The world is in water bankruptcy, UN scientists report – here’s what that means

Like living beyond your financial means, using more water than nature can replenish can have catastrophic results.

The world is now using so much fresh water amid the consequences of climate change that it has entered an era of water bankruptcy, with many regions no longer able to bounce back from frequent water shortages.

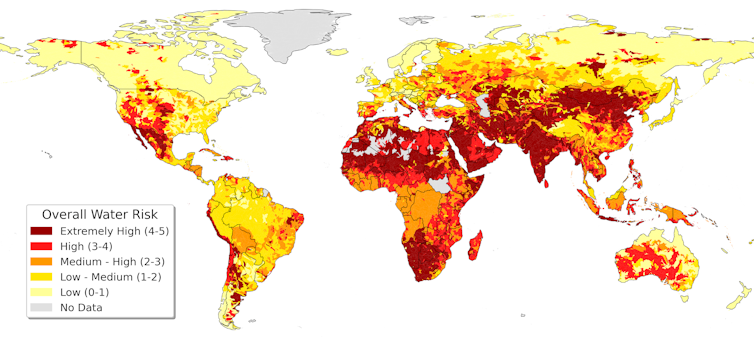

About 4 billion people – nearly half the global population – live with severe water scarcity for at least one month a year, without access to sufficient water to meet all of their needs. Many more people are seeing the consequences of water deficit: dry reservoirs, sinking cities, crop failures, water rationing and more frequent wildfires and dust storms in drying regions.

Water bankruptcy signs are everywhere, from Tehran, where droughts and unsustainable water use have depleted reservoirs the Iranian capital relies on, adding fuel to political tensions, to the U.S., where water demand has outstripped the supply in the Colorado River, a crucial source of drinking water and irrigation for seven states.

Water bankruptcy is not just a metaphor for water deficit. It is a chronic condition that develops when a place uses more water than nature can reliably replace, and when the damage to the natural assets that store and filter that water, such as aquifers and wetlands, becomes hard to reverse.

A new study I led with the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health concludes that the world has now gone beyond temporary water crises. Many natural water systems are no longer able to return to their historical conditions. These systems are in a state of failure – water bankruptcy.

What water bankruptcy looks like in real life

In financial bankruptcy, the first warning signs often feel manageable: late payments, borrowed money and selling things you hoped to keep. Then the spiral tightens.

Water bankruptcy has similar stages.

At first, we pull a little more groundwater during dry years. We use bigger pumps and deeper wells. We transfer water from one basin to another. We drain wetlands and straighten rivers to make space for farms and cities.

Then the hidden costs show up. Lakes shrink year after year. Wells need to go deeper. Rivers that once flowed year-round turn seasonal. Salty water creeps into aquifers near the coast. The ground itself starts to sink.

That last one, subsidence, often surprises people. But it’s a signature of water bankruptcy. When groundwater is overpumped, the underground structure, which holds water almost like a sponge, can collapse. In Mexico City, land is sinking by about 10 inches (25 centimeters) per year. Once the pores become compacted, they can’t simply be refilled.

The Global Water Bankruptcy report, published on Jan. 20, 2026, documents how widespread this is becoming. Groundwater extraction has contributed to significant land subsidence over more than 2.3 million square miles (6 million square kilometers), including urban areas where close to 2 billion people live. Jakarta, Bangkok and Ho Chi Minh City are among the well-known examples in Asia.

Agriculture is the world’s biggest water user, responsible for about 70% of the global freshwater withdrawals. When a region goes water bankrupt, farming becomes more difficult and more expensive. Farmers lose jobs, tensions rise and national security can be threatened.

About 3 billion people and more than half of global food production are concentrated in areas where water storage is already declining or unstable. More than 650,000 square miles (1.7 million square kilometers) of irrigated cropland are under high or very high water stress. That threatens the stability of food supplies around the world.

Droughts are also increasing in duration, frequency and intensity as global temperatures rise. Over 1.8 billion people – nearly 1 in 4 humans – dealt with drought conditions at various times from 2022 to 2023.

These numbers translate into real problems: higher food prices, hydroelectricity shortages, health risks, unemployment, migration pressures, unrest and conflicts.

How did we get here?

Every year, nature gives each region a water income, depositing rain and snow. Think of this like a checking account. This is how much water we receive each year to spend and share with nature.

When demand rises, we might borrow from our savings account. We take out more groundwater than will be replaced. We steal the share of water needed by nature and drain wetlands in the process. That can work for a while, just as debt can finance a wasteful lifestyle for a while.

Those long-term water sources are now disappearing. The world has lost more than 1.5 million square miles (4.1 million square kilometers) of natural wetlands over five decades. Wetlands don’t just hold water. They also clean it, buffer floods and support plants and wildlife.

Water quality is also declining. Pollution, saltwater intrusion and soil salinization can result in water that is too dirty and too salty to use, contributing to water bankruptcy.

Climate change is exacerbating the situation by reducing precipitation in many areas of the world. Warming increases the water demand of crops and the need for electricity to pump more water. It also melts glaciers that store fresh water.

Despite these problems, nations continue to increase water withdrawals to support the expansion of cities, farmland, industries and now data centers.

Not all water basins and nations are water bankrupt, but basins are interconnected through trade, migration, climate and other key elements of nature. Water bankruptcy in one area will put more pressure on others and can increase local and international tensions.

What can be done?

Financial bankruptcy ends by transforming spending. Water bankruptcy needs the same approach:

Stop the bleeding: The first step is admitting the balance sheet is broken. That means setting water use limits that reflect how much water is actually available, rather than just drilling deeper and shifting the burden to the future.

Protect natural capital – not just the water: Protecting wetlands, restoring rivers, rebuilding soil health and managing groundwater recharge are not just nice-to-haves. They are essential to maintaining healthy water supplies, as is a stable climate.

Use less, but do it fairly: Managing water demand has become unavoidable in many places, but water bankruptcy plans that cut supplies to the poor while protecting the powerful will fail. Serious approaches include social protections, support for farmers to transition to less water-intensive crops and systems, and investment in water efficiency.

Measure what matters: Many countries still manage water with partial information. Satellite remote sensing can monitor water supplies and trends, and provide early warnings about groundwater depletion, land subsidence, wetland loss, glacier retreat and water quality decline.

Plan for less water: The hardest part of bankruptcy is psychological. It forces us to let go of old baselines. Water bankruptcy requires redesigning cities, food systems and economies to live within new limits before those limits tighten further.

With water, as with finance, bankruptcy can be a turning point. Humanity can keep spending as if nature offers unlimited credit, or it can learn to live within its hydrological means.

Nothing to disclose.

Read These Next

Congress still has ways to throttle back Trump’s war with Iran – and to ask questions

As critics question President Trump’s motivations for war on Iran, it’s not just about politics.…

Patriots and loyalists both rallied around St. Patrick’s Day during the Revolutionary War

By the Revolutionary War in the late 1770s, those marking the anniversary of St. Patrick’s death on…

Indie coffee shops are meant to counter corporate behemoths like Starbucks – so why do they all look

The purportedly unique and local feel of coffee shops has instead been homogenized into a singular,…