Global power struggles over the ocean’s finite resources call for creative diplomacy

The expansion of Arctic shipping, scramble for seafloor mining and overfishing are all straining international relationships. But the powers of diplomacy go beyond ocean treaties.

Oceans shape everyday life in powerful ways. They cover 70% of the planet, carry 90% of global trade, and support millions of jobs and the diets of billions of people. As global competition intensifies and climate change accelerates, the world’s oceans are also becoming the front line of 21st-century geopolitics.

How policymakers handle these challenges will affect food supplies, the price of goods and national security.

Right now, international cooperation is under strain, but there are many ways to help keep the peace. The tools of diplomacy range from formal international agreements, like the High Seas Treaty for protecting marine life, which goes into effect on Jan. 17, 2026, to deals between countries, to efforts led by companies, scientists and issue-focused organizations.

Examples of each can be found in how the world is dealing with rising tensions over Arctic shipping, seafloor mining and overfishing. As researchers in international trade and diplomacy at Arizona State University in the Thunderbird School of Global Management’s Ocean Diplomacy Lab, we work with groups affected by ocean pressures like these to identify diplomatic tools – both inside and outside government – that can help avoid conflict.

Arctic shipping: New sea lanes, new risks

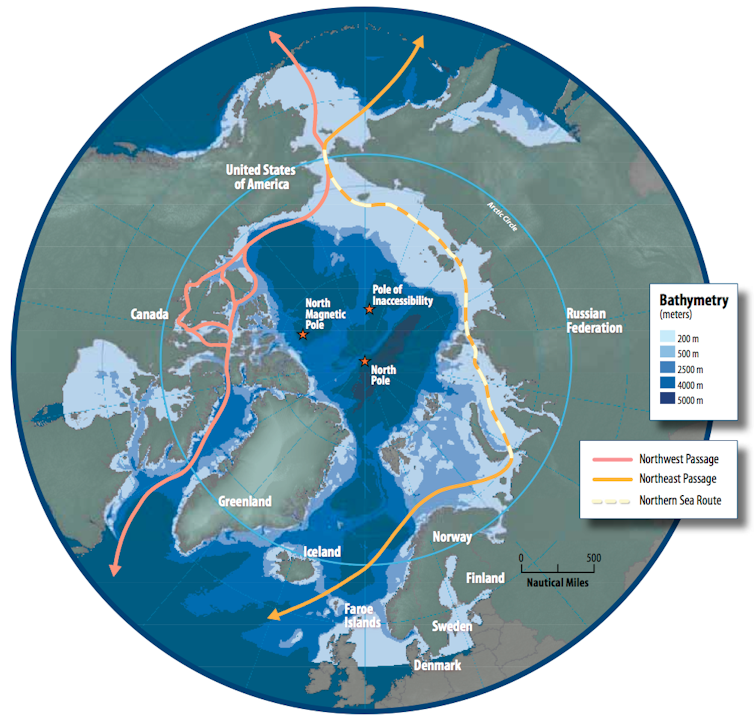

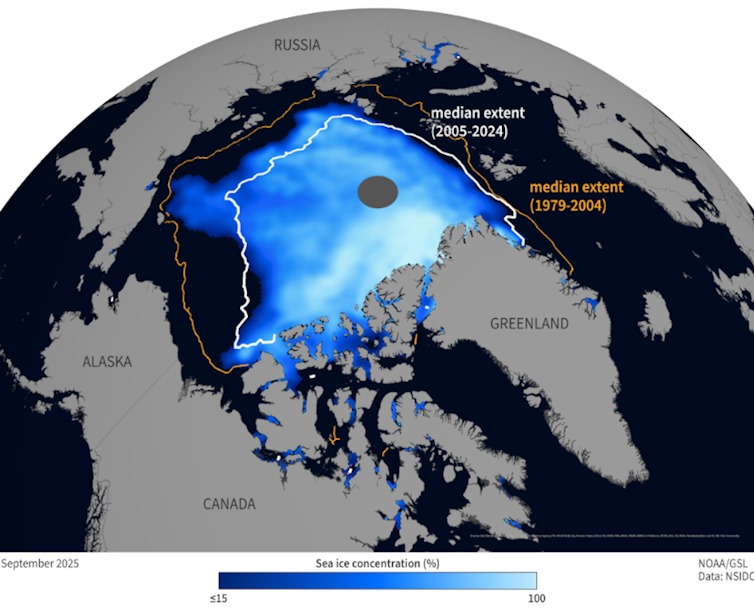

As the Arctic Ocean’s sea ice cover diminishes, shipping routes that were once impassable most of the year are opening up.

For companies, these routes – such as the Northern Sea Route along Russia’s coast and the Northwest Passage through Canada’s Arctic Archipelago – promise shorter transit times, lower fuel costs and fewer choke points than traditional passages.

However, Arctic shipping also raises complex challenges.

The U.S., Russia, China and several European countries have each taken steps to establish an economic and military presence in the Arctic Ocean, often with overlapping claims and competing strategic aims. For example, Russia closed off access to much of the Barents Sea while it conducted missile tests near Norway in 2025. NATO has also been patrolling the same sea.

Geopolitical tensions compound the practical dangers in Arctic waters that are poorly charted, where emergency response capacity is limited and where extreme weather is common.

As more commercial vessels move through these waters, a serious incident – whether triggered by a political confrontation or weather – could be difficult to contain and costly for marine ecosystems and global supply chains.

