Hurricane Melissa turned sharply to devastate Jamaica − how forecasters knew where it was headed

Tropical storms are guided by many different wind patterns: big, like the Bermuda high, and small. A hurricane researcher explains their role in why so many storms veered off into the Atlantic in 2025.

Hurricane Melissa grew into one of the most powerful Atlantic tropical cyclones in recorded history on Oct. 28, 2025, hitting western Jamaica with 185 mph sustained winds. The Category 5 hurricane blew roofs off buildings and knocked down power lines, its torrential rainfall generated mudslides and flash flooding, and its storm surge inundated coastal areas.

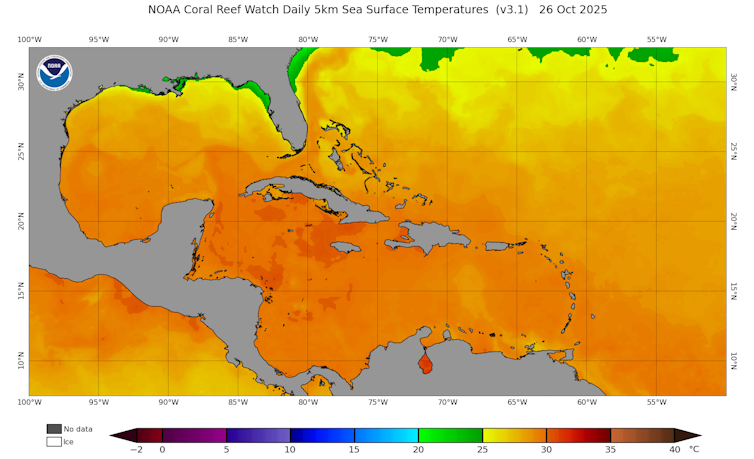

Melissa had been wobbling south of the island for days, quickly gaining strength over the hot Caribbean Sea, before taking a sharp turn to the northeast that morning.

As a hurricane researcher, I work with colleagues at NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory to improve predictions of hurricanes’ tracks and strengths. Accurate forecasts of Melissa’s turn to the northeast gave many people across Jamaica, Cuba and the eastern Bahamas extra time to evacuate to safer areas before the hurricane headed their way.

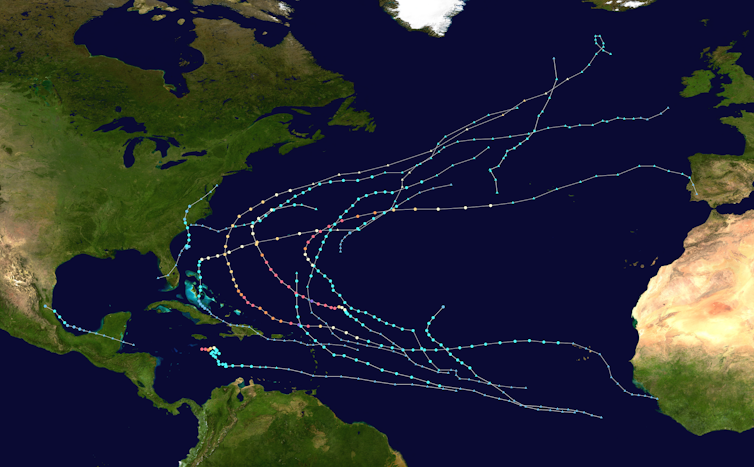

Throughout 2025, most hurricanes similarly veered off toward the open Atlantic, sparing the U.S. mainland. To understand the forces that shaped these storms and their paths, let’s take a closer look at Melissa and the 2025 hurricane season.

The origins of Atlantic tropical cyclones

Before they evolve into powerful hurricanes, storm systems start out as jumbled clusters of clouds over the open ocean.

Many of 2025’s Atlantic tropical cyclones began life far from the U.S. coastline in the warm waters west of Africa, near the Cape Verde islands. These Cape Verde hurricanes are consistently blown toward the United States, especially during peak hurricane season.

