How a corpse plant makes its terrible smell − it has a strategy, and its female flowers do most of t

When a corpse flower bloomed on campus, atmospheric scientists got to work. What they discovered provides new evidence about the unique pollination strategies of a very unusual flower.

Sometimes, doing research stinks. Quite literally.

Corpse plants are rare, and seeing one bloom is even rarer. They open once every seven to 10 years, and the blooms last just two nights. But those blooms – red, gorgeous and massive at over 10 feet (3 meters) tall – stink. Think rotting flesh or decaying fish.

Corpse plants definitely earn their nickname. Their pungent odors attract not only the carrion insects – beetles and flies normally drawn to decomposing meat – that pollinate the plants, but also crowds of onlookers curious about the rare, elaborate display and that putrid scent.

Plant biologists have studied corpse flowers for years, but as atmospheric chemists we were curious about something specific: the mixes of chemicals that create that smell and how they change during the flower’s short bloom.

While previous studies had identified dozens of volatile organic and sulfur compounds that contribute to corpse flower scents, no one had yet quantified those emission rates or looked at how the rates changed throughout a single evening. We recently got that opportunity. What we found opened a new window into the complexity and strategic behavior of a very unusual flower.

Meet Cosmo the corpse plant

Corpse plants are native to the Indonesian island of Sumatra but are considered endangered, even there. Several years ago, Colorado State University was given a corpse plant, or Titan arum (Amorphophallus titanum), to study. Its name is Cosmo – Titan arums are rare enough that they get names.

Cosmo sat dormant in the CSU plant growth facility for several years before showing signs that it was about to flower in spring 2024. When news came that Cosmo was going to bloom, we jumped at the opportunity to bring our atmospheric chemistry expertise into the greenhouse.

We deployed a series of devices for collecting air samples before, during and after the bloom. Then we measured chemicals in the air samples using a gas chromatography mass spectrometer, an instrument that is mentioned frequently on crime TV shows. Colleagues also brought a time-of-flight mass spectrometer that we placed downwind of Cosmo to measure volatile organic compounds every second.

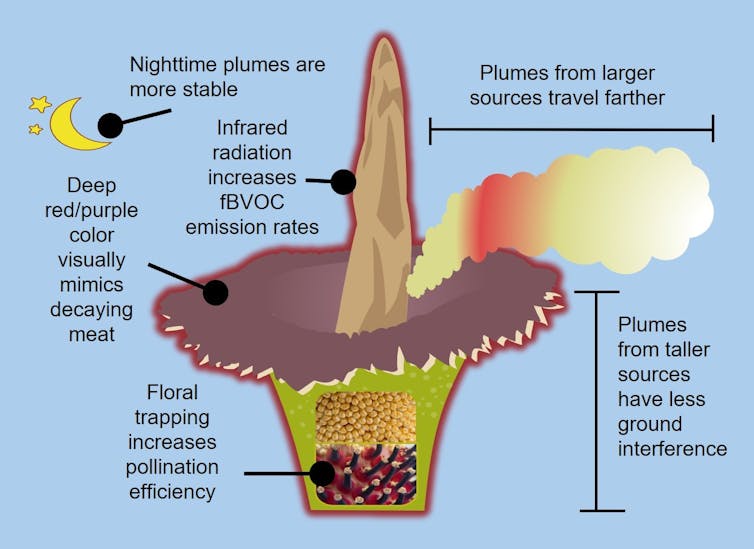

To make each rare bloom count, corpse plants put vast amounts of energy into the show, producing large flowers that can weigh more than 100 pounds. The plants heat themselves up using a biochemical process known as thermogenesis that enhances emissions of organic compounds that attract insects.

Corpse plant emissions are notorious. While some local communities revered the plants, others would try to destroy them. In the 19th century, European explorers actively collected Titan arum plants and distributed them throughout botanical gardens and conservatories around the world.

Corpse plants are dichogamous: Each has both male and female flowers. Inside the giant petal-like leaf called a spathe, each plant has a central spike called a spadix that is ringed with many rows of tiny female and male flowers near its base. These female and male flowers bloom at separate times to avoid self-pollination, and they are the source of the smell.

On the first night of a corpse plant bloom, the female flowers bloom to attract pollinators that, if they’re lucky, are carrying pollen from another corpse plant.

Then, on the second night, the male flowers bloom, allowing pollinating insects to carry pollen off to another corpse plant.

The rare blooms and avoidance of self-pollination highlight not only why these plants are listed as endangered but also their need for efficient pollination strategies – exactly the chemistry we wanted to investigate.

