The North Pole keeps moving – here’s how that affects Santa’s holiday travel and yours

There are actually two North Poles. One has been wandering over northern Canada and north of there for years. An earth scientist explains why and what it means for holiday travel.

When Santa is done delivering presents on Christmas Eve, he must get back home to the North Pole, even if it’s snowing so hard that the reindeer can’t see the way.

He could use a compass, but then he has a challenge: He has to be able to find the right North Pole.

There are actually two North Poles – the geographic North Pole you see on maps and the magnetic North Pole that the compass relies on. They aren’t the same.

The two North Poles

The geographic North Pole, also called true north, is the point at one end of the Earth’s axis of rotation.

Try taking a tennis ball in your right hand, putting your thumb on the bottom and your middle finger on the top, and rotating the ball with the fingers of your left hand. The place where the thumb and middle finger of your right hand contact the tennis ball as it spins define the axis of rotation. The axis extends from the south pole to the north pole as it passes through the center of the ball.

Earth’s magnetic North Pole is different.

Over 1,000 years ago, explorers began using compasses, typically made with a floating cork or piece of wood with a magnetized needle in it, to find their way. The Earth has a magnetic field that acts like a giant magnet, and the compass needle aligns with it.

The magnetic North Pole is used by devices such as smartphones for navigation – and that pole moves around over time.

Why the magnetic north pole moves around

The movement of the magnetic North Pole is the result of the Earth having an active core. The inner core, starting about 3,200 miles below your feet, is solid and under such immense pressure that it cannot melt. But the outer core is molten, consisting of melted iron and nickel.

Heat from the inner core makes the molten iron and nickel in the outer core move around, much like soup in a pot on a hot stove. The movement of the iron-rich liquid induces a magnetic field that covers the entire Earth.

As the molten iron in the outer core moves around, the magnetic North Pole wanders.

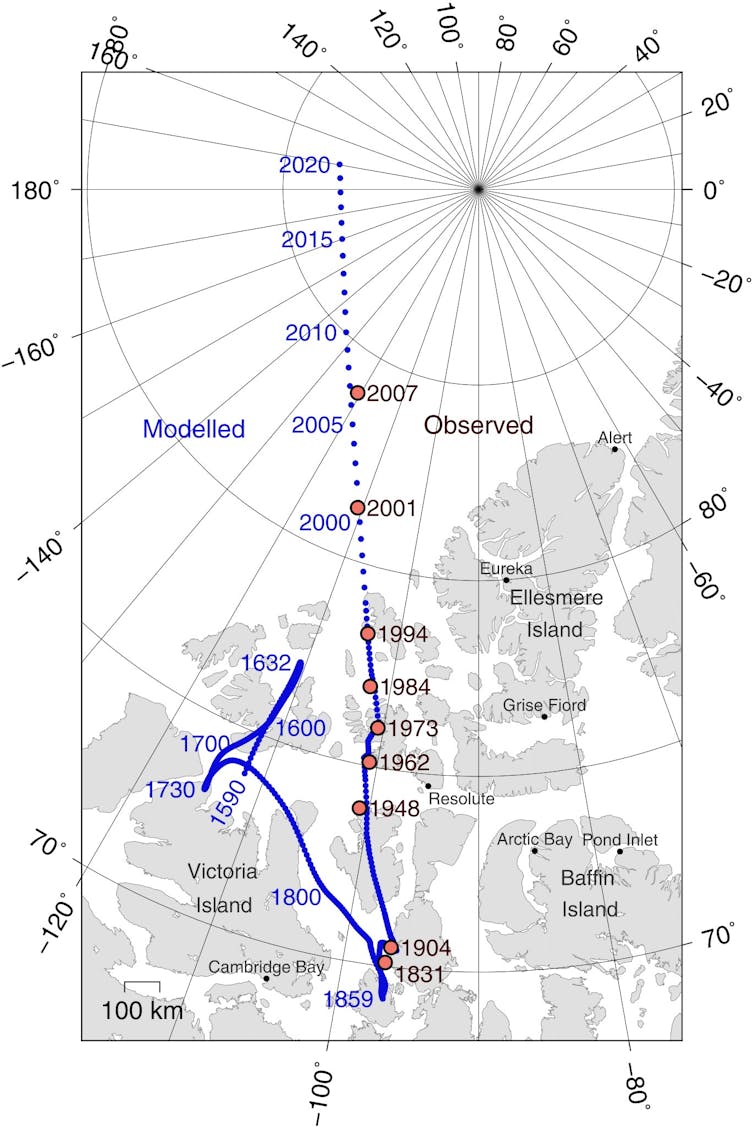

For most of the past 600 years, the pole has been wandering around over northern Canada. It was moving relatively slowly, around 6 to 9 miles per year, until around 1990, when its speed increased dramatically, up to 34 miles per year.

It started moving in the general direction of the geographic North Pole about a century ago. Earth scientists cannot say exactly why other than that it reflects a change in flow within the outer core.

Getting Santa home

So, if Santa’s home is the geographic North Pole – which, incidentally, is in the ice-covered middle of the Arctic Ocean – how does he correct his compass bearing if the two North Poles are in different locations?

No matter what device he might be using – compass or smartphone – both rely on magnetic north as a reference to determine the direction he needs to move.

While modern GPS systems can tell you precisely where you are as you make your way to grandma’s house, they cannot accurately tell which direction to go without your device knowing the direction of magnetic north.

If Santa is using an old-fashioned compass, he’ll need to adjust it for the difference between true north and magnetic north. To do that, he needs to know the declination at his location – the angle between true north and magnetic north – and make the correction to his compass. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has an online calculator that can help.

If you are using a smartphone, your phone has a built-in magnetometer that does the work for you. It measures the Earth’s magnetic field at your location and then uses the World Magnetic Model to correct for precise navigation.

Whatever method Santa uses, he may be relying on magnetic north to find his way to your house and back home again. Or maybe the reindeer just know the way.

Scott Brame does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Probability underlies much of the modern world – an engineering professor explains how it actually w

Scientific research, artificial intelligence and modern bank security all rely on probability.

Last nuclear weapons limits expired – pushing world toward new arms race

The expiration of the New START treaty has the US and Russia poised to increase the number of their…

Why Michelangelo’s ‘Last Judgment’ endures

The artist used daring imagery that sparked controversy from the moment it was unveiled.