The Arctic Council is the region’s primary official forum for the Arctic countries to work together, but it is explicitly barred from addressing military and security issues – the very pressures now reshaping Arctic shipping.

The council went dormant for over a year starting in 2022 after Russia, then the Arctic Council president, invaded Ukraine. While meetings and projects involving the remaining countries have since resumed, the council’s influence has been undercut by unilateral moves by the Trump administration and Russia, and bilateral arrangements between countries, including Russia and China, often involving access to oil, gas and critical mineral deposits.

In this context, Arctic countries can strengthen cooperation through other channels. An important one is science.

For decades, scientists from the U.S., Europe, Russia and other countries collaborated on research related to public safety and the environment, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine disrupted those research networks.

Going forward, countries could share more data on ice thaw, extreme weather and emergency response to help prevent accidents in a rapidly opening shipping corridor.

Critical minerals: Control over the seabed

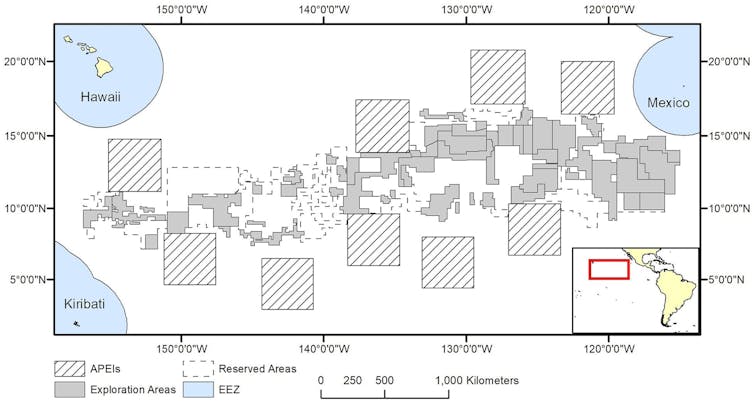

The global transition to clean energy is driving demand for critical minerals, such as nickel, cobalt, manganese and rare earth elements, that are essential for everything from smartphones and batteries to fighter jets. Some of the world’s largest untapped deposits lie deep below the ocean’s surface, in places like the Clarion-Clipperton Zone near Hawaii in the Pacific. This has sparked interest from governments and corporations in sea floor mining.

Harvesting critical minerals from the seabed could help meet demand at a time when China controls much of the global critical mineral supply. But deep-sea ecosystems are poorly understood, and disruptions from mining would have unknown consequences for ocean health. Forty countries now support either a ban or a pause on deep sea mining until the risks are better understood.

These concerns sit alongside geopolitical tensions: Most deep-sea minerals lie in international waters, where competition over access and profits could become another front in global rivalry.

The International Seabed Authority was created under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea to manage seabed resources, but its efforts to establish binding mining rules have stalled. The U.S. never ratified the convention, and the Trump administration is now trying to fast-track its own permits to circumvent the international process and accelerate deep-sea mining in areas that are outside national jurisdictions.

Against this backdrop, a loose coalition of issue-focused groups and companies have joined national governments in calling for a pause on deep-sea mining. At the same time, some insurers have declined to insure deep-sea mining projects.

Pressure from outside groups will not eliminate competition over seabed resources, but it can shape behavior by raising the costs of moving too quickly without carefully evaluating the risks. For example, Norway recently paused deep-sea mining licenses until 2029, while BMW, Volvo and Google have pledged not to purchase metals produced from deep-sea mines until environmental risks are better understood.

Overfishing: When competition outruns cooperation

Fishing fleets have been ranging farther and fishing longer in recent decades, leading to overfishing in many areas. For coastal communities, the result can crash fish stocks, threatening jobs in fishing and processing and degrading marine ecosystems, which makes coastal areas less attractive for tourism and recreation. When stocks decline, seafood prices also rise.

Unlike deep-sea mining or Arctic shipping, overfishing is prompting cooperation on many levels.

In 2025, a critical mass of countries ratified the High Seas Treaty, which sets out a legal framework for creating marine protected areas in international waters that could give species a chance to recover. Meanwhile, several countries have arrangements with their neighbors to manage fishing together.

For example, the European Union and U.K. are finalizing an agreement to set quotas for fleets operating in waters where fish stocks are shared. Likewise, Norway and Russia have established annual quotas for the Barents Sea to try to limit overfishing. These government-led efforts are reinforced by other forms of diplomacy that operate outside government.

Market-based initiatives like the Marine Stewardship Council certification set common sustainability standards for fishing companies to meet. Many major retailers look for that certification when making purchases. Websites like Global Fishing Watch monitor fishing activity in near real time, giving governments and advocacy groups data for action.

Collectively, these efforts make it harder for illegal fishing to hide.

How well countries are able to work together to update quotas, share data and enforce rules as warming oceans shift where fish stocks are found and demand continues to grow will determine whether overfishing can be stopped.

Looking Ahead

At a time when international cooperation is under strain, agreements between countries and pressure from companies, insurers and issue-focused groups are essential for ensuring a healthy ocean for the future.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Congress still has ways to throttle back Trump’s war with Iran – and to ask questions

As critics question President Trump’s motivations for war on Iran, it’s not just about politics.…

Patriots and loyalists both rallied around St. Patrick’s Day during the Revolutionary War

By the Revolutionary War in the late 1770s, those marking the anniversary of St. Patrick’s death on…

Indie coffee shops are meant to counter corporate behemoths like Starbucks – so why do they all look

The purportedly unique and local feel of coffee shops has instead been homogenized into a singular,…