Fishing forecasts can predict marine creature movements

A new tool called EcoCast helps fishermen in the West Coast figure out where it's best to fish that day.

Do you check the weather forecast before getting dressed in the morning?

If you do, then you’re making a decision in real time, based on dynamic processes that can vary greatly over space and time. Marine animals can be similarly dynamic. They might move in response to constantly shifting ocean conditions, like currents and fronts.

That led us to wonder: Can we predict marine wildlife like meteorologists predict the weather, so fisherman can make real-time decisions on the water? Our team has been studying established tools like those used for weather forecasts, so we can develop a new program that estimates where marine species are likely to be each day. Unlike a weather forecast, our tool can’t help you decide if you need an umbrella or sunglasses, but it can help fishermen decide where to fish.

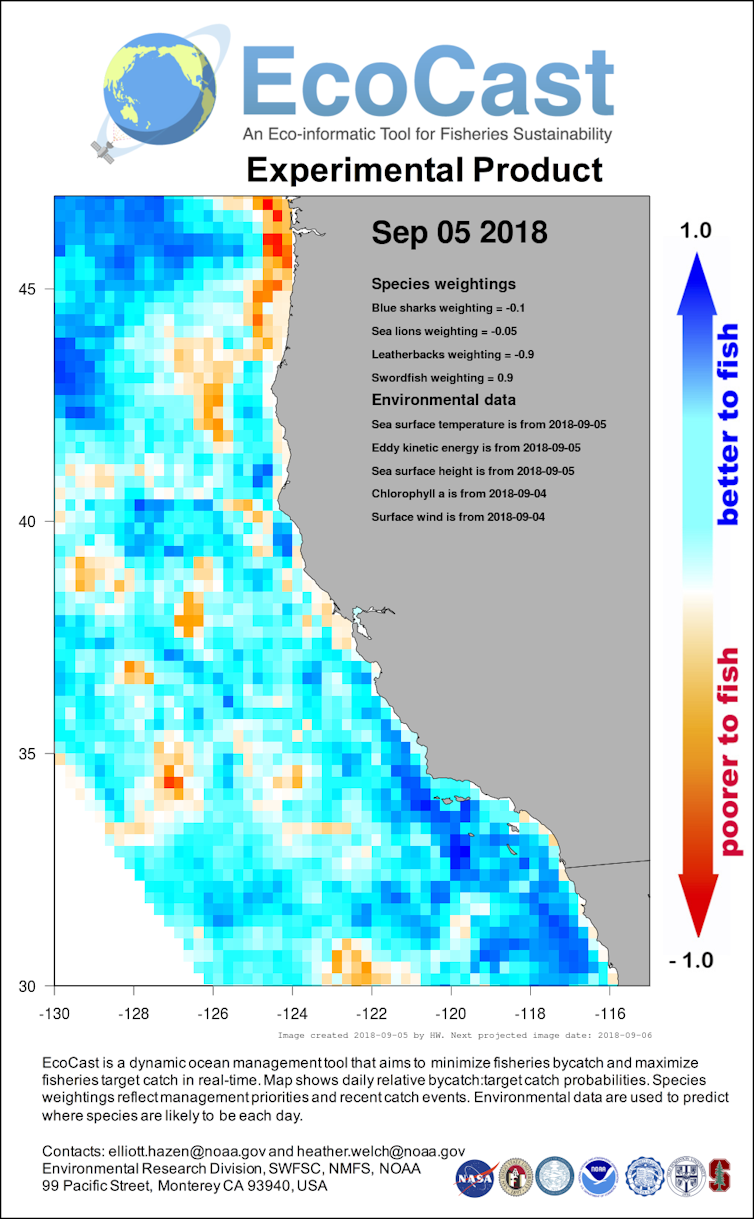

Our new application, called EcoCast, launched late in 2017. It was created specifically for swordfish fisherman on the U.S. West Coast, so they can avoid protected species like leatherback turtles and California sea lions, often referred to as “bycatch.” These predictions are designed to help fishermen figure out where they are most likely to find the species they want to catch and least likely to find the species they want to avoid.

Making predictions

To create the EcoCast tool, we studied examples of established tools that make real-time predictions, such as weather forecasts, hurricane outlooks and wildfire incident alerts.

We found that these tools all follow a similar workflow. First, they acquire data on current environmental conditions. For example, the National Hurricane Center flies airplanes through storm systems to acquire data on hurricane characteristics. The U.S. Forest Service accesses new imagery from satellite-borne sensors to observe fires from space.

Then, these tools predict their target features based on this new data. For example, the National Hurricane Center predicts hurricane location, intensity and movement. These predictions are then distributed to the public – perhaps through RSS feeds, texts or radio alerts. Finally, these predictions are automated. For example, the National Hurricane Center and the U.S. Forest Service create new hurricane and wildfire predictions every six hours. The National Weather Service creates daily forecasts.

We designed EcoCast to follow the same workflow. Each day, current satellite data such as sea surface temperature, chlorophyll concentration and sea surface height are acquired from online repositories. This data helps us understand current oceanic conditions.

Then, we use mathematical models to predict the distributions of swordfish, turtles, sea lions and sharks. The models are tuned to each species’ environmental preferences. When we combine these models with data on current oceanic conditions, we can predict where species are most likely to be in real time. When we tested the models, we found they performed well in distinguishing between where species were or were not located.

Next, we overlay the predicted species distributions to determine the ratio of swordfish, the target species, to the bycatch species – turtles, sea lions and sharks – in roughly 25 by 25 kilometer blocks. This map, available online, helps fishermen locate areas that are optimal for finding swordfish while avoiding bycatch species. For consistency, we scale each day’s map between 1 and negative 1, where areas valued closer to 1 are better to fish and negative 1 are poorer to fish. We automated the EcoCast tool to run every morning in order to produce a new map each day.

Looking forward

Thanks to increasing technological capacity and data availability, there are many predictive tools under development to help guide marine decisions.

For example, an international group of researchers is currently developing FORE-C, a coral disease outbreak forecasting tool for the western tropical Pacific Ocean. A tool called WhaleWatch is being updated and expanded to help commercial vessels slow down or alter their shipping routes to avoid blue whale strikes offshore California. Another tool was recently launched to address the bycatch of Atlantic sturgeon in the Delaware Bay.

Predictive tools can be applied in situations with limited data, too. For example, another tool is under development by NOAA and an interdisciplinary group of researchers to guide the timing of a fishery closure in Southern California, designed to avoid bycatch of loggerhead turtles.

These tools reflect how digital technologies can improve marine management and conservation by integrating existing data. That’s crucial for helping stakeholders to make decisions about an ever-changing world.

Heather Welch has received funding from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the National Aeronautic and Space Administration.

Elliott Hazen has received funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the National Aeronautic and Space Administration, and California Seagrant for this work.

Stephanie Brodie has received funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the National Aeronautic and Space Administration, and California Seagrant for this work.

Read These Next

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…

Massive US attacks on Iran unlikely to produce regime change in Tehran

President Trump has appealed to Iranians to topple their government, but a popular uprising is unlikely…

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…