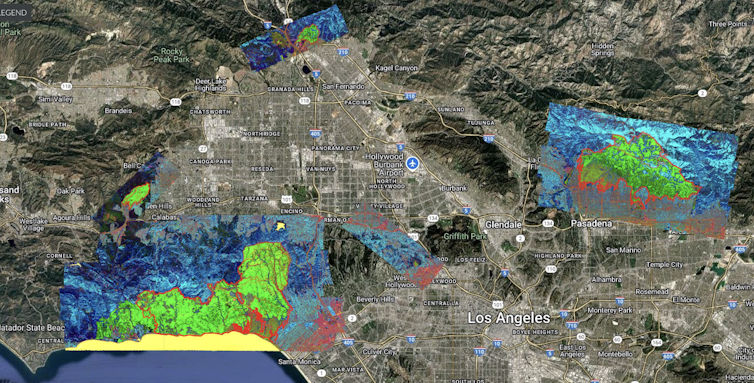

LA fire studies show the risks as wildfire smoke lingered inside homes

When cities burn, plastics, electronics, cleaning chemicals and much more create a toxic brew. Studies underway after the LA fires show exposure is often strongest inside homes.

When wildfires began racing through the Los Angeles area on Jan. 7, 2025, the scope of the disaster caught residents by surprise. Forecasters had warned about high winds and exceptionally dry conditions, but few people expected to see smoke and fires for weeks in one of America’s largest metro areas.

Environmental health scientist Yifang Zhu studies air quality at UCLA and began collecting samples from inside and outside homes the day after the fires began. In this Q&A, she describes findings by her team, a consortium of universities and local projects, that are painting a picture of the health risks millions of Los Angeles-area residents faced.

Their research offers both a warning and steps people everywhere can take to protect their homes and themselves from wildfire smoke in the future.

What made the LA fires unusual?

Urban fires are unique in a sense that it’s not just trees and other biomass burning. When homes and vehicles catch fire, plastics, electronics, cleaning chemicals, paints, textiles, construction material and much more burns, releasing chemicals and metals into the air.

More than 16,000 buildings burned in LA. Electric vehicles burned. A dental clinic burned. All of this gets mixed into the smoke in complicated ways, creating complex mixtures that can have definite health risks.

One thing we’ve found that is especially important for people to understand is that the concentration of these chemicals and metals can actually be higher inside homes compared with outside after a fire.

What are your health studies trying to learn?

To understand the health risks from air pollution, you need to know what people are exposed to and how much of it.

The LA Fire HEALTH Study, which I’m part of, is a 10-year project combining the work of exposure scientists and health researchers from several universities who are studying the long-term effects of the fire. Many other community and health groups are also working hard to help communities recover. A local program called CAP.LA, or Community Action Program Los Angeles, is supporting some of my work, including establishing a real-time air quality monitoring network in the Palisades area called CAP AIR.

During an active wildfire, it’s extremely difficult to collect high-quality air samples. Access is restricted, conditions change quickly, and research resources are often limited and take time to assemble. When the fires broke out not far from my lab at UCLA, my colleagues and I had been preparing for a different study and were able to quickly shift focus and start collecting samples to directly measure people’s exposure to metals and chemicals near and around the fires.

My group has been working with people whose homes were exposed to smoke but didn’t burn and collecting samples over time to understand the smoke’s effects. We’re primarily testing for volatile organic compounds off-gassing from soft goods – things like pillows, textiles and stuffed animals that are likely to absorb compounds from the smoke.

Our testing found volatile organic compounds that were at high levels outdoors during the active fire were still high indoors in February, after the fires were contained. When a Harvard University team led by environmental scientist Joe Allen took samples in March and April, they saw a similar pattern, with indoor levels still high.

What health risks did your team find in homes?

We have found high levels of different kinds of volatile organic compounds, which have different health risks. Some are carcinogens, like benzene. We have also found metals like arsenic, a known carcinogen, and lead, which is a neurotoxin.

Mike Kleeman, an air quality engineer at the University of California Davis, found elevated levels of hexavalent chromium in the nanometer-size range, which can be a really dangerous carcinogen. In March, he drove around collecting air samples from a burn zone. That was testing which government agencies would not have routinely done.

Fires have a long list of toxic compounds, and many of them aren’t being measured.

What do you want people to take away from these results?

People are exposed to many types of volatile organic compounds in their daily lives, but after wildfires, the indoor VOC levels can be much, much higher.

I think that’s a big public health message from the LA fires that people really need to know.

In general, people tend to think the outdoor air is worse for their health, particularly in a place like LA, but often, the indoor air is less healthy because there are several chemical emission sources right there and it’s an enclosed space.

Think about cooking with a gas stove, or burning candles or spraying air fresheners. All of these are putting pollutants into the air. Indoor pollution sources like cleaning fluids and PFAS from furniture and carpets are all around.

We often hear from people who are really worried about the air quality outside and its health risk during fires, but you need to think about the air indoors too.

What are some tips for people dealing with fires?

The LA fires have given us lots of insights into how to restore homes after smoke damage and what can be cleaned up, or remediated. One thing we want to do is develop an easy-to-follow decision tree or playbook that can help guide future fire recovery.

When the fires broke out, even I had to think about the actions I should take to reduce the smoke’s potential impact, and I study these risks.

First, close all your windows during the wildfire. If you have electricity, keep air purifiers running. That could help capture smoke that does get into the home before it soaks into soft materials.

Once the outside air is clean enough, then open those windows again to ventilate the house. Be sure to clean your HVAC system and replace filters, because the smoke leaves debris. If the home is severely impacted by smoke, some items will have to be removed, but not in every case.

And you definitely need to do testing. A home might seem fine when you look at it, but our testing showed how textiles and upholstery inside can continue off-gassing chemicals for weeks or longer.

But many people don’t have their homes tested after wildfires. They might not know how to read the results or trust the results. Remediation can also be expensive, and some insurance companies won’t cover it. There are probably people who don’t know whether their homes are safe at this point.

So there needs to be a clear path for recovery, with contamination levels to watch for and advice for finding help.

This is not going to be the last fire in the Los Angeles area, and LA will not be the last city to experience fire.

Yifang Zhu is working with CAP.LA (Community Action Project Los Angeles), which is funded by the R&S Kayne Foundation, and the LA Fire Health Study, which is funded by private philanthropists, including the Speigel Family Fund. Her work has also been partially funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Danhakl Family Foundation, and the California Air Resources Board.

Read These Next

Fat cells burn energy to make heat – making them the next frontier of weight loss therapies

GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy aid in weight loss by suppressing appetite. Researchers are looking…

AI doesn’t ‘see’ the way that you do, and that could be a problem when it categorizes objects and sc

People and computers perceive the world differently, which can lead AI to make mistakes no human would.…

Generative AI can play a role uplifting family and community in early childhood education

Researchers use text and image generators to design culturally relevant educational content for young…