Trump administration's zeal to peel back regulations is leading us to another era of robber barons

The Trump administration is committed to deregulating industry, as it's done with the EPA Clean Power Plan. But a historian shows how regulations have actually benefited both industry and consumers.

The Trump administration has a clear economic objective: deregulate. Loosening regulations on industries, the White House believes, will lead to faster growth and more jobs. This is the stated reason for pulling the U.S. from the international climate accord, and the economic justification for seeking to rescind the EPA Clean Power Plan that limits carbon emissions from plants.

But an examination of history shows that government regulations are not always harmful to industry; they often help business. Indeed, government regulation is as central to the growth of the American economy as markets and dollars.

Robber barons and the Progressive Era

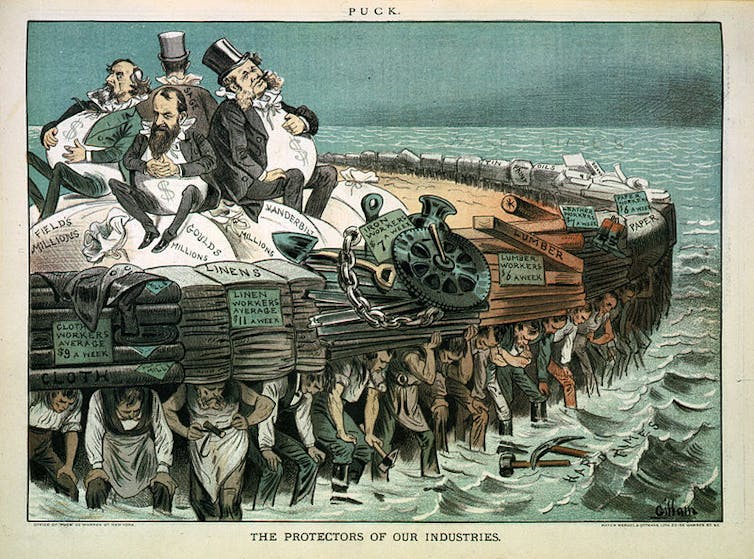

The late 19th century in the United States was the heyday of robber barons – John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Jay Gould and many others – who secured exorbitant wealth by building unregulated monopolies. They controlled the country’s oil, steel and railroads, and they used their wealth to bankrupt competitors, buy off politicians and fleece consumers. They manipulated a growing market economy that had weak rules and even weaker legal enforcement.

The progressive movement of the early 20th century took aim at the robber barons, calling upon government to regulate their activities in the interest of the public welfare. Writing on the eve of the First World War, journalist Walter Lippmann famously explained that Americans had a choice to continue their economic drift into ever-deeper corruption and inequality, or they could empower their elected representatives to master the challenges of their age and create a more just and sustainable economic order. Lippmann and other progressives wanted a more active government, led by men of intelligence, who would regulate the most powerful corporations and ensure that they served the public interest.

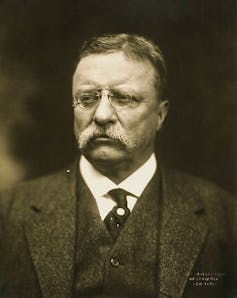

President Theodore Roosevelt was a creature of both the New York business elite from which he came and the progressive reform movement which he eloquently embraced with his calls for a “square deal” to help the poor and “strenuous” efforts by the well-endowed to enter “in the arena.” Roosevelt saw himself as part of an intelligent and energetic elite who would take the reins of government to improve society as a whole.

From the Executive Mansion, which he renamed the “White House,” Roosevelt pushed the federal government to expand its regulatory role over oil, steel, railroads and numerous other industries. He was not anti-business. His efforts proved that government regulation could improve the lives of citizens while allowing businesses to continue to prosper.

Historians of the period like me have, in fact, shown that the progressive era regulations often helped businesses by providing them with a more stable, predictable economic environment, where government regulations enabled increased capital investments and expanded consumer purchases. Progressive regulations of the robber baron market were good for businesses and consumers.

Regulatory ‘capture’

The same is true for regulations a century later. Government activities to ensure competition, transparency and safety in various industries give the American economy stability almost unparalleled in any other country.

