The obscure federal agency that soon could raise your electric bill: 5 questions answered on FERC

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission normally works in obscurity, but is in the spotlight as it considers a proposal to support coal and nuclear power plants that are having trouble competing.

Editor’s note: On or before Dec. 11, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is expected to take action on a controversial proposal by Energy Secretary Rick Perry that seeks to prevent noncompetitive coal and nuclear power plants from retiring prematurely. Depending on how such a rule is structured, analyses have estimated that it could cost ratepayers in affected regions up to several billion dollars yearly. Energy scholar Joshua Rhodes explains what FERC is and why it has so much power over energy markets and (indirectly) the prices consumers pay.

Why is this proposal so controversial?

Secretary Perry has asserted that “the resiliency of the electric grid is threatened by the premature retirements of…fuel-secure traditional baseload resources.” While exact details are not known, the rule Perry has proposed would “make whole” electric generators that can store 90 days of fuel on-site.

This means that even if those plants cannot make money in their respective markets (because other generators can provide electricity more cheaply), they will receive extra payments from the grid operator to recover their operating costs and provide a “fair” return on equity to plant owners. According to FERC Chair Neil Chatterjee, the extra money to keep those plants running will come from electricity customers in the affected areas.

Perry’s rationale is that by storing 90 days’ worth of fuel on-site, these plants make the power system more reliable, because they can run even if emergencies or disasters affect other fuel sources such as natural gas pipelines. Therefore, they should receive support that enables them to keep operating.

However, because this policy would benefit only coal and nuclear power plants – the only types that store fuel on-site – it has been interpreted as an excuse to subsidize plants that are struggling to compete. No shortage of ink has been spilled on this proposal, most of it very critical.

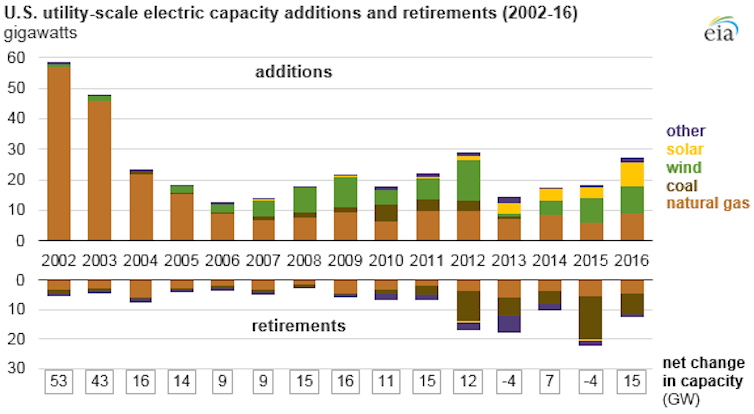

The counterview is that our electricity system is changing. The average U.S. coal plant is 45 years old, which is near the end of its expected operating life, and the average age of our nuclear fleet is 37 years old.

Some experts point to an analysis by the Rhodium Group that shows fuel supply to be responsible for only 0.00007 percent of electricity disruptions. Opponents of Perry’s proposal argue that other available options, such as wind and solar power, are cheaper and cleaner than coal, and will produce power at more stable prices.

Moreover, under the Federal Power Act, FERC is not supposed to favor one form of generation over another. The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, has called the proposal “a massive subsidy.” Other critics say the way to promote reliability and resilience in a competitive energy market is to create a new market for that service and let everyone bid to supply it.

What does FERC do?

FERC is an independent federal agency that regulates rates for cross-state transmission of our main energy sources: oil, natural gas and electricity. It also is responsible for reviewing siting for natural gas pipelines; creating and enforcing reliability standards for interstate electricity transmission networks; and monitoring and investigating energy markets. Most local aspects of the energy system, such as retail sales and billing, are typically overseen by state public utility commissions.

FERC also produces market reports, predictions and analyses of issues such as expected wholesale energy prices and the changing mix of power plants that supply our electricity. It has the power both to create and to enforce rules governing energy markets under its purview.

Who serves on the commission, and how are they chosen?

At full strength FERC has five commissioners, who are appointed by the president and approved by the Senate for five-year terms. It is designed to be a bipartisan independent agency, so no more than three commissioners can be from the same political party, and each commissioner has an equal vote in regulatory matters.

FERC and its commissioners are not overseen by the Department of Energy, but DOE can participate in its deliberations as a third party and can propose rules for the commission to consider.

Don’t states also regulate electricity prices?

FERC regulates interstate wholesale electricity markets, in which electricity crosses state lines. Retail prices, which are what most customers see on their bills, are regulated at the state level. Retail prices are set differently in different parts of the United States, and sometimes even within states. However, FERC’s wholesale pricing rules ultimately shape the prices that retail electricity suppliers are allowed to charge consumers.

For fully regulated areas, such as the Southeast, rates are proposed by utilities and then must gain approval from the state’s public utility commission. Some states have deregulated their electricity markets and allow customers to choose their power provider. In these areas, providers have more latitude to set their own rates, but the assumption is that market competition will keep rates low.

An Energy Department study on grid reliability, released in August, concluded that coal and nuclear power plants are struggling because they are being undercut by cheap natural gas and renewable energy and low growth in electricity demand. It also noted that “merchant” plants – those that compete based on price in deregulated states – accounted for a majority of recent early retirements. DOE’s proposal is limited to such plants, mainly in the Northeast and Midwest.

If FERC issues a rule that would subsidize coal and nuclear plants, can opponents do anything about it?

Opponents’ main recourse would be to sue in federal court. No lawsuits have been announced yet, and none is likely to be filed until FERC issues a decision. But a joint letter opposed to the proposal from a group of strange bedfellows, including the American Council on Renewable Energy, the American Petroleum Institute, the American Wind Energy Association and the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America, signals that resistance could be significant.

Joshua Rhodes abides by the disclosure policies of the University of Texas at Austin. The University of Texas at Austin is committed to transparency and disclosure of all potential conflicts of interest. He has filed all required financial disclosure forms with the university. Joshua Rhodes has not received any research funding that would create a conflict of interest or the appearance of such a conflict. In addition to research work on topics generally related to energy systems at the University of Texas at Austin, Joshua Rhodes is an equity partner in IdeaSmiths LLC, which consults on topics in the same areas of interests. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by the University of Texas at Austin in accordance with its policy on objectivity in research.

Read These Next

ICE not only looks and acts like a paramilitary force – it is one, and that makes it harder to curb

ICE, created in response to 9/11, meets most definitions of paramilitary forces. Critics worry it’s…

Not all mindfulness is the same – here’s why it matters for health and happiness

Mindfulness is taught everywhere, from schools to workplaces. But scientists define and measure it in…

It’s easy making green: Muppets continue to make a profit 50 years into their run

The most sensational, inspirational, celebrational and Muppetational show was originally rejected by…