For many in Puerto Rico, 'energy dominance' is just a new name for US colonialism

In Puerto Rico the Trump administration's 'energy dominance' policy echoes colonial practices by fast-forwarding fossil fuel projects over community resistance.

The Trump administration has made “achieving American energy dominance” a central policy goal. President Trump asserts that “energy dominance” requires expanding nuclear development, increasing coal and natural gas exports, building transnational pipelines and accessing offshore oil and gas deposits. These efforts, Trump contends, will maximize the nation’s “boundless capacity” for energy production, including spreading U.S. fossil fuels around the globe, to showcase its independence from foreign oil.

My research studies how expansionist efforts play out in the U.S. unincorporated territory of Puerto Rico. For centuries, Spanish and U.S. colonial governments and corporations have practiced what could be called “energy dominance” by harnessing human labor and fossil fuels to exploit local resources through mining, coffee and sugarcane development, and other industries. Puerto Rico’s history makes clear that Trump’s policy, which benefits corporations and their political allies to the detriment of local communities, promises more of the same.

Fueling energy colonialism

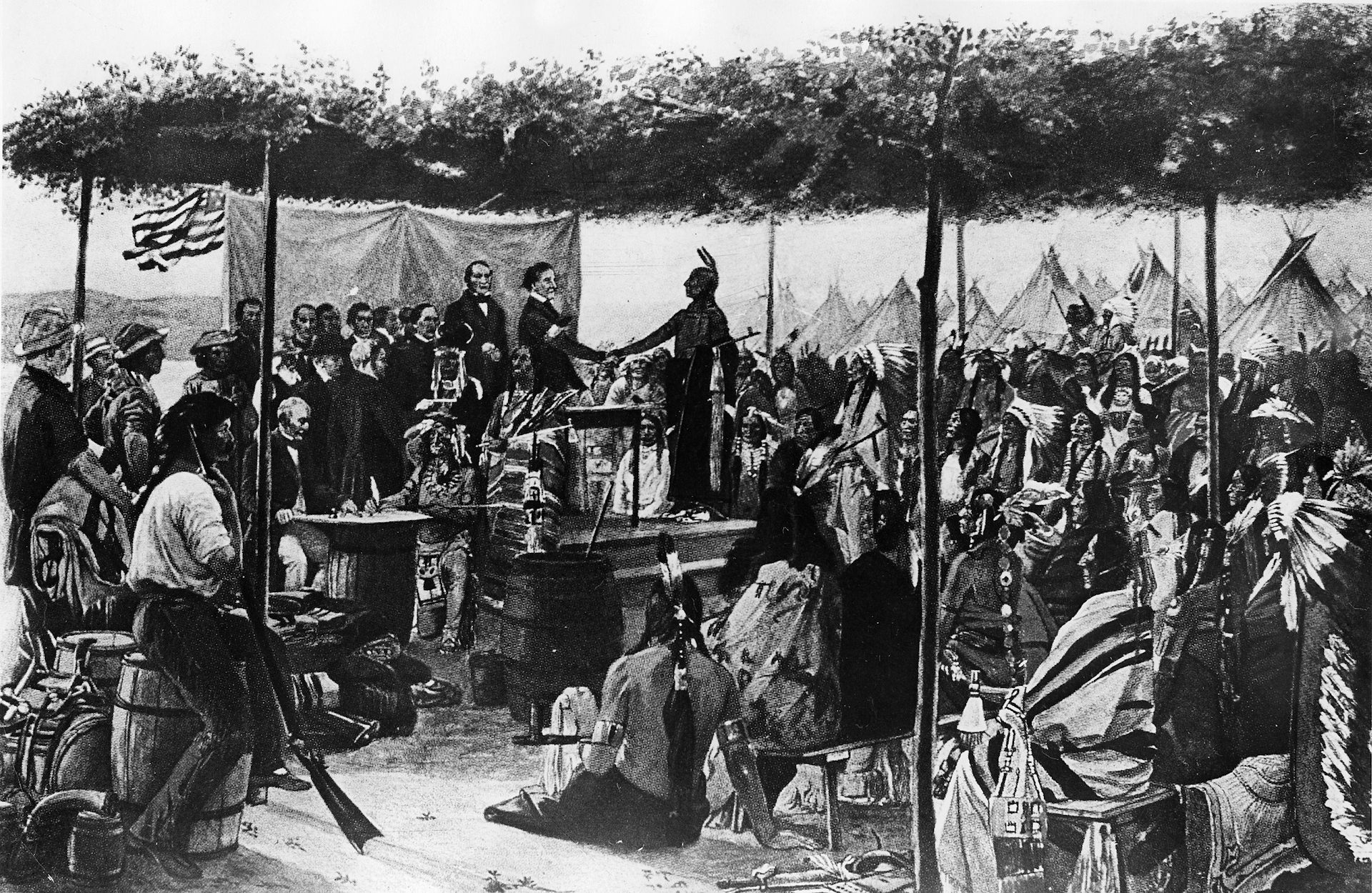

The United States seized control of Puerto Rico in 1898. Like other imperial powers, the United States justified exploiting other people and places by portraying them as backward and promising to modernize them.

Many U.S. government officials, legal experts, researchers and artists assumed that colonized peoples were inferior. In their view, African and indigenous ancestries and prior colonization by Spain marked people who lived in the newly acquired “possessions” as primitive, childlike and weak.

In his 1899 book “Our Islands and Their People,” writer and diplomat José de Olivares stated,

“Without our fostering benevolence, this island [Puerto Rico] would be as unhappy and prostrate as are some of the neighboring British, French, Dutch, and Danish islands.”

