US military has a long history in Greenland, from mining during WWII to a nuclear-powered Army base

History also shows that many of the fanciful engineering ideas for Greenland failed because they misjudged the island’s harsh climate and dynamic ice sheet.

President Donald Trump’s insistence that the U.S. will acquire Greenland “whether they like it or not” is just the latest chapter in a co-dependent and often complicated relationship between America and the Arctic’s largest island – one that stretches back more than a century.

Americans have long pursued policies in Greenland that U.S. leaders considered strategic and economic imperatives. As I recounted in my 2024 book, “When the Ice is Gone,” about Greenland’s environmental, military and scientific history, some of these ideas were little more than engineering fantasies, while others reflected unfettered military bravado.

But today’s world isn’t the same as when the United States last had a significant presence in Greenland, decades ago during the Cold War.

Before charging headlong into this icy island again, the U.S. would be remiss not to learn from past failures and consider how Earth’s rapidly changing climate is fundamentally altering the region.

Early US plundering of Greenland’s metals

In 1909, Robert Peary, a U.S. Navy officer, announced that he had won the race to the North Pole – a spectacular claim debated fiercely at the time. Before that, Peary had spent years exploring Greenland by dogsled, often taking what he found.

In 1894, he convinced six Greenlanders to come with him to New York, reportedly promising them tools and weapons in return. Within a few months, all but two of the Inuit had died from diseases.

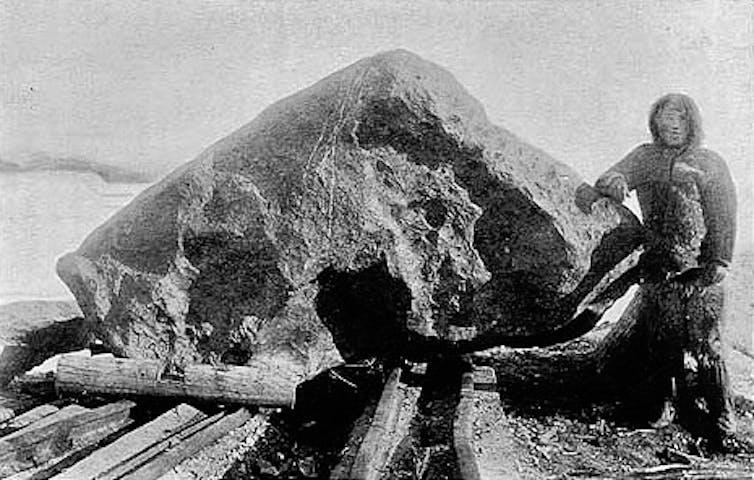

Peary also took three huge fragments of the Cape York iron meteorite, known to Greenlanders as Saviksoah. It was a unique source of metal that Greenlandic Inuit had used for centuries to make tools. The largest piece of the meteorite, Ahnighito, weighed 34 tons. Today, it sits in the American Museum of Natural History, which reportedly paid Peary US$40,000 for the space rocks.

World War II: Strategic location and minerals

World War II put Greenland on the map strategically for the U.S. military. In spring 1941, Denmark’s ambassador signed a treaty giving the U.S. military access to Greenland to help protect the island from Nazi Germany and contribute to the war effort in Europe. That treaty remains in effect today.

New American bases in western and southern Greenland became crucial refueling stops for planes flying from America to Europe.

Hundreds of American soldiers were garrisoned at Ivittuut, a remote town on the southern Greenland coast where they protected the world’s largest cryolite mine. The rare mineral was used for smelting aluminum, critical for building airplanes during the war.

And because Greenland is upwind from Europe, weather data collected on the island proved essential for battlefield forecasts as officers planned their moves during World War II.

Both the Americans and Germans built weather stations on Greenland, starting what historians refer to as the weather war. There was little combat, though allied patrols routinely scoured the east coast of the island for Nazi encampments. The weather war ended in 1944 when the U.S. Coast Guard, and its East Greenland dogsled patrol, found the last of four German weather stations and captured their meteorologists.

Cold War: Fanciful engineering ideas vs the ice

The heyday of U.S. military engineering dreams in Greenland arrived during the Cold War in the 1950s.