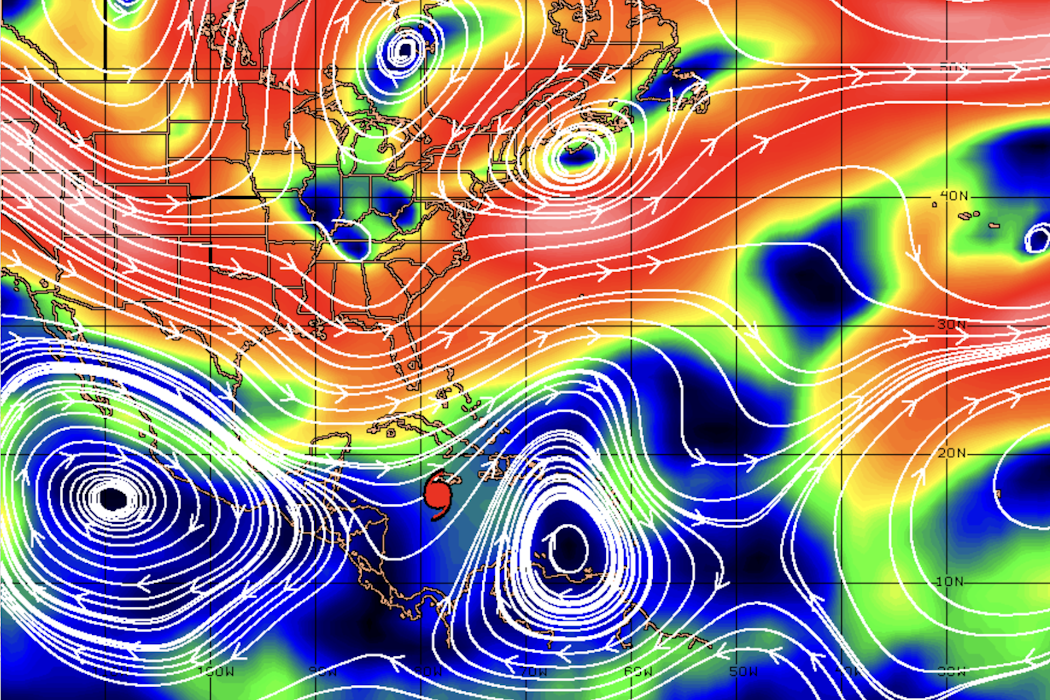

The driving force steering these storms is a hot, semi-permanent high-pressure air mass often found spinning above the Atlantic Ocean known as the Bermuda high or Azores high.

When this high-pressure system, or subtropical ridge, is positioned farther east, closer to the Azores islands, its strong, clockwise-rotating winds typically curve tropical cyclones briskly out to sea toward their demise in the cold North Atlantic. When the high-pressure ridge is closer to the U.S. and centered over Bermuda, it can send storms crashing into the U.S. coast.

Because that high-pressure system was positioned further east in summer and fall 2025, many of the season’s strongest storms, such as hurricanes Erin, Gabrielle and Humberto, swung east of the U.S. mainland. Combined with an active jet stream above the Southeast U.S., most tropical cyclones were steered away from the Atlantic coast.

The clouds that eventually became Hurricane Melissa traveled farther to the south, avoiding the Bermuda high and making their way into the Caribbean Sea.

Tropical cyclones’ high-stakes balancing act

After a tropical cyclone forms, its path is guided by the movement of air surrounding it, known as atmospheric steering currents. These steering currents direct the forward movement of storms in the Atlantic at speeds ranging from a sluggish 1 mph to a blistering 70 mph or more.

Hurricane Melissa’s meandering track was determined by these steering currents. At first, the system was caught between winds from high-pressure systems to its northwest and southeast. This setup trapped the storm over the warm Caribbean Sea for days, just to the south of Jamaica.

As a tropical cyclone is steered by outside forces, its internal makeup also constantly evolves, changing how the storm interacts with its steering currents.

When Hurricane Melissa was a weak, lopsided system, it didn’t receive much of a push from its upper-level environment. But as the hurricane gained strength from the very warm ocean below, it grew taller. Like a skyscraper reaching high into the air, major hurricanes like Melissa have towering thunderstorms and feel more of a push from upper-level winds than weaker storms do.

Melissa’s center also became aligned vertically, allowing the tropical cyclone to rapidly intensify from 70 mph to a staggering 140 mph sustained winds in 24 hours.

Eventually, the precarious atmospheric balancing act holding Melissa in place collapsed. A ripple in the jet stream known as an atmospheric trough steered the hurricane to the northeast and into the Jamaican coast.

Melissa’s snail’s pace of about 2 mph was rare but not unheard of. Slow storms like Melissa are more common in October, as steering currents are often very weak or pushing in opposite directions, which can trap a tropical cyclone in place. Similar steering currents affected Hurricane Matthew in 2016.

Tragically, stalled tropical cyclones often bring prolonged rainfall, winds, flash flooding and storm surge with them. The wind and downpours can be extreme for mountain communities, as their high topography enhances local rainfall that can trigger mudslides and flooding, as Jamaica saw from Melissa.

Improving storm track forecasting

Meteorologists generally understand how atmospheric steering currents guide tropical cyclones, yet forecasting these wind patterns remains a challenge. Depending on the atmospheric setup, certain hurricanes can be harder to forecast than others, as changes to steering currents can be subtle.

New approaches to hurricane track forecasting include using machine learning models, such as Google DeepMind, which outperformed many traditional models in forecasting storm tracks this hurricane season. Rather than solving a complex set of equations to make a forecast, DeepMind looks at statistics of previous hurricane tracks to infer the path of a current storm.

NOAA Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance data can also accelerate progress in predicting tropical cyclone paths. Recent tests show how accounting for specific measurements from within a hurricane can improve forecasts. Certain flight patterns that Hurricane Hunters and drones fly through strong hurricanes can also improve predictions of a storm’s path.

Scientists and engineers aim to further improve hurricane track and intensity forecasts through research into storm behavior and improving hurricane models to better inform the public when danger is on the way.

Ethan Murray receives funding from the Office of Naval Research and National Science Foundation. He works for The University of Miami and NOAA Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory.

Read These Next

Citizenship voting requirement in SAVE America Act has no basis in the Constitution – and ignores pr

The House has passed a bill to require proof of citizenship for voting. Although it likely won’t become…

Swarms of AI bots can sway people’s beliefs – threatening democracy

A simulation shows that social media bots powered by today’s AI can infiltrate human networks on social…

Martha Washington’s enslaved maid Ona Judge made a daring escape to freedom – but the National Park

Ona Judge was one of 9 people George Washington owned when he lived in the President’s House in Philadelphia.