Urban noise pollution is worst in poor and minority neighborhoods and segregated cities

New research shows that noise pollution in US cities is concentrated in poor and minority communities. Beyond regulating airplane noise, the US has done relatively little to curb noise pollution.

Most Americans think of cities as noisy places – but some parts of U.S. cities are much louder than others. Nationwide, neighborhoods with higher poverty rates and proportions of black, Hispanic and Asian residents have higher noise levels than other neighborhoods. In addition, in more racially segregated cities, living conditions are louder for everyone, regardless of their race or ethnicity.

As environmental health researchers, we are interested in learning how everyday environmental exposures affect different population groups. In a new study we detail our findings on noise pollution, which has direct impacts on public health.

Scientists have documented that environmental hazards, such as air pollution and hazardous waste sites, are not evenly distributed across different populations. Often socially disadvantaged groups such as racial minorities, the poor and those with lower levels of educational attainment experience the highest levels of exposure. These dual stresses can represent a double jeopardy for vulnerable populations.

Our research shows that like air pollution, noise exposure may follow a similar social gradient. This unequal burden may, in part, contribute to observed health disparities across diverse groups in the United States and elsewhere.

Mapping city sounds

In 2015 we stumbled across a Smithsonian Magazine post about the National Park Service sound map. The sound estimates are meant to represent average noise levels during a summer day or night. They rely on 1.5 million hours of sound measurements across 492 locations, including urban areas and national forests, and modeling based on topography, climate and human activity. National Park Service colleagues shared their model and collaborated on our study.

By linking the noise model to national U.S. population data, we made some interesting discoveries. First, in both rural and urban areas, affluent communities were quieter. Neighborhoods with median annual incomes below US$25,000 were nearly 2 decibels louder than neighborhoods with incomes above $100,000 per year. And nationwide, communities with 75 percent black residents had median nighttime noise levels of 46.3 decibels – 4 decibels louder than communities with no black residents. A 10-decibel increase represents a doubling in loudness of a sound, so these are big differences.

Why worry about noise?

A growing body of evidence links noise from a variety of sources, including air, rail and road traffic, and industrial activity to adverse health outcomes. Studies have found that kids attending school in louder areas have more behavioral problems and perform worse on exams. Adults exposed to higher noise levels report higher levels of annoyance and sleep disturbances.

Scientists theorize that since evolution programmed the human body to respond to noises as threats, noise exposures activate our natural flight-or-fight response. Noise exposure triggers the release of stress hormones, which can raise our heart rates and blood pressure even during sleep. Long-term consequences of these reactions include high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and lower birth weight.

As with other types of pollution, multiple factors help explain why some social groups are more exposed to noise than others. Factors include weak enforcement of regulations in marginalized neighborhoods, lack of capacity to engage in land use decisions and environmental policies that fail to adequately protect vulnerable communities. This may lead to siting of noise generating industrial facilities, highways and airports in poorer communities.

Segregated communities are louder

We also found higher noise levels in more racially segregated metropolitan areas, such as Milwaukee, Chicago, Cleveland, Trenton and Memphis. This relationship affected all members of these communities. For example, noise levels in communities made up entirely of white Americans in the least segregated metropolitan areas were nearly 5 decibels quieter than all-white neighborhoods in the most segregated metropolitan areas.

Segregation in U.S. metropolitan areas is a process that spatially binds communities of color and working-class residents through the concentration of poverty, lack of economic opportunity, exclusionary housing development and discriminatory lending policies. But why would even all-white neighborhoods in highly segregated cities be noisier than those elsewhere? Although we did not find conclusive evidence, we believe this happens because in highly segregated cities, political power is often unequally distributed along racial, ethnic and economic lines.

These power differences may empower some residents to manage undesirable land uses in ways that are beneficial to them – for example, by forcing freeway construction through poorer communities. This scenario can lead to higher levels of environmental hazards overall than would occur if power and the burdens of development were more equally spread across the community.

Segregation can also physically separate neighborhoods, workplaces and basic services, forcing all residents to drive more and commute farther. These conditions can increase air pollution and, potentially, metro-wide noise levels for everyone.

Curbing noise pollution

The U.S. government has done relatively little to regulate noise levels since 1981, when Congress abruptly stopped funding the Noise Control Act of 1972. However, Congress did not repeal the law, so states had to assume responsibility for noise control. Few states have tried, and there has been scant progress. For example, in 2013-2014 New York City received one noise complaint about every four minutes.

Without funding, noise research has proven difficult. Until recently the United States did not even have up-to-date nationwide noise maps. In contrast, multiple European countries have mapped noise, and the European Commission funds noise communication plans, abatement and health studies.

In 2009 the World Health Organization released a report detailing nighttime noise guidelines for Europe. They recommended reducing noise levels when possible and reducing the impact of noise when levels could not be moderated. For example, the guidelines recommended locating bedrooms on the quiet sides of houses, away from street traffic, and keeping nighttime noise levels below 40 decibels to protect human health. The agency encouraged all member states to strive for these levels in the long term, with a short-term goal of 55 decibels at night.

Nonetheless, inequalities in exposure to noise still exist in Europe. For example, in Wales and Germany, poorer individuals have reported more neighborhood noise.

