Solving the world’s microplastics problem: 4 solutions cities and states are trying after global tre

The world puts a lot of unnecessary microplastics into the environment − such as glitter in makeup. Even better filters in washing machines could help.

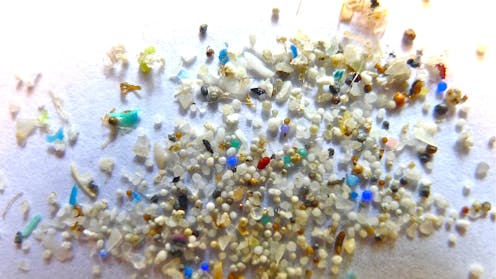

Microplastics seem to be everywhere – in the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat. They have turned up in human organs, blood, testicles, placentas and even brains.

While the full health consequences of that exposure are not yet known, researchers are exploring potential links between microplastics and negative health effects such as male infertility, inflammation, liver disease and other metabolic problems, and heart attack or stroke.

Countries have tried for the past few years to write a global plastics treaty that might reduce human exposure to plastic particles and their harm to wildlife and ecosystems, but the latest negotiations collapsed in August 2025. Most plastics are made with chemicals from fossil fuels, and oil-producing countries, including the U.S., have opposed efforts that might limit plastics production.

While U.S. and global solutions seem far off, policies to limit harm from microplastics are gaining traction at the state and local levels.

As an environmental lawyer and author of the book “Our Plastic Problem and How to Solve It,” I see four promising policy strategies.

Banning added microplastics: Glitter, confetti and turf

Some microplastics are deliberately manufactured to be small and added to products. Think glitter in cosmetics, confetti released at celebrations and plastic pellet infill, used between the blades in turf fields to provide cushion and stability.

These tiny plastics inevitably end up in the environment, making their way into the air, water and soil, where they can be inhaled or ingested by humans and other organisms.

California has proposed banning plastic glitter in personal care products. No other state has pursued glitter, however some cities, such as Boca Raton, Florida, have restricted plastic confetti. In 2023, the European Union passed a ban on all nonbiodegradable plastic glitter as well as microplastics intentionally added to products.

Artificial turf has also come under scrutiny. Although turf is popular for its low maintenance, these artificial fields shed microplastics.

European regulators targeted turf infill through the same law for glitter, and municipalities in Connecticut and Massachusetts are considering local bans.

Rhode Island’s proposed law, which would ban all intentionally added microplastics by 2029, is broad enough to include glitter, turf and confetti.

Reducing secondary microplastics: Textiles and tires

Most microplastics don’t start small; rather, they break off from larger items. Two of the biggest culprits of secondary microplastics are synthetic clothing and vehicle tires.

A study in 2019 estimated that textiles accounted for 35% of all microplastics entering the ocean – shed from polyester, nylon or acrylic clothing when washed. Microplastics can carry chemicals and other pollutants, which can bioaccumulate up the food chain.

In an effort to capture the fibers before they are released, France will require filters in all new washing machines by 2029.

Several U.S. states, including Oregon, Illinois, New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, are considering similar legislation. California came close in 2023, passing legislation to require microfiber filters for washing machines, but it was ultimately vetoed due to concerns about the cost of adding the filters. Even so, data submitted in support of the bill showed that such filters could cut microplastic releases from laundry by nearly 80%.

Some states, such as California and New York, are considering warnings on clothing made with synthetic fibers that would alert consumers to the shedding of microplastics.

Tires are another large source of microplastics. As they wear down, tires release millions of tons of particles annually, many of which end up in rivers and oceans. These particles include 6PPD-quinone, a chemical linked to mass die-offs of salmon in the Pacific Northwest.

One approach would be to redesign the product to include safer alternatives. California’s Department of Toxic Substances Control recently added 6PPD-quinone to its priority product list, requiring manufacturers to explain how they will either redesign their product or remove it from the market.

Regulating disposal

Microplastics can also be dealt with at the disposal stage.

Disposable wipes, for example, contain plastic fibers but are still flushed down toilets, clogging pipes and releasing microplastics. States such as New York, California and Michigan have passed “no-flush” labeling laws requiring clear warnings on packaging, alerting consumers to dispose of these wipes another way.

Construction sites also contribute to local microplastic pollution. Towns along the New Jersey shore have enacted ordinances that require builders to prevent microplastics from entering storm drains that can carry them to waterways and the ocean. Such methods include using saws and drills with vacuums to reduce the release of microplastics and cleaning worksites each day.

Oregon and Colorado have new producer responsibility laws that require manufacturers that sell products in plastic packaging to fund recycling programs. California requires manufacturers of expanded polystyrene plastic products to ensure increasing levels of recycling of their products.

Statewide strategies and disclosure laws

Some states are experimenting with broader, statewide strategies based on research.

California’s statewide microplastic strategy, eg: link error. adopted in 2022, is the first of its kind. It requires standardized testing for microplastics in drinking water and sets out a multiyear road map for reducing pollution from textiles, tires and other sources.

California has also begun treating microplastics themselves as a “chemical of concern.” That shifts disclosure and risk assessment obligations to manufacturers, rather than leaving the burden on consumers or local governments.

Other states are pursuing statewide strategies. Virginia, New Jersey and Illinois have considered bills to monitor microplastics in drinking water. A Minnesota bill would study microplastics in meat and poultry, and the findings and recommendations could influence future consumer safety regulations in the state.

State and local initiatives in the U.S. and abroad – be they bans, labels, disclosures or studies – can help keep microplastics out of our environment and lay the foundation for future large-scale regulation.

Federal ripple effects

These state-level initiatives are starting to influence policymakers in Washington.

In June 2025, the U.S. House passed the bipartisan WIPPES Act, modeled on state “no-flush” laws, and sent it to the Senate for consideration.

Another bipartisan bill was introduced in July 2025, the Microplastic Safety Act, which would direct the FDA to research microplastics’ human health impacts, particularly on children and reproductive systems.

Proposals to require microfiber filters in washing machines, first tested at the state level, are also being considered at the federal level.

This pattern is not new. A decade ago, state bans on wash-off cosmetic microbeads paved the way for the Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015, the only federal law to date that directly bans a type of microplastic. That history suggests today’s state and local actions could again catalyze broader national reform.

Small steps with big impact

Microplastics are a daunting challenge: They come from many sources, are hard to clean up once released, and pose risks to our health and the environment.

While global treaties and sweeping federal legislation remain out of reach, local and state governments are showing a path forward. These microsolutions may not eliminate microplastics, but they can reduce pollution in immediate and measurable ways, creating momentum for larger reforms.

Sarah J. Morath is affiliated with the Global Council for Science and the Environment.

Read These Next

Winter Olympians often compete in freezing temperatures – physiology and advances in materials scien

While physical exertion helps athletes stay warm, sweating can lead to dehydration.

Federal and state authorities are taking a 2-pronged approach to make it harder to get an abortion

Four years after the Supreme Court’s Dobbs ruling gave states the power to ban abortion, further restrictions…

US experiencing largest measles outbreak since 2000 – 5 essential reads on the risks, what to do and

Public health scholars worry that the resurgence of measles may signal a coming wave of other vaccine-preventable…