How weakened US fossil fuel regulations threaten environmental justice in Colorado

Many Coloradans feel powerless to protect themselves from pollution and other fallout caused by the state's fracking boom.

From the start, President Donald Trump’s administration has made dismantling regulations, especially for the oil, gas and coal industries, a top priority.

And though his claims of rolling back more regulations than any other administration are exaggerated, Trump’s team has tried hard to erase many environmental and energy-related rules.

Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke and Trump have teamed up with the Republican-led Congress to get federal agencies on the case, by streamlining environmental permitting and attempting other sweeping changes.

As an environmental sociologist who has spent hundreds of hours researching communities directly affected by oil and gas production, I find that many people living in these places feel that fossil fuel industries already had the upper hand before Trump took office.

Even among people who support drilling, many believe these industries need to be more regulated. The residents I have interviewed report feeling uncertain and vulnerable. They tell researchers like me they consider themselves powerless to control their surroundings or to protect the environment, their health or their property. Reducing regulations even more will only intensify these problems.

The fracking boom

Thanks to an oil and natural gas boom that began a decade ago, U.S. production of those fuels has hit new records. The nation now ranks as the world’s top natural gas producer. American oil output is beginning to rival Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Hydraulic fracturing and the directional drilling of shale rock formations, commonly called “fracking,” powered this surge. So did deregulation. Companies using these methods enjoyed significant exemptions from federal environmental regulations that date back to George W. Bush’s presidency and remained on the books throughout the Obama administration.

After the enactment of the 2005 Energy Policy Act, the law that codified many of these exemptions, states became responsible for creating their own policies, procedures, budgets and enforcement plans – most of which weren’t in place before the boom got underway. The government exempted fracking from federal environmental regulations like the Safe Drinking Water Act and the Clean Water Act.

States could decide rules like setbacks from homes, zoning, water acquisition and disposal, and most other aspects of drilling. This made it easier and quicker to permit hydraulic fracturing, but the states had to scramble to determine how to regulate it.

As fracking spread into more densely populated areas, wells ended up within a few hundred feet of homes, schools, hospitals and other buildings in states like Colorado, Texas, Pennsylvania and North Dakota. That made a big impact on people’s quality of life.

But in places like Denton, Texas, and Colorado’s Front Range – a booming region that stretches along the Rocky Mountains and includes cities like Fort Collins and Pueblo – the people who live in places most affected by these types of changes have no seat at the table. They live alongside oilfields and gas patches but have little power to affect what happens around them.

Health hazards and other problems

As a result, there’s a mounting debate regarding state and local control over oil and gas development. Having spoken to people affected by fracking’s spread, I believe it’s clear why people are demanding a bigger say.

A growing pool of scientific evidence indicates that living near oil and gas production can endanger public health. Rates of hospitalization, fatigue, certain childhood cancers and birth defects are higher, for one thing.

There’s also more air pollution, including methane emissions and smog, which have been linked to asthma in children. And communities near fracking operations are contending with loud noises, bright lights, vibrations and truck traffic, as well as contaminated water and soil.

Drilling and daily life

Colorado’s experience shows how oil and gas production can disrupt people’s daily lives, especially when the public is excluded from decisions about it. The state’s more than 50,000 permitted wells make Colorado a top producer of what the industry calls “unconventional” oil and gas. Its oil extraction has more than tripled since 2010, when the fracking boom began, and its natural gas production has more than doubled since 2001.

Like other states where oil and gas production has soared, Colorado struggles to balance the desires of drillers with local needs. In many communities, people living fracking sites say they are at risk. But Colorado’s state Supreme Court has ruled that only the state government can control where and when fracking may occur.

Weld County, which has small towns, subdivisions and rural areas where farmers raise cattle and plant grains and sugar beets, alone has at least 21,000 wells. It ranks 11th in oil production in the U.S. – and is the nation’s top agricultural producer outside California.

I belong to a team that unites social scientists, epidemiologists and statisticians. Together, we are completing a detailed study that measures how oil and gas drilling affects the quality of life in several Colorado communities. We have conducted surveys, in-depth interviews, ethnography and even taken blood and hair samples to examine how drilling may affect people’s stress levels and health, their daily lives and physical symptoms of stress, like elevated cortisol levels.

While doing this research, I have personally witnessed the toll that underregulation is taking. To collect our data, I’ve sat around kitchen tables and listened as people described their concerns about water quality, earthquakes and air pollution.

They are uncertain about how it affects the health of their children, grandchildren and elderly parents. I’ve visited once-idyllic homes, now set in the shadows of sound barrier walls standing 30 feet tall and stretching for hundreds of feet.

No way out

Coloradans who want to stop fracking and drilling near their homes now have two options. They can draft agreements about protocols with a willing operator – a process that often requires expensive legal advice and lots of time. Or, residents can locate an acceptable alternative site that is equally suitable for production – which of course only pushes risks into someone else’s backyard.

But some people have little recourse. Consider the situation facing Bella Romero Academy, a Weld County middle school. Its students are primarily Latino and belong to low-income households. Many have undocumented relatives.

Despite efforts by activists to block drilling, a company called Extraction Oil and Gas aims to place 24 well pads and other infrastructure within about 1,300 feet of the school and even closer to its athletic fields.

When activists protested as the site was prepared for drilling, one was arrested. Extraction is now suing several of these activists, along with unnamed “John and Jane Does.”

