Trump proposal to weaken project reviews threatens the 'Magna Carta of environmental law'

Do environmental reviews delay large-scale projects? The Trump administration says yes, but studies show that these reviews lead to better results and can even save time and money.

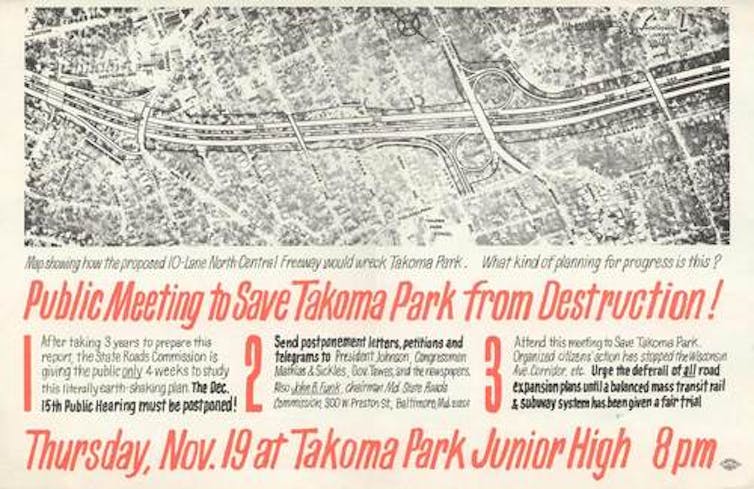

Building the U.S. Interstate highway system in the 1950s and 60s is often cited as one of government’s great achievements. But it had harmful impacts too. Many city communities were bulldozed to make space for freeways. Across the nation, people vigorously objected to having no say in these decisions, leading to “freeway revolts.”

This outcry, coupled with the growing environmental movement, gave rise to the idea – which were revolutionary at the time – that agencies should take a hard look at the environmental impacts of their actions, consider reasonable alternatives and allow community input. The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), enacted in 1970, codified these principles and allowed citizens to sue if they believed government had not complied. Because it represents a turning point in thinking about environmental protection, NEPA has been called the “Magna Carta of environmental law.”

Despite NEPA’s demonstrated successes, critics have attacked it for years, usually based on anecdotes claiming that lengthy environmental reviews caused project delays. President Donald Trump’s infrastructure initiative is the latest example. And on May 3, 2018, the Trump administration announced that it will soon propose changes to the rules that guide federal agencies carrying out NEPA reviews.

As attorneys who held senior positions at the Environmental Protection Agency during the Obama administration, including managing the agency’s NEPA office, we have extensive experience with NEPA reviews. Expert studies reveal a vast disconnect between the evidence, which shows that NEPA is not the cause of project delays, and the sweeping changes that NEPA critics are proposing. This disconnect reveals that current proposals aren’t really about speeding up projects, but are instead part of a broad deregulatory agenda that prioritizes business interests over public benefits from environmental protection.

NEPA reviews aren’t the cause of project delays

Over more than four decades, NEPA has helped government agencies make smarter choices about public infrastructure, reducing damage to both natural environments and communities and avoiding the costs of correcting ill-considered projects.

For example, in the 1990s Michigan’s state transportation agency wanted to build a four-lane highway across a huge swath of important wetlands. Using NEPA, citizens forced the state to consider alternatives. Ultimately the state decided to expand an existing highway instead, dramatically reducing environmental harm and saving US$1.5 billion. Similar stories have occurred across the country.

Critics have long used “NEPA is slowing projects down!” as their rallying cry. Independent experts have looked at the evidence and reached a different conclusion.

The most authoritative independent studies were done by the Government Accounting Office in 2014 and the Congressional Research Service in 2011 and 2012. They found that the vast majority of projects have very streamlined reviews.

About 95 percent of all projects subject to NEPA go through a very short process called a “categorical exclusion” that usually takes from a few days to a few months. Another 4 percent have a short and straightforward review, called an “environmental assessment,” that usually takes between four and 18 months. Less than 1 percent of projects are subject to a full review, which is called an “environmental impact statement.”

