zones shift, many plants and animals will need to migrate into or out of protected natural areas to stay within temperature and moisture ranges where they have evolved over thousands of years. Scientists are outlining plans to ensure futures for at least some of these species by making it easier for them to move to different habitats. But studies on “climate connectivity” warn that if public lands around national parks are used for drilling, mining, logging and commercial development, they won’t function as survival paths for wild species.

“You can’t manage a national park by itself. That’s increasingly a strategy for failure,” Northern Arizona University biologist Paul Beier told me. “Your park is embedded in the landscape, and we have to get smart about managing the entire landscape, because the climate is moving.”

This research signals that if the goal is to guard the endurance of wild species for future generations, Congress and federal agencies will need to find new ways of managing the nation’s million square miles of federal public lands. National parks will need to depend on healthy adjacent national forests, wildlife refuges, monuments and rangelands, maintained in their natural state.

In a 2017 study, researchers found that creating links among isolated preserves was a suprisingly effective way to maintain wild bird populations in Africa and Brazil. “The issues in the American West are the same,” Duke University ecologist and study co-author Stuart Pimm told me. “A lot of the West is protected, but it’s fragmented. Reestablishing that connectivity among public lands will give animals a chance to move, slowing down rates of local extinction.”

Promoting extractive use

However, the Trump administration is opening public lands in pursuit of “energy dominance.” The Interior Department has removed millions of acres from national monuments and opened them for uses such as logging and mining. Oil and gas leasing on public lands has tripled since President Trump assumed office.

Public lands generate wealth for other private interests, too. In the West, some 400,000 square miles managed by the Interior Department and Forest Service are leased for cattle ranching. These acres provide only one percent of our national supply of beef, but studies have documented that livestock grazing across the west can foul water sources, erode soil and severely diminish survival chances for wild species.

The lease programs cost the government more than six times as much to administer as they bring in. According to data that I obtained from federal agencies, most leases are held by very large, often absentee cattle operators and by corporate interests.

In contrast, studies by federal agencies and private researchers show that even in raw economic terms, healthy and protected landscapes are worth tens of billions of dollars to their owners – the American public – each year.

Meanwhile, climate change ratchets up. Preserving the nature of U.S. national parks will require connecting and protecting all of America’s public lands.

Stephen Nash does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

CIA agents successfully executed a plan for regime change in Iran in 1953 – but Trump hasn’t reveale

A covert US campaign in the mid-20th century helped steer Iran toward the intense anti-American sentiment…

Public defender shortage is leading to hundreds of criminal cases being dismissed

There are never enough lawyers to provide indigent defense, but the situation has gotten worse since…

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…