Female flowers work harder

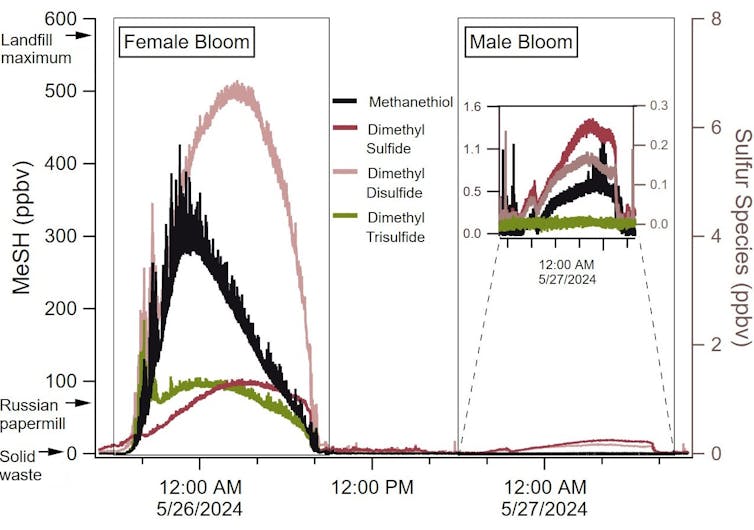

We found that the female flowers do most of the work attracting pollinators, as previous studies noted. They emit vast amounts of organic sulfur, plus some other compounds that mimic rotting smells to attract beetles and flies that normally feed on animal carcasses.

It’s this organic sulfur that really stinks from the female bloom: Methanethiol, a molecule in the same chemical family of compounds as the odors emitted by skunks, was the single most-emitted compound during Cosmo’s bloom.

We also measured many other organic sulfur compounds, including dimethyl disulfide, which has a garlic smell; dimethyl sulfide, known for an unpleasant scent; and dimethyl trisulfide, which smells like rotting cabbage or onions. We also measured dozens of other compounds: sweet-smelling benzyl alcohol, asphalt-scented phenol and fragrant benzaldehyde.

While previous studies found some of the same compounds with different instruments, we were able to measure the methanethiol and quantify the concentrations quickly enough to track the progress of the bloom overnight.

As Cosmo bloomed, we combined our instrument data with measurements of the air change rate in the greenhouse – meaning how fast it takes for air to move through the space – and were able to calculate the emission rates.

The volatile emissions added up to about 0.4% of the plant’s average biomass, meaning the plant, which we estimated to weigh about 100 pounds, lost a measurable amount of weight while producing those chemicals. That’s a lot of stench.

Floral trapping

The female flowers bloomed all night, but early the next morning the emissions rapidly stopped. We wondered whether this cutoff point just might be evidence of floral trapping: a pollination strategy employed by other members of Titan arum’s family.

During floral trapping, the floral chamber can physically close through movement of hairs or expansion of parts of the plant, such as the surrounding spathe. A physical closure of the floral chamber would not be easily visible to bystanders, but it could rapidly cut off the emissions the way we observed.

An Australian arum lily that smells like dung uses this technique. The carrion insects that come for the female flowers are forced to stay for the male flowers that bloom the next night, so they can carry off that pollen to find another female corpse bloom. Our evidence suggests that the corpse flower probably does too.

The second night, the emissions started back up – at much lower levels. The male flowers emit a sweeter set of aromatic compounds and far less sulfur than the females.

We hypothesize that the male flowers don’t need to work as hard to smell pungent in order to attract as many insects because insects are already there due to floral trapping. A 2023 study found that thermogenesis was also weaker during the male bloom: the spadix reached 96.8 degrees Fahrenheit (36 C) during the female bloom, but only 92 F (33.2 C) during the male bloom.

Stinkier than a landfill

We found that the corpse plant’s powerful emission rates can be an order of magnitude stronger than landfills – albeit only for two nights. These strong emissions are well designed to move far through the Sumatran jungle to attract carrion flies.

The odors are also resilient to atmospheric oxidation – the way organic compounds degrade in the atmosphere by reacting with oxidants in pollution such as ozone or nitrate radicals. Different compounds degrade at different rates – an important factor for attracting pollinators.

Many insects are attracted to not just one volatile compound, but by specific ratios of different volatile compounds. When atmospheric pollution degrades floral emissions and these ratios change, pollinators have a harder time finding flowers.

The female floral plume maintained a reasonably constant ratio of the major sulfur chemicals. The male plume, however, was far more susceptible to degrading in pollution and changing floral ratios in nighttime air.

These enigmatic plants put a lot of energy into clever pollination strategies. Cosmo taught us about their far-reaching scents of rotting meat, thermogenesis to increase emissions and floral entrapment, offering new insight into the corpse plant’s spectacular bloom.

Delphine Farmer receives funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the National Science Foundation, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of Energy, and the W.M. Keck Foundation.

Mj Riches receives funding from the National Science Foundation.

Rose Rossell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Massive US attacks on Iran unlikely to produce regime change in Tehran

President Trump has appealed to Iranians to topple their government, but a popular uprising is unlikely…

Iran will respond to US-Israeli strikes as existential threats to the regime – because they are

The latest attack on Iran goes far beyond previous operations by Israel and the US in both scale and…

Tiny recording backpacks reveal bats’ surprising hunting strategy

By listening in on their nightly hunts, scientists discovered that small, fringe-lipped bats are unexpectedly…