Typically, these are large-scale initiatives such as a new highway, a major dredging project or a multistate pipeline. You wouldn’t know it from rhetoric in Washington, but the sweeping changes being proposed to NEPA are focused on less than 1 percent of projects.

These independent investigations also found that NEPA reviews are not the reason that the biggest projects take time. State and local issues, such as funding shortfalls, changing priorities and local controversy, are the most significant influence on whether a project moves forward quickly or takes longer than anticipated. Of course, there are examples where environmental reviews took too long, but in many cases these reviews started and stopped for reasons unrelated to environmental issues.

In fact, by requiring agencies to consider alternatives to their envisioned projects, environmental reviews can speed things up by identifying better options and solving problems that could be costly or cause delays in the long run – a common issue in highway construction, for example. As our shop teachers advised, “Measure twice, cut once.” This is one reason why federal agencies that use NEPA most, including the Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service and the Department of Energy, have long voiced support for it.

Not about efficiency

Enshrining unsupported policy in statutes passed by Congress makes those choices much harder to fix. Here’s what the president wants to do that would require changing the law:

– Take environmental agencies out of NEPA reviews. Congress recognized that some federal agencies are focused on building things, like highways or energy projects, and that protecting the environment is not their mission or area of expertise. That’s why it gave EPA a central role in NEPA studies by other agencies.

EPA involvement has helped reduce adverse environmental impacts through early up front coordination, without adding time. The agency routinely produces its comments within 30 days. The Trump infrastructure plan proposes to eliminate EPA’s review role.

– Cut a huge hole in consideration of alternatives. The Trump proposal would insert waffle words, like provisions limiting alternatives to those that the applicant finds “economically feasible” or are within the applicant’s “capability,” into NEPA’s requirement for agencies to consider reasonable alternatives. This approach allows applicants to avoid considering options they don’t like.

Consideration of alternatives is the heart of NEPA. Thinking hard about how projects can be done with less environmental damage – for example, by reusing an already developed site instead of paving over open space – improves designs, saves money and builds public support.

– Set the stage for getting rid of NEPA completely. In case anyone misses the point, the Trump plan allows some projects to bypass all environmental reviews on a “pilot” basis. A recent report by the conservative Heritage Foundation follows the same playbook by calling for repeal of NEPA.

Change NEPA practice, not the law

Over the last 45 years federal agencies have improved their processes for carrying out NEPA reviews, through steps such as providing more up front consultation. The Obama administration was continuing that effort with a number of consensus efficiency improvements that show promise for speeding things up without undercutting NEPA’s important goals.

By requiring government agencies to think before they act, NEPA has avoided countless harmful and ill-considered ideas. As the secretary of energy said in 1992, after halting a project that would have cost billions, “[T]hank God for NEPA because there were so many pressures to make a selection for a technology that might have been forced upon us and that would have been wrong for the country.”

Federal agencies should keep finding ways to implement NEPA more efficiently. What the federal government shouldn’t do is make enormous statutory changes based on incorrect claims about a fraction of 1 percent of projects – or disregard the lesson of the last 45 years that the most efficient choice is to build things right the first time.

Janet McCabe served as Deputy Assistant Administrator for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Air and Radiation (OAR) from 2009 to 2013, and as Acting Assistant Administrator for OAR from 2013-2017. She is a senior law fellow at the Environmental Law and Policy Center and a member of Duke Energy's Indiana Citizens Advisory Board.

Cynthia Giles served as Assistant Administrator for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance from 2009 to 2017. She is currently the Director of Strategic Initiatives and Executive Fellow at the Energy & Environment Lab at the University of Chicago.

Read These Next

CIA agents successfully executed a plan for regime change in Iran in 1953 – but Trump hasn’t reveale

A covert US campaign in the mid-20th century helped steer Iran toward the intense anti-American sentiment…

Public defender shortage is leading to hundreds of criminal cases being dismissed

There are never enough lawyers to provide indigent defense, but the situation has gotten worse since…

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…