The Trump administration is scrapping a collaborative sage grouse protection plan to expand oil and

The Interior Department is expanding oil and gas leasing on land in six western states that is vital habitat for the greater sage grouse. Lawsuits are certain to follow.

The Trump administration has released plans to open up nine million acres of sage grouse habitat in six western states to oil and gas drilling. This initiative dramatically cuts back an elaborate plan developed under the Obama administration to steer energy development away from sage grouse habitat. Predictably, environmentalists oppose it and the energy industry supports it.

Controversies over protecting sage grouse are part of a continuing struggle over management of Western public lands. Like its Republican predecessors, the Trump administration is prioritizing use of public lands and resources over conservation. The question is whether its revisions will protect sage grouse and their habitat effectively enough to keep the birds off the endangered species list – the outcome that the Obama plan was designed to achieve.

Sage grouse under siege

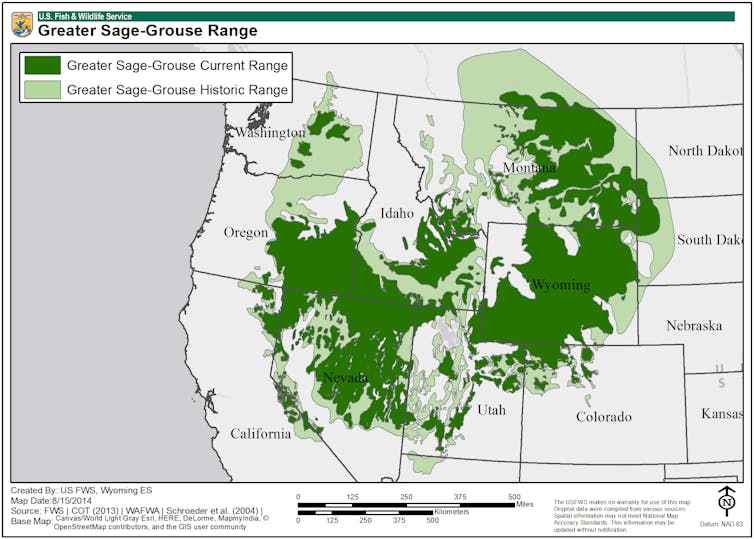

The greater sage grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus), which is known for its dramatic mating displays, is found from the Rocky Mountains on the east to the Sierra and Cascade mountain ranges on the west. Before European settlement, sage grouse numbered up to 16 million. Today their population has shrunk to an estimated 200,000 to 500,000. The main cause is habitat loss due to road construction, development and oil and gas leasing.

More frequent wildland fires are also a factor. After wildfires, invasive species like cheatgrass are first to appear and replace the sagebrush that grouse rely on for food and cover. Climate change and drought also contribute to increased fire regimes, and the cycle repeats itself.

Concern over the sage grouse’s decline spurred five petitions to list it for protection under the Endangered Species Act between 1999 and 2005. Listing a species requires federal agencies to ensure that any actions they fund, authorize or carry out – such as awarding mining leases or drilling permits – will not threaten the species or its critical habitat.

In 2005 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared that listing the sage grouse was “not warranted.” These decisions are supposed to be based on science, but leaks revealed that an agency synthesis of sage grouse research had been edited by a political appointee who deleted scientific references without discussion. In a section that discussed whether grouse could access the types of sagebrush they prefer to feed on in winter, the appointee asserted, “I believe that is an overstatement, as they will eat other stuff if it’s available.”

In 2010 the agency ruled that the sage grouse was at risk of extinction, but declined to list it at that time, although Interior Secretary Ken Salazar pledged to take steps to restore sagebrush habitat. In a court settlement, the agency agreed to issue a listing decision by September 30, 2015.

Negotiating a rescue plan

The Obama administration launched a concerted effort in 2011 to develop enough actions and plans at the federal and state level to avoid listing the sage grouse. California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada and Wyoming all developed plans for conserving sage grouse and their habitat. The U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management revised 98 land use plans in 10 states. And the U.S. Department of Agriculture provided funding for voluntary conservation actions on private lands.

In 2015 Interior Secretary Sally Jewell announced that these actions had reduced threats to sage grouse habitat so effectively that a listing was no longer necessary. A bipartisan group of Western governors joined Jewell for the event. But despite the good feelings, some important value conflicts remained unresolved.

Notably, the plan created zones called Sagebrush Focal Areas – spaces deemed essential for the sage grouse to survive – and proposed to bar mineral development on ten million acres within those areas. Some Western governors were surprised by this provision and felt that officials in Washington, D.C. had dropped it on the states without consultation.

The Interior Department has decided not to create Sagebrush Focal Areas, and will allow mining and energy development in these zones to expand. Agency records show that as officials reevaluated the sage grouse plan in 2017, they worked closely with oil, gas and mining industry representatives, but not with environmental advocates.

A more collaborative approach

Many government officials and Westerners would like to find ways to manage public lands and resources that avoid high-level political decisions followed by endless litigation. Over the past decade, a more collaborative model has been evolving in fits and starts.

In addition to the Obama administration’s sage grouse negotiations, recent examples include a Western Working Lands Forum organized by the Western Governors’ Association in March 2018, and forest collaborations in Idaho that include diverse members and work to balance timber production, jobs and ecological restoration in national forests. At times the West has seemed to be lurching towards some form of collaborative land discussions, where states and similar entities are given more equal standing than simply being classified as “stakeholders,” a term that I know rankles many among them.

For such initiatives to succeed, they must give elected officials and high-level administrative appointees some cover to support locally and regionally crafted solutions. They also have to prevent federal officials from overruling outcomes with which they disagree.

When the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced in 2015 that listing the sage grouse was not warranted, the agency committed to revisit the bird’s status in 2010. To assess how expanded energy production affects sage grouse, federal agencies will need to conduct rigorous monitoring in the affected areas. But the Trump administration has deemphasized use of science to inform decision making, so it is not clear whether such monitoring will take place, or whether federal decision makers will heed its findings.

Under the Trump administration’s plan, states are to take the lead in finding ways to mitigate impacts of energy development on sage grouse. Perhaps the governors of the six affected states – three Republicans and three Democrats – can find more collaborative ways to balance sage grouse protection against resource use.

Editor’s note: This is an updated version of an article originally published on May 31, 2018.

John Freemuth receives funding from USGS and BLM.

Read These Next

Why ICE’s body camera policies make the videos unlikely to improve accountability and transparency

For body cameras to function as transparency tools, wrongdoing would have to be consistently penalized,…

Honoring Colorado’s Black History requires taking the time to tell stories that make us think twice

This year marks the 150th birthday of Colorado and is a chance to examine the state’s history.

When civil rights protesters are killed, some deaths – generally those of white people – resonate mo

From the civil rights era of the 1960s until today, white victims of government violence have received…