During this same period, Supreme Court justices described U.S. colonies as home to “uncivilized” and “savage” “alien races.” Racist claims of U.S. superiority and goodwill drove colonial policy and relationships of dependency.

Locked into fossil fuel

U.S. imperial ambitions prompted politicians to position Puerto Rico as a showcase for capitalism in Latin America. In the 1940s Puerto Rican Governor Luis Muñoz Marín and U.S. government officials implemented a massive industrialization plan called Operation Bootstrap.

The program used tax breaks, duty-free trade, exploitable local labor, natural resources and cheap foreign crude oil and electricity prices to attract investors. Manufacturing, pharmaceutical and oil-based industries flocked to Puerto Rico.

Beginning in the 1970s, however, these incentives decreased. As tax exemptions expired and wage standards rose, numerous companies left Puerto Rico. The net effect of Operation Bootstrap was to aggravate economic inequality and unemployment and contribute to the territory’s debt and environmental crises.

Currently the territory’s unemployment rate fluctuates between 10 and 12 percent. The legacies of rapid industrialization include polluted landscapes and heavy reliance on oil.

Puerto Rico generates almost all of its electricity from fossil fuels. About 50 percent comes from oil.

Puerto Ricans pay rates two to three times higher for electricity than continental U.S. residents. They also experience blackouts and other power disruptions caused by the grid’s aging infrastructure. A bankrupt public energy utility is largely responsible for these daily hardships.

Fast-forwarding energy projects

In 2011 Puerto Rican government officials began describing local energy challenges as an “energy emergency.” They used this framing to structure policy and sway public support for natural gas projects.

One example, the Vía Verde pipeline, was designed to deliver natural gas to northern Puerto Rico. Advocates claimed the project would reduce oil imports and lower electricity bills. Opponents of this widely unpopular proposal raised concerns about endangered species, heritage sites, human health, misleading financial benefits and the dismissal of renewable alternatives.

In 2012 the project was defeated by a broad-based coalition of local community members and Puerto Ricans in the U.S. diaspora. However, the Aguirre Offshore GasPort quickly emerged as an alternative. The GasPort would receive liquefied natural gas shipments from the United States and deliver the gas to shore via an underwater pipeline. Some nearby residents argue that the project will harm local fishers, wildlife and coral reefs. They also are worried about potential pipeline breaks and spills.

Excelerate Energy, the U.S.-based company planning to build the GasPort, connects speed, which it calls “energy fast forward”, with progress on its website to promote liquefied natural gas technology. However, the GasPort project ignores calls for local control of sustainable, renewable energy.

Earlier this month Excelerate withdrew its contract with Puerto Rico’s public energy utility because it is bankrupt. Excelerate claims it plans to move forward with required regulatory agencies to develop the project, and received support when the Puerto Rico Supreme Court ruled against a petition by grassroots group el Comité Diálogo Ambiental to invalidate the project’s environmental impact statement.

This accelerated approach is advanced by the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA, meaning “promise” in Spanish), enacted in 2016. The measure created a control board to impose austerity measures, and also authorizes fast-tracking of critical energy projects.

Critics, including energy experts and environmental justice activists, argue that while Puerto Rico certainly faces energy emergencies, the government is encouraging rushed project impact reviews that inhibit democratic engagement and renewable alternatives.

Energy expansionism

These controversies reflect struggles elsewhere against accelerated project development that denies self-determination. The Standing Rock Sioux and their allies confronted similar challenges when President Trump reversed President Obama’s decision to block the Dakota Access Pipeline. In June 2017 a federal court ruled the Trump administration had cut numerous corners in a review of the pipeline’s environmental impacts.

The fast-forward approach also is used by Fueling U.S. Forward, an organization funded by conservative billionaires Charles and David Koch. The group has targeted low-income communities and people of color, arguing that they are most impacted by energy price fluctuations and should have consistent access to fossil fuels. This strategy, which environmental justice advocates have described as “exploitative, sad and borderline racist,” obscures that these same communities are disproportionately burdened by pollution and environmental hazards, many linked to fossil fuel production and use.

Many Puerto Ricans oppose the continued use of their environment as a sacrifice zone for energy colonialism. For example, opposition to illegal coal ash dumping in the southern town of Peñuelas continues to intensify. Activists have used tactics including an encampment and a silent protest.

The University of Puerto Rico’s National Institute of Energy and Island Sustainability is working to foster democratic modes of engagement for developing a sustainable, renewable energy future. As a collaborator with local organizers, I have learned from residents who hope to achieve Puerto Rico’s first community-designed and -managed solar project in the town of Coquí.

These struggles for community control and climate and energy justice show that many Puerto Ricans reject continued reliance on fossil fuel to power their lives. In an encouraging sign, Puerto Rico’s electric utility has just announced plans to add 240 megawatts of large-scale solar generation by 2019.

Meanwhile, with the International Energy Agency predicting that the United States will become a top gas exporter, discussions of “energy dominance” and other related rhetoric will become increasingly relevant. These terms echo both past and present expansionist endeavors. The Trump administration’s policies are just the newest chapter.

Catalina M. de Onís collaborates with the Comité Diálogo Ambiental, a grassroots group in Salinas, Puerto Rico.

Read These Next

Green or not, US energy future depends on Native nations

Native American lands contain 30% of the nation’s coal, 50% of its uranium and 20% of its natural…

Philadelphia was once a sweet spot for chocolatiers and other candymakers who made iconic treats for

Goldenberg’s Peanut Chews, Goobers and Whitman’s Sampler boxes of chocolates are just a few confectionary…

How do scientists hunt for dark matter? A physicist explains why the mysterious substance is so hard

Dark matter doesn’t seem to interact with the matter we can see and touch, so scientists look for…