All wildfires are not alike, but the US is fighting them that way

A historian of wildfires explains the difference between urban and rural fire cultures, and what it means for protecting communities in fire-prone rural areas.

So far, the 2018 fire season has produced a handful of big fires in California, Nevada, New Mexico and Colorado; conflagrations in Oklahoma and Kansas; and a fire bust in Alaska, along with garden-variety wildfires from Florida to Oregon. Some of those fires are in rural areas, some are in wildlands, and a few are in exurbs.

Even in a time of new normals, this looks pretty typical. Fire starts are a little below the 10-year running average, and the amount of burned area is running above that average. But no one can predict what may happen in the coming months. California thought it had dodged a bullet in 2017, until a swarm of wildfires in late fall blasted through Napa and Sonoma counties, followed by the Big One – the Thomas fire, California’s largest on record, in Ventura and Santa Barbara.

Every major fire rekindles another round of commentaries about “America’s wildfire problem.” But the fact is that our nation does not have a fire problem. It has many fire problems, and they require different strategies. Some problem fires have technical solutions, some demand cultural calls. All are political.

Here’s one idea: It’s time to rethink firefighting in the geekily labeled wildland-urban interface, or WUI – zones where human development intermingles with forests, grasslands and other feral vegetation.

It’s a dumb name because the boundary is not really an interface but an intermix, in which houses and natural vegetation abut and scramble in an ecological omelet. It’s a dumb problem because we know how to keep houses from burning – but we have had to relearn that in WUI zones, hardening houses and landscaping their communities is the best defense. This is a local task, not a federal one, though the federal agencies have a supporting role and can, and do, help build local capacity.

Two fire cultures

America is recolonizing rural landscapes everywhere, and fire in the WUI is one outcome. The concept appeared and received its name in Southern California, but has long since spread throughout the West. Some of the worst WUI risks reside in the southeastern United States, though they have mostly remained latent. Then a deadly blaze like the one that blew through Gatlinburg, Tennessee, to the fringes of Dollywood in 2016 reveals the full extent of the risk.

Just as development has stirred together built and natural landscapes, it also has juxtaposed two immiscible cultures of fire. Urban and wildland fire agencies are as different as fire hydrants and drip torches.

The mantra of urban fire control is “Learn not to burn.” Every fire is an existential threat to life and property, and the core goal of fire codes is protecting lives. Urban firefighters wear turnout coats, helmets and self-contained breathing apparatus. They pummel fires with water and often operate inside structures.

For wildlands, the central code is “Learn to live with fire.” Firefighters wear hardhats, carry shovels and Pulaskis, and wear bandannas. They work in woods, prairies and chaparral, spray dirt as often as water, and secure perimeters by setting fires to remove flammable vegetation between the flaming front and their control lines. Their great challenge is to restore good fire to biotas that hunger for it.

The training that each group gets is largely worthless in the other’s setting. There are a few instances of cross-training, particularly in rural areas, but the prime example of a major agency that tries to cope with both types of threats is the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, known as Cal Fire. Its experience shows what fusing these two purposes can mean.

Mixing the missions

Cal Fire began as the California Department of Forestry, a land management agency, albeit one with serious fire responsibilities. In 1974, under the pressures of postwar development, it became the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. In 2007 it collapsed that mission into Cal Fire, which operates like an urban fire service in the woods.

Decades ago, federal fire agencies gave up on suppression as a sole strategy. They recognized that the best way to control fire is to control the landscape, preferably through fire, and that eliminating all fires in places that have grown up with them only creates conditions that make wildfires worse. By contrast, for Cal Fire, the urgency of fires rolling into communities trumps all other tasks. If the last firefight fails, it has to double down for the next one.

Today the WUI is exerting a similar transformation at the national level. It threatens to become a black hole in America’s pyrogeography, drawing federal land agencies – primarily the U.S. Forest Service and the Interior Department’s Bureau of Land Management – away from managing fire as a means of managing land, and transforming them into urban fire-service surrogates and auxiliaries.

These agencies can and do help communities prepare for fires, but they do not have the tools, training or temperament to fight fire on an urban model. Cal Fire’s template is too expensive; moreover, it sucks resources away from managing fire well on the land, so it is too ineffective to serve nationally.

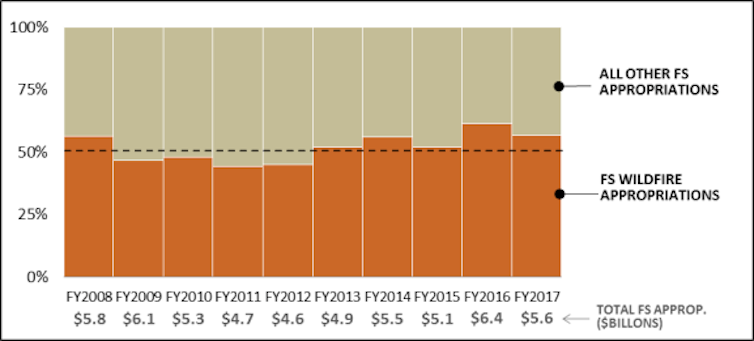

Turning the U.S. Forest Service into a National Fire Service may bring some relief to the WUI, but this would undermine the other missions in the agency’s charter, and ultimately weaken its ability to manage landscape fire. Already its fire mission is consuming over 50 percent of the Forest Service’s annual budget.

Urban enclaves in the wild

Research repeatedly shows that the critical component in the WUI fire environment is the structure itself. Once a fire strikes the urban fringe it may morph into an urban conflagration, spreading from structure to structure, as happened in Santa Rosa, California, last fall. Clearly, the wildland fire community has to improve fire resilience in its lands, which should reduce the intensity of the threat. But the real action is in the built environment.

The fact that so many horrendous fires have started from power lines illustrates how fires mediate between the land and the ways we choose to live on it. Strengthening structures, bolstering urban fire services, treating WUI areas as built environment – this is where we will get the greatest paybacks.

In effect, we need to pick up the other end of the WUI stick. Think of these areas not as wildlands encumbered by houses, but as urban or exurban enclaves with peculiar landscaping. Defining the issue as fundamentally a wildland problem makes fixes difficult. Defining it as an urban problem makes solutions quickly apparent. The goal should be to segregate the two fire cultures and their habitats, and let each do what it does best.

Americans learned long ago how to keep cities from burning. And then, it seems, we forgot.

Stephen Pyne has received funding from US Forest Service, Department of the Interior, and Joint Fire Science Program.

Read These Next

CIA agents successfully executed a plan for regime change in Iran in 1953 – but Trump hasn’t reveale

A covert US campaign in the mid-20th century helped steer Iran toward the intense anti-American sentiment…

Iran’s targeting of airport, ports and hotels in reaction to US strikes has forced Gulf nations onto

Qatar, the UAE and other Gulf nations have spent years cultivating an image of being an oasis of stability…

‘Destruction is not the same as political success’: US bombing of Iran shows little evidence of endg

As US bombing operations in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya have shown, destruction is not the same as political…