The most successful U.S. noise reduction efforts have centered on the airline industry. Driven by the introduction of new, more efficient and quieter engines and promoted by the Airport Noise and Capacity Act of 1990, the number of Americans affected by aviation noise declined by 95 percent between 1975 and 2000.

Moving forward, our findings suggest that more research is needed for studies on the relationship between noise and population health in the United States – data that could inform noise regulations. Funding and research should focus on poorer communities and communities of color that appear to bear a disproportionate burden of environmental noise.

Joan A. Casey receives funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the University of California at San Francisco Preterm Birth Initiative.

Peter James receives funding from the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Aging, and the Boston Nutrition Obesity Research Center.

Rachel Morello-Frosch receives funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, US EPA, the California Air Resources Board, the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, and the California Breast Cancer Research Program. She is affiliated with Grist as the board of directors chair and the Switzer Environmental Leadership Program as a board member.

Read These Next

CIA agents successfully executed a plan for regime change in Iran in 1953 – but Trump hasn’t reveale

A covert US campaign in the mid-20th century helped steer Iran toward the intense anti-American sentiment…

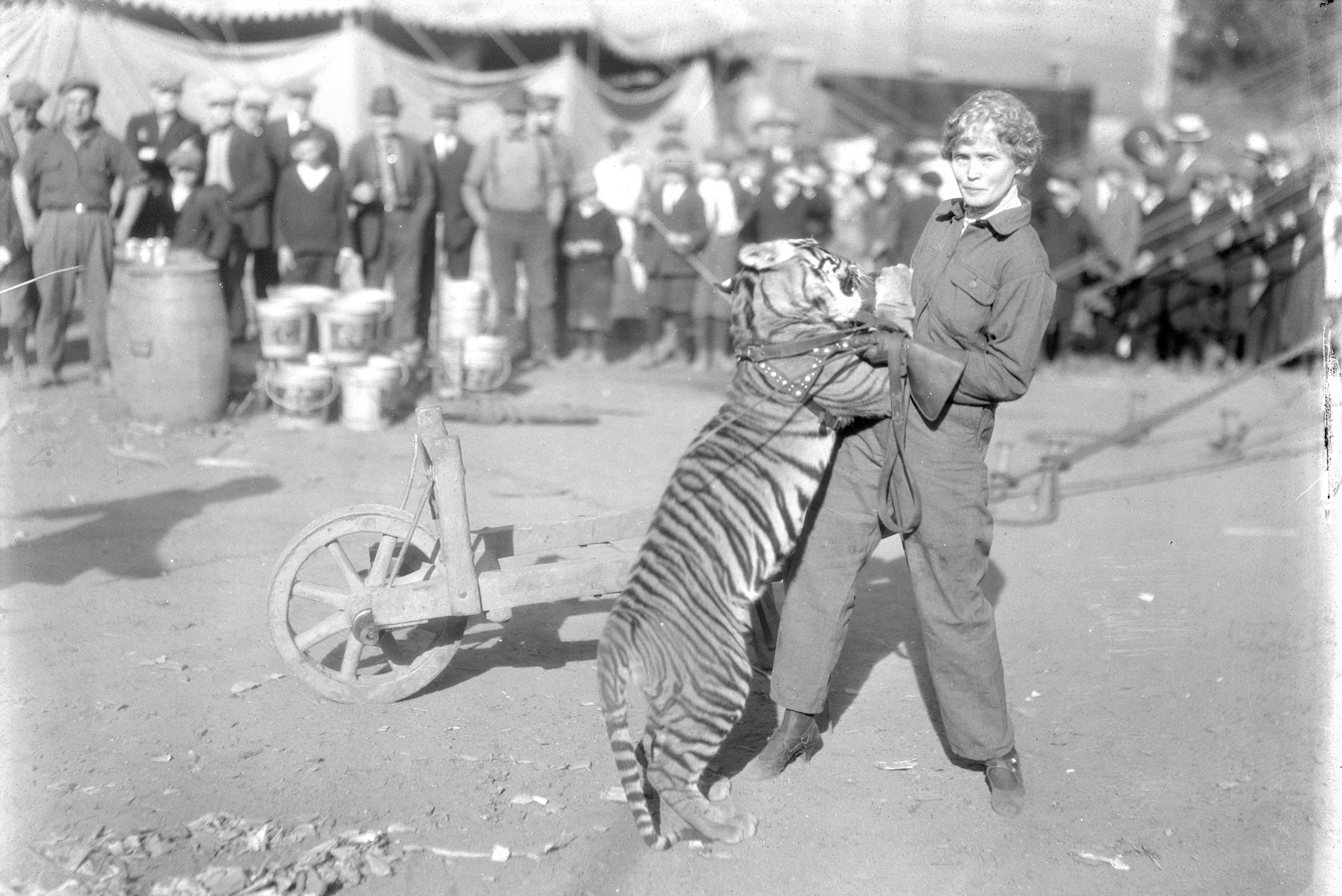

The inspiring and tragic story of Mabel Stark, America’s most famous female tiger trainer

Long before Joe Exotic became Tiger King, Mabel Stark reigned as Tiger Queen.

Formerly incarcerated Black men say they’re ‘doing OK’ while trying to cope with depression and PTSD

A nurse scientist interviewed 29 formerly incarcerated Black men in Philadelphia to understand…