To counter the risk of Soviet missiles and bombers coming over the Arctic, the U.S. military transported about 5,000 men, 280,000 tons of supplies, 500 trucks and 129 bulldozers, according to The New York Times, to a barren, northwest Greenland beach – 930 miles (1,500 kilometers) from the North Pole and 2,752 miles (4,430 kilometers) from Moscow.

There, in one top-secret summer, they built the sprawling American air base at Thule. It housed bombers, fighters, nuclear missiles and more than 10,000 soldiers. The whole operation was revealed to the world the following year, on a September 1952 cover of LIFE magazine and by the U.S. Army in its weekly television show, “The Big Picture.”

But in the realm of ideas born out of paranoia, Camp Century and Project Iceworm were the pinnacle.

The U.S. Army built Camp Century, a nuclear-powered base, inside the ice sheet by digging deep trenches and then covering them with snow. The base held 200 men in bunkrooms heated to 72 degrees Fahrenheit (22 Celsius). It was the center of U.S. Army research on snow and ice and became a reminder to the USSR that the American military could operate at will in the Arctic.

The Army also imagined hundreds of miles of rail lines buried inside Greenland’s ice sheet. On Project Iceworm’s tracks, atomic-powered trains would move nuclear-tipped missiles in snow tunnels between hidden launch stations – a shell game covering an area about the size of Alabama.

In the end, Project Iceworm never got beyond a 1,300-foot (400-meter) tunnel the Army excavated at Camp Century. The soft snow and ice, constantly moving, buckled that track as the tunnel walls closed in. In the early 1960s, first the White House, and then NATO, rejected Project Iceworm.

In 1966, the Army abandoned Camp Century, leaving hundreds of tons of waste inside the ice sheet. Today, the crushed and abandoned camp lies more than 100 feet (30 meters) below the ice sheet surface. But as the climate warms and the ice melts, that waste will resurface: millions of gallons of frozen sewage, asbestos-wrapped pipes, toxic lead paint and carcinogenic PCBs.

Who will clean up the mess and at what cost is an open question.

Greenland remains a tough place to turn a profit

In the past, the American focus in Greenland was on short-term gains with little regard for the future. Abandoned bases, scattered around the island today and in need of cleanup, are one example. Peary’s disregard of the lives of local Greenlanders is another.

History shows that many of the fanciful ideas for Greenland failed because they showed little consideration of the island’s isolation, harsh climate and dynamic ice sheet.

Trump’s demands for American control of the island as a source of wealth and U.S. security are similarly shortsighted. In today’s rapidly warming climate, disregarding the dramatic effects of climate change in Greenland can doom projects to failure as Arctic temperatures climb.

Recent floods, fed by Greenland’s melting ice sheet, have swept away bridges that had stood for half a century. The permafrost that underlies the island is rapidly thawing and destabilizing infrastructure, including the critical radar installation and runway at Thule, renamed Pituffik Space Base in 2022. The island’s mountain sides are crashing into the sea as the ice holding them together melts.

The U.S. and Denmark have conducted geological surveys in Greenland and pinpointed deposits of critical minerals along the rocky, exposed coasts. However, most of the mining so far has been limited to cryolite and some small-scale extraction of lead, iron, copper and zinc. Today, only one small mine extracting the mineral anorthosite, which is useful for its aluminum and silica, is running.

It’s the ice that matters

The greatest value of Greenland for humanity is not its strategic location or potential mineral resources, but its ice.

If human activities continue to heat the planet, melting Greenland’s ice sheet, sea level will rise until the ice is gone. Losing even part of the ice sheet, which holds enough water to raise global sea level 24 feet in all, would have disastrous effects for coastal cities and island nations around the world.

That’s big-time global insecurity. The most forward-looking strategy is to protect Greenland’s ice sheet rather than plundering a remote Arctic island while ramping up fossil fuel production and accelerating climate change around the world.

Paul Bierman receives funding from the US National Science Foundation.

Read These Next

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…

Tiny recording backpacks reveal bats’ surprising hunting strategy

By listening in on their nightly hunts, scientists discovered that small, fringe-lipped bats are unexpectedly…

Bad Bunny says reggaeton is Puerto Rican, but it was born in Panama

Emerging from a swirl of sonic influences, reggaeton began as Panamanian protest music long before Puerto…