Investors send their capital to American companies because government regulations ensure that capital is not stolen or siphoned for corrupt purposes. Talented workers travel to the United States to work in American companies because government regulations protect safe and humane working environments, where businesses are held accountable for fulfilling their obligations to employees. Consumers buy products from American businesses – from food and drink to cars and houses – confident that they are receiving value for their money because of government regulations against cheating, lying and fakery in product sales. Investors buy stocks in the auto companies, workers seek employment in the auto industry and citizens buy cars because government helps protect the integrity of the process at all levels. The federal government bails out shareholders, workers and purchasers when everything goes wrong.

This is not to say that all regulation is good. Sometimes regulation chokes innovation by slowing change and prohibiting risk taking. This was evidently true for regulated monopolies in mid-20th-century America, including the venerable Bell telephone company.

In other circumstances, regulations empower special interest groups who gain power from laws that protect them and hurt potential competitors. This is true for pharmaceutical and insurance companies who drive the massive and troubled health care industry in the United States today. Government regulations actually disempower doctors, who have reduced control over treatments, and patients, who cannot shop for price when they are choosing health options.

Extensive research shows that business leaders often “capture” regulation. Large companies – particularly in communications, real estate, pharmaceuticals and defense – use clever legal practices, control over information and often brute force to make regulators bend to their will.

The classic case is how lobbyists for Lockheed Martin, Boeing and other military contractors pressure members of Congress, with thousands of constituents employed in the industry, to limit restrictions on their production and sales. The regulators get bought off and bullied into becoming the advocates of the companies they are supposed to control.

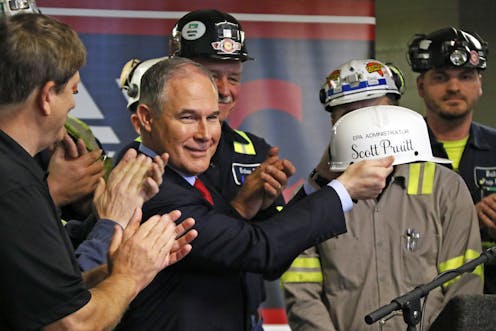

Perhaps college athletics is the best example. Does the NCAA really regulate the big college sports programs, or does it advocate for them, and defend them when they bend the rules? As for the fate of the Clean Power Plan, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt is an unabashed champion of the fossil fuel industry, declaring the “war on coal is over” when announcing plans to roll back regulations to limit carbon emissions from power plants.

Consumer benefits

This short history of government regulation shows how complex the issue really is.

The historical record reveals that regulation is generally beneficial to big established businesses: It often solidifies their dominance in markets, stabilizing basic practices. However, regulation will frequently hurt small startup competitors, who cannot mobilize as much influence over the regulators as their bigger counterparts. For consumers, regulation can help or hurt, depending on how it is carried out.

With the determined political leadership of a leader like Theodore Roosevelt, regulations can indeed make workplaces safer and products more reliable for citizens, while providing the stable conditions corporations need to do business. But vigilance is necessary, and a number of government boards and agencies emerged to play this role. Hence the creation of federal bodies from the Federal Communications Commission (1934) and the National Labor Relations Board (1935) to the Federal Aviation Administration (1958) and the Environmental Protection Agency (1970), and many others.

When we look forward to the next decade, the question is not whether to have federal regulations. Less regulation will only mean more instability, uncertainty and losses for businesses and consumers. The real question is what kind of regulations, and how can federal, state and local governments administer them to serve the public interest as a whole, preventing excessive red tape, special interest domination and big business “capture.”

What the United States needs is less ideology and more detailed attention among politicians to matching regulatory processes with public purposes. That was, of course, the goal of the progressives more than a century ago. If we don’t return to their model, chances are we will continue the current drift into another age of robber barons.

Jeremi Suri does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Read These Next

GLP-1 drugs may fight addiction across every major substance, according to a study of 600,000 people

GLP-1 drugs are the first medication to show promise for treating addiction to a wide range of substances.

Hezbollah − degraded, weakened but not yet disarmed − destabilizes Lebanon once again

Hezbollah’s entry into the current war followed the killing of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The group has…

Congress once fought to limit a president’s war powers − more than 50 years later, its successors ar

At the tail end of the Vietnam War, Congress engaged in a breathtaking act of legislative assertion,…