Wildfire season is starting weeks earlier in California – a new study shows how climate change is dr

Parts of California are seeing fire season start more than 10 weeks earlier now than in the 1990s.

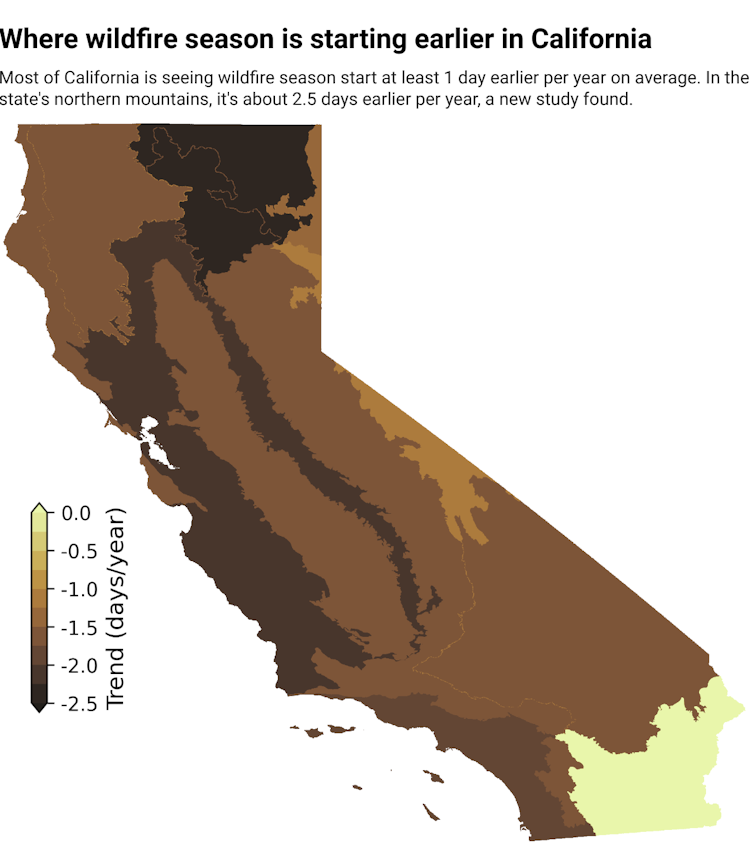

Fire season is expanding in California, with an earlier start to wildfire activity in most of the state. In parts of the northern mountains, the season is now starting more than 10 weeks earlier than it did in the 1990s, a new study shows.

Atmospheric scientists Gavin Madakumbura and Alex Hall, two authors of the study, explain how climate warming has been driving this trend and why the trend is likely to continue.

What did your study find about how wildfire season is changing?

Over the past three decades, California has seen a trend toward more destructive wildfire seasons, with more land burned, but also an earlier start to fire season. We wanted to find out how much of a role climate change was playing in that shift to an earlier start.

We looked at hundreds of thousands of fire records from 1992 to 2020 and documented when fire season started in each region of the state as temperatures rose and vegetation dried out.

While other research has observed changes in the timing of fire season in the western U.S., we identified the drivers of this trend and quantified their effects.

The typical onset of summer fire season, which is in May or June in many regions, has shifted earlier by at least one month in most of the state since the 1990s, and by about 2½ months in some regions, including the northern mountains. Of that, we found that human-caused climate change was responsible for advancing the season between six and 46 days earlier across most of the state from 1992 to 2020.

Our results suggest that as climate warming trends continue, this pattern will likely persist, with earlier starts to fire season in the coming years. This means longer fire seasons, increasing the potential for more of the state to burn.

California typically leads the nation in the number of wildfires, as well as the cost of wildfire damage. But the results also provide some insight into the risks ahead for other fire-prone parts of North America.

What’s driving the earlier start to fire season?

There are a few big contributors to long-term changes in wildfire activity. One is how much fuel is available to burn, such as grasses and trees. Another is the increase in ignition sources, including power lines, as more people move into wildland areas. A third is how dry the fuel is, or fuel aridity.

We found that fuel aridity, which is controlled by climate conditions, had the strongest influence on year-to-year shifts in the timing of the onset of fire season. The amount of potential fuel and increase in ignition sources, while contributing to fires overall, didn’t drive the trend in earlier fires.

Year-to-year, there will always be some natural fluctuations. Some years are wet, others dry. Some years are hotter than others. In our study, we separated the natural climate variations from changes driven by human-caused climate warming.

We found that increased temperatures and vapor pressure deficit – a measure of how dry the air is – are the primary ways climate warming is shifting the timing of the onset of fire season.

Just as a warmer, drier year can lead to an earlier fire season in a single year, gradual warming and drying caused by climate change are systematically advancing the start of fire seasons. This is happening because it is increasing fuel flammability.

Why has the start to fire season shifted more in some regions than others?

The biggest shifts we’ve seen in fire season timing in California have been in the northern mountains.

In the mountains, the winter snowpack typically keeps the ground and forests wet into summer, making it harder for fires to burn. But in warmer years, when the snowpack melts earlier, the fire potential rises earlier too.

Those warmer years are becoming more common. The reason climate change has a stronger impact in mountain regions is that snowpack is highly sensitive to warming. And when it melts sooner, vegetation dries out sooner.

In contrast, drier regions, such as desert ecoregions, are more sensitive to precipitation changes than to temperature changes. When assessing the influence of climate change in these areas, we mainly look at whether precipitation patterns have shifted due to climate warming. However, there is a lot of natural year-to-year variability in precipitation, and that makes it harder to identify the influence of climate change.

It’s possible that when precipitation changes driven by climate warming become strong enough, we may detect a stronger effect in these regions as well.

Gavin D. Madakumbura receives funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Alex Hall receives funding from the NSF, DOE, NOAA, LADWP, and State of California, among other sources.

Read These Next

AI’s growing appetite for power is putting Pennsylvania’s aging electricity grid to the test

As AI data centers are added to Pennsylvania’s existing infrastructure, they bring the promise of…

