Sea level doesn’t rise at the same rate everywhere – we mapped where Antarctica’s ice melt would hav

Understanding what happens to Antarctica’s ice matters, because as it melts, sea levels rise, affecting lives and economies around the world.

When polar ice sheets melt, the effects ripple across the world. The melting ice raises average global sea level, alters ocean currents and affects temperatures in places far from the poles.

But melting ice sheets don’t affect sea level and temperatures in the same way everywhere.

In a new study, our team of scientists investigated how ice melting in Antarctica affects global climate and sea level. We combined computer models of the Antarctic ice sheet, solid Earth and global climate, including atmospheric and oceanic processes, to explore the complex interactions that melting ice has with other parts of the Earth.

Understanding what happens to Antarctica’s ice matters, because it holds enough frozen water to raise average sea level by about 190 feet (58 meters). As the ice melts, it becomes an existential problem for people and ecosystems in island and coastal communities.

Changes in Antarctica

The extent to which the Antarctic ice sheet melts will depend on how much the Earth warms. And that depends on future greenhouse gas emissions from sources including vehicles, power plants and industries.

Studies suggest that much of the Antarctic ice sheet could survive if countries reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in line with the 2015 Paris Agreement goal to keep global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) compared to before the industrial era. However, if emissions continue rising and the atmosphere and oceans warm much more, that could cause substantial melting and much higher sea levels.

Our research shows that high emissions pose risks not just to the stability of the West Antarctic ice sheet, which is already contributing to sea-level rise, but also for the much larger and more stable East Antarctic ice sheet.

It also shows how different regions of the world will experience different levels of sea-level rise as Antarctica melts.

Understanding sea-level change

If sea levels rose like the water in a bathtub, then as ice sheets melt, the ocean would rise by the same amount everywhere. But that isn’t what happens.

Instead, many places experience higher regional sea-level rise than the global average, while places close to the ice sheet can even see sea levels drop. The main reason has to do with gravity.

Ice sheets are massive, and that mass creates a strong gravitational pull that attracts the surrounding ocean water toward them, similar to how the gravitational pull between Earth and the Moon affects the tides.

As the ice sheet shrinks, its gravitational pull on the ocean declines, leading to sea levels falling in regions close to the ice sheet coast and rising farther away. But sea-level changes are not only a function of distance from the melting ice sheet. This ice loss also changes how the planet rotates. The rotation axis is pulled toward that missing ice mass, which in turn redistributes water around the globe.

2 factors that can slow melting

As the massive ice sheet melts, the solid Earth beneath it rebounds.

Underneath the bedrock of Antarctica is Earth’s mantle, which flows slowly like maple syrup. The more the ice sheet melts, the less it presses down on the solid Earth. With less weight on it, the bedrock can rebound. This can lift parts of the ice sheet out of contact with warming ocean waters, slowing the rate of melting. This happens quicker in places where the mantle flows faster, such as underneath the West Antarctic ice sheet.

This rebound effect could help preserve the ice sheet – if global greenhouse gas emissions are kept low.

Another factor that can slow melting might seem counterintuitive.

While Antarctic meltwater drives rising sea levels, models show it also delays greenhouse gas-induced warming. That’s because icy meltwater from Antarctica reduces ocean surface temperatures in the Southern Hemisphere and tropical Pacific, trapping heat in the deep ocean and slowing the rise of global average air temperature.

But as melting occurs, even if it slows, sea levels rise.

Mapping our sea-level results

We combined computer models that simulate these and other behaviors of the Antarctic ice sheet, solid Earth and climate to understand what could happen to sea level around the world as global temperatures rise and ice melts.