Environmental injustice

The Colorado context illustrates the lived reality of what researchers like me call “environmental injustice” amid the oil and gas development also afflicting other states.

People who live near drilling may be exposed to a wide array of environmental and health risks. In this way, they experience “distributive injustice,” due to their exposure to more than their fair share of pollutants and hazards. Hundreds of studies have shown that people of color, low-income communities and otherwise marginalized groups in the U.S. are more likely to be exposed to disproportionate environmental risks and hazards from polluting facilities and industrial activities.

The public has little power to zone or regulate oil and gas production near their homes, especially in states like Colorado. This is a form of “procedural inequality.”

When local governments try to restrict oil and gas production, they can face steep penalties meant to discourage local control.

The Trump administration’s efforts to further reduce federal regulations will surely escalate these sorts of injustices. Instead of serving the interests of communities where oil, gas and coal production takes place, I believe that its actions will disempower and divide the public.

Stephanie Malin's research regarding the impact of oil and gas drilling on communities in Colorado has received funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. She has also received funding from Colorado State University's Water Center.

Read These Next

Public defender shortage is leading to hundreds of criminal cases being dismissed

There are never enough lawyers to provide indigent defense, but the situation has gotten worse since…

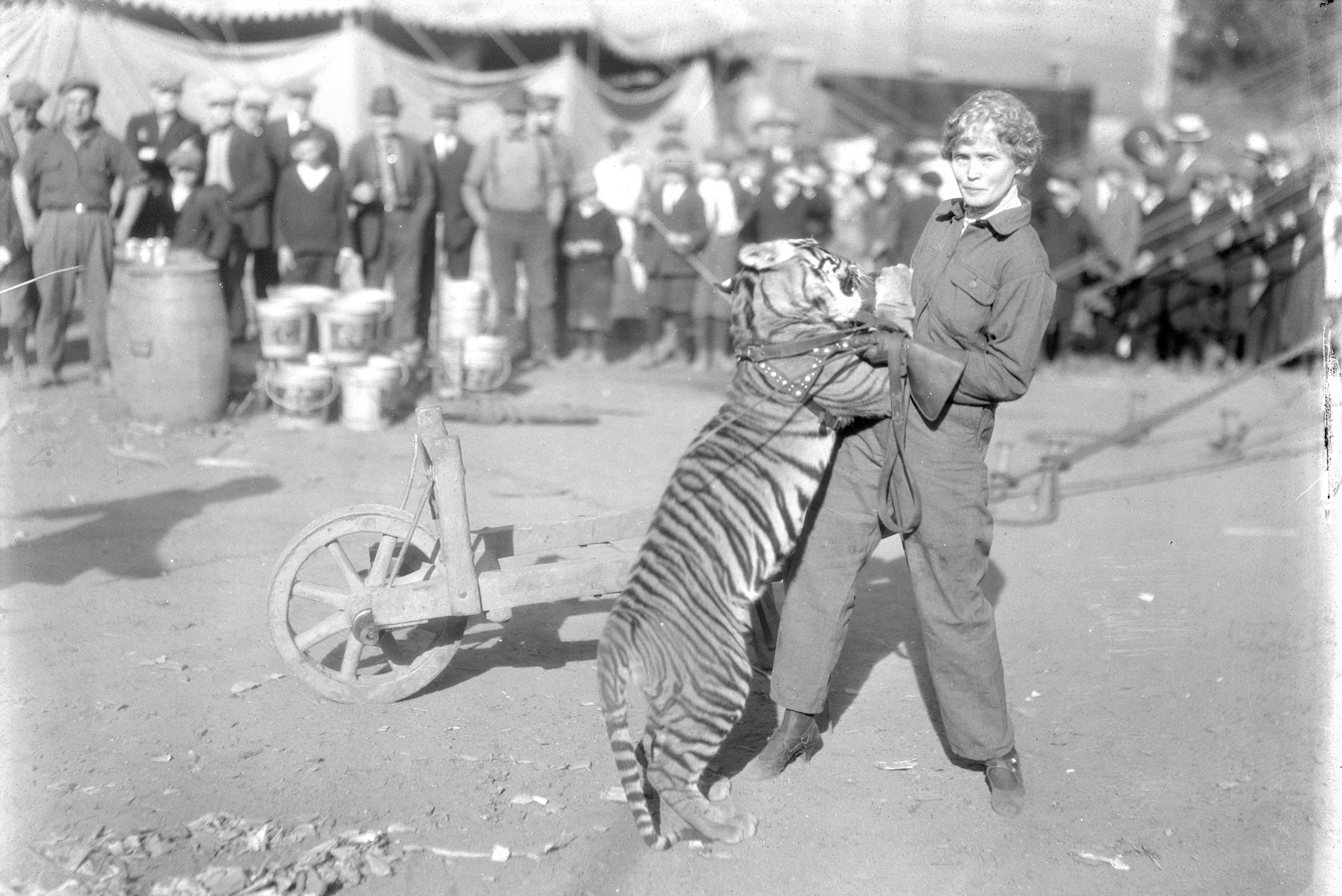

The inspiring and tragic story of Mabel Stark, America’s most famous female tiger trainer

Long before Joe Exotic became Tiger King, Mabel Stark reigned as Tiger Queen.

‘Destruction is not the same as political success’: US bombing of Iran shows little evidence of endg

As US bombing operations in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya have shown, destruction is not the same as political…