Where the wild things thrive: Finding and protecting nature’s climate change safe havens

Protecting places that are likely to remain cool and moist as global temperatures rise can save wildlife of all kinds, but first we have to find them.

The idea began in California’s Sierra Nevada, a towering spine of rock and ice where rising temperatures and the decline of snowpack are transforming ecosystems, sometimes with catastrophic consequences for wildlife.

The prairie-doglike Belding’s ground squirrel (Urocitellus beldingi) had been struggling there as the mountain meadows it relies on dry out in years with less snowmelt and more unpredictable weather. At lower elevations, the foothill yellow-legged frog (Rana boylii) was also being hit hard by rising temperatures, because it needs cool, shaded streams to breed and survive.

As we studied these and other species in the Sierra Nevada, we discovered a ray of hope: The effects of warming weren’t uniform.

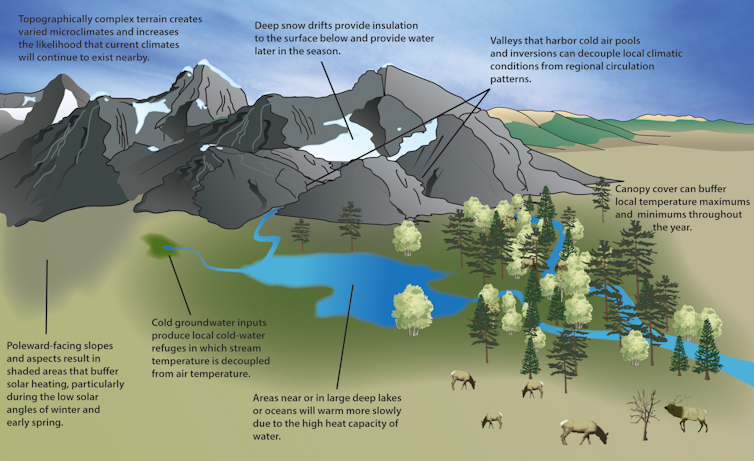

We were able to locate meadows that are less vulnerable to climate change, where the squirrels would have a better chance of thriving. We also identified streams that would stay cool for the frogs even as the climate heats up. Some are shaded by tree canopy. Others are in valleys with cool air or near deep lakes or springs.

These special areas are what we call climate change refugia.

Identifying these pockets of resilient habitat – a field of research that was inspired by our work with natural resource managers in the Sierra Nevada – is now helping national parks and other public and private land managers to take action to protect these refugia from other threats, including fighting invasive species and pollution and connecting landscapes, giving threatened species their best chance for survival in a changing climate.

Across the world, from the increasingly fire-prone landscapes of Australia to the glacial ecosystems at the southern tip of Chile, researchers, managers and local communities are working together to find and protect similar climate change refugia that can provide pockets of stability for local species as the planet warms.

A new collection of scientific papers examines some of the most promising examples of climate change refugia conservation. In that collection, over 100 scientists from four continents explain how frogs, trees, ducks and lions stand to benefit when refugia in their habitats are identified and safeguarded.

Saving songbirds in New England

The study of climate change refugia – places that are buffered from the worst effects of global warming – has grown rapidly in recent years.

In New England, managers at national parks and other protected areas were worried about how species are being affected by changes in climate and habitat. For example, the grasshopper sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum), a little grassland songbird that nests in the open fields in the eastern U.S. and southern Canada, appears to be in trouble.

We studied its habitats and projected that less than 6% of its summer northeastern U.S. range will have the right temperature and precipitation conditions by 2080.

The loss of songbirds is not only a loss of beauty and music. These birds eat insects and are important to the balance of the ecosystem.

The sand plain grasslands that the grasshopper sparrow relies on in the northeastern U.S. are under threat not only from changes in climate but also changes in how people use the land. Public land managers in Montague, Massachusetts, have used burning and mowing to maintain habitat for nesting grasshopper sparrows. That effort also brought back the rare frosted elfin butterfly for the first time in decades.

Protecting Canada’s vast forest ecosystems

In Canada, the climate is warming at about twice the global average, posing a threat to its vast forested landscapes, which face intensifying drought, insect outbreaks and destructive wildfires.

We have been actively mapping refugia in British Columbia, looking for shadier, wetter or more sheltered places that naturally resist the worst effects of climate change.

The mapping project will help to identify important habitat for wildlife such as moose and caribou. Knowing where these climate change refugia are allows land-use planners and Indigenous communities to protect the most promising habitats from development, resource extraction and other stressors.

British Columbia is undertaking major changes to forest landscape planning in partnership with First Nations and communities.

Lions, giraffes and elephants (oh, my!)

On the sweeping vistas of East Africa, dozens of species interact in hot spots of global biodiversity. Unfortunately, rising temperatures, prolonged drought and shifting seasons are threatening their very existence.

In Tanzania, working with government agencies and conservation groups through past USAID funding, we mapped potential refugia for iconic savanna species including lions, giraffes and elephants. These areas include places that will hold water in drought and remain cooler during heat waves. The iconic Serengeti National Park, home to some of the world’s most famous wildlife, emerged as a key location for climate change refugia.

Combining local knowledge with spatial analysis is helping prioritize areas where big cats, antelope, elephants and the other great beasts of the Serengeti ecosystem can continue to thrive – provided other, nonclimate threats such as habitat loss and overharvesting are kept at bay.

The Tanzanian government has already been working with U.S.-funded partners to identify corridors that can help connect biodiversity hot spots.

Hope for the future

By identifying and protecting the places where species can survive the longest, we can buy crucial decades for ecosystems while conservation efforts are underway and the world takes steps to slow climate change.

Across continents and climates, the message is the same: Amid our rapidly warming world, pockets of resilience remain for now. With careful science and strong partnerships, we can find climate change refugia, protect them and help the wild things continue to thrive.

Toni Lyn Morelli receives funding from U.S. Geological Survey.

Diana Stralberg receives funding from Natural Resources Canada, the Governments of the Northwest Territories and British Columbia, Canada, and the Wilburforce Foundation.

Read These Next

AI’s growing appetite for power is putting Pennsylvania’s aging electricity grid to the test

As AI data centers are added to Pennsylvania’s existing infrastructure, they bring the promise of…

Why US third parties perform best in the Northeast

Many Americans are unhappy with the two major parties but seldom support alternatives. New England is…

The cost of casting animals as heroes and villains in conservation science

New research shows how these storytelling choices can distort science – and how to move beyond them.