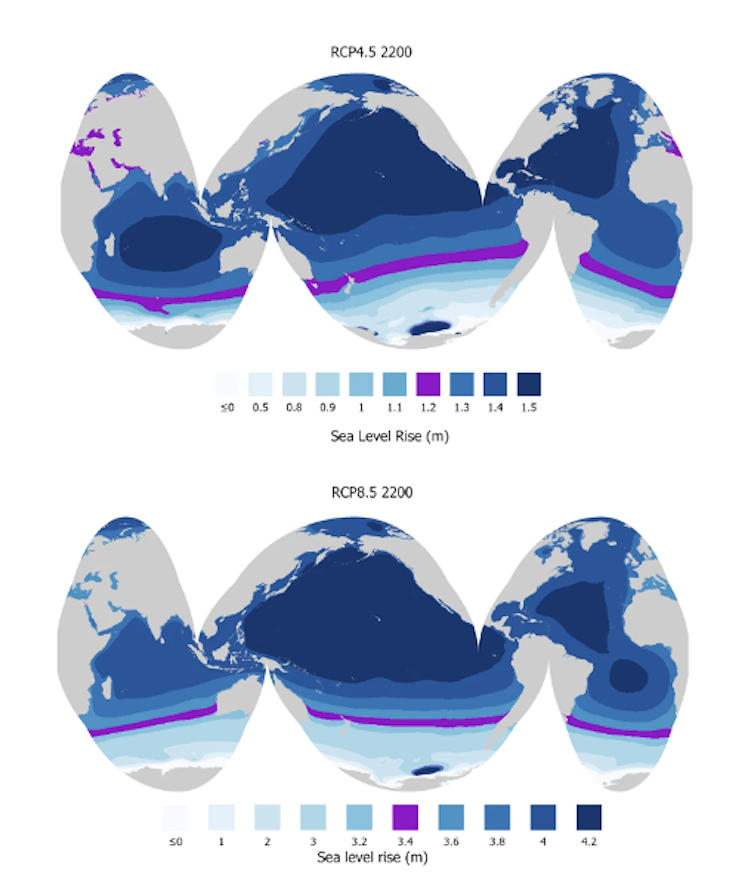

For example, in a moderate scenario in which the world reduces greenhouse gas emissions, though not enough to keep global warming under 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) in 2100, we found the average sea-level rise from Antarctic ice melt would be about 4 inches (0.1 meters) by 2100. By 2200, it would be more than 3.3 feet (1 meter).

Keep in mind that this is only sea-level rise caused by Antarctic melt. The Greenland ice sheet and thermal expansion of seawater as the oceans warm will also raise sea levels. Current estimates suggest that total average sea-level rise – including Greenland and thermal expansion – would be 1 to 2 feet (0.32 to 0.63 meters) by 2100 under the same scenario.

We also show how sea-level rise from Antarctica varies around the world.

In that moderate emissions scenario, we found the highest sea-level rise from Antarctic ice melt alone, up to 5 feet (1.5 meters) by 2200, occurs in the Indian, Pacific and western Atlantic ocean basins – places far from Antarctica.

These regions are home to many people in low-lying coastal areas, including residents of island nations in the Caribbean, such as Jamaica, and the central Pacific, such as the Marshall Islands, that are already experiencing detrimental impacts from rising seas.

Under a high emissions scenario, we found the average sea-level rise caused by Antarctic melting would be much higher: about 1 foot (0.3 meters) in 2100 and close to 10 feet (more than 3 meters) in 2200.

Under this scenario, a broader swath of the Pacific Ocean basin north of the equator, including Micronesia and Palau, and across the middle of the Atlantic Ocean basin would see the highest sea-level rise, up to 4.3 meters (14 feet) by 2200, just from Antarctica.

Although these sea-level rise numbers seem alarming, the world’s current emissions and recent projections suggest this very high emissions scenario is unlikely. This exercise, however, highlights the serious consequences of high emissions and underscores the importance of reducing emissions.

The takeaway

These impacts have implications for climate justice, particularly for island nations that have done little to contribute to climate change yet already experience the devastating impacts of sea-level rise.

Many island nations are already losing land to sea-level rise, and they have been leading global efforts to minimize temperature rise. Protecting these countries and other coastal areas will require reducing greenhouse gas emissions faster than nations are committing to do today.

Shaina Sadai has received funding from the National Science Foundation and the Hitz Family Foundation.

Ambarish Karmalkar receives funding from National Science Foundation.

Read These Next

Will AI accelerate or undermine the way humans have always innovated?

An anthropologist’s new book lays out the formula for human innovation, from stone tools to supercomputers.…

Fewer new moms are dying in Colorado – naloxone might be one reason why

The opioid reversal drug is distributed directly to new moms at many of Colorado’s birthing hospitals.

How to prevent elections from being stolen − lessons from around the world for the US

As President Trump and other Republicans cast doubt on the legitimacy of the US electoral system, other…