Turning power over to states won't improve protection for endangered species

Congress is moving to cut back the Endangered Species Act and give more power to states. But a recent study shows that state laws are weaker and states have few resources to protect species at risk.

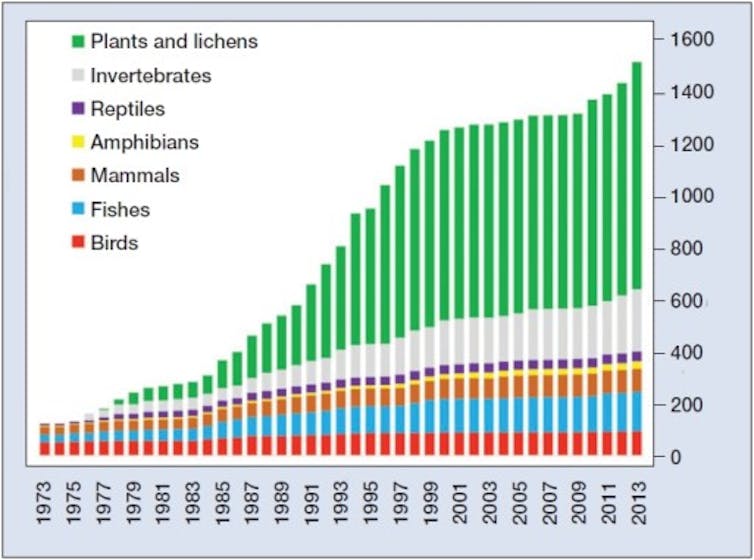

Since the Endangered Species Act became law in 1973, the U.S. government has played a critical role in protecting endangered and threatened species. But while the law is overwhelmingly popular with the American public, critics in Congress are proposing to significantly reduce federal authority to manage endangered species and delegate much of this role to state governments.

States have substantial authority to manage flora and fauna in their boundaries. But species often cross state borders, or exist on federal lands. And many states either are uninterested in species protection or prefer to rely on the federal government to serve that role.

We recently analyzed state endangered species laws and state funding to implement the Endangered Species Act. We concluded that relevant laws in most states are much weaker and less comprehensive than the federal Endangered Species Act. We also found that, in general, states contribute only a small fraction of total resources currently spent to implement the law.

In sum, many states currently are poorly equipped to assume the diverse responsibilities that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and NOAA Fisheries (collectively, “the Services”) handle today. In our view, therefore, devolving federal authority over endangered species management to the states will almost certainly weaken protections for those species and undermine conservation and recovery efforts.

Science-based decisions

The Endangered Species Act requires the Services to list and then protect endangered fish, wildlife and plants and their habitat, working with expert scientists, state authorities and citizens. It prohibits anyone from harming any listed species, and requires decisions about whether a species is endangered to be made “solely on the basis of the best scientific and commercial data available.” While costs are clearly relevant to protecting at-risk species, the law is clear that determinations about whether a species is endangered or likely to be harmed by a particular activity should not be based on the decision’s potential economic impacts.

In addition, the act directs the Services to cooperate as much as practical with states on conserving listed species. This may include actions such as signing management agreements and providing funding to state agencies. The law also allows citizens to petition to list species as endangered and file lawsuits to help enforce the Act.

Congress takes aim

Critics argue, often with little proof, that federal endangered species protection is too cumbersome and costly, and that the agencies act without sufficient input from states and localities. Some contend that endangered species protection can be more effectively and efficiently accomplished by state agencies alone.

The House Natural Resources Committee, chaired by Utah Republican Rob Bishop, has approved five bills that would weaken key provisions of the Endangered Species Act. These measures would:

- Allow the Services to deny that a species is endangered (and forgo protection of that species) due to economic impacts of listing.

- Require the Services to classify indiscriminately any data submitted by states, tribes or counties for listing decisions as “best available science.”

- Make it harder for citizens to challenge government actions under the ESA by limiting recovery of attorneys’ fees in citizen suits.

- Remove protection for at-risk non-native species within the United States.

- Lift federal protection for gray wolves in the Great Lakes states and Wyoming.

Observers expect similar legislation to be introduced in the Senate. And Utah Senators Mike Lee and Orrin Hatch have reintroduced a bill that would remove all federal ESA protection for species found within the borders of a single state. Such action would eliminate federal protection for hundreds of currently listed species, including the Florida panther and Florida manatee.

These legislators argue that states should play a larger role. When a federal appeals court found that the Endangered Species Act barred the Services from transferring management of federally threatened prairie dogs in Utah to the state in 2016, Bishop asserted that “Utahns have proven they can maintain prairie dogs. The only thing impeding the state is federal meddling.”

More recently, Wyoming Senator John Barrasso said, “Endangered species don’t care whether the federal government, or a state government, protects them. They just want to be protected.”

State laws are weaker and narrower

Our review shows that most states are poorly positioned to assume primary responsibility for endangered species protection. State laws generally are weaker and less comprehensive than the Endangered Species Act. West Virginia and Wyoming do not protect endangered species at all through state law. In 30 states, citizens are not allowed to petition for listing or delisting of a species.

Only 18 state laws protect all federally listed endangered species found in that state. Another 32 states provide less coverage than the federal statute. And 17 states do not cover endangered or threatened plants.

Only 27 states require use of scientific evidence in listing and delisting decisions. In 38 states, regulators are not required to consult with the state’s wildlife experts for state-level projects.

Unlike the Endangered Species Act, 38 state laws do not authorize regulators to designate critical habitat for threatened or endangered species – areas essential for those organisms to survive. Only two state laws require recovery planning, only five state laws restrict harm to important endangered species habitat, and only 16 states protect endangered species on privately owned lands.

Finally, state-reported expenditures make up only five percent of all annual spending to implement the Endangered Species Act. In short, states will need to massively increase spending to maintain current levels of protection.

Better ways to enhance state roles

We agree that there is a need for better collaboration between states and federal agencies. States and tribes may have important knowledge and data that can complement the substantial expertise and resources provided by federal authorities. But that information alone should not substitute for the science-based decision making required by the ESA.

Furthermore, the Endangered Species Act already provides ample opportunities for federal and state collaboration. Many charges of poor coordination appear to be thinly veiled attempts to reduce protections, rather than efforts to promote meaningful collaboration. In our view, effective coordination under the ESA requires an enduring commitment to conservation and recovery by both the Services and the partnering state.

Congress should find ways to provide more incentives for conservation on private lands, which provide habitat for nearly 80 percent of listed species. The Endangered Species Act already encourages federal collaboration with states and private landowners, and there are many examples of successful partnerships.

Several studies have shown that listing species and developing conservation and recovery plans improves their status, provided that recovery efforts are funded. Rather than dismantling the Endangered Species Act, Congress needs to provide more resources to achieve its goals. The most productive strategies would be increasing funding for listing, conservation and recovery; systematically implementing and enforcing the law; and developing strategies for managing looming stressors to ecosystems, such as global climate change.

Alejandro Camacho receives funding from the Doris Duke Foundation, and is a member scholar for the Center for Progressive Reform.

As director of the University of California, Irvine's environmental law clinic, Michael Robinson-Dorn represents non-governmental organizations on issues that at times involved the Endangered Species Act. None of his current cases involve devolution of power to the states. The study described in this article received funding from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

Read These Next

CIA agents successfully executed a plan for regime change in Iran in 1953 – but Trump hasn’t reveale

A covert US campaign in the mid-20th century helped steer Iran toward the intense anti-American sentiment…

Public defender shortage is leading to hundreds of criminal cases being dismissed

There are never enough lawyers to provide indigent defense, but the situation has gotten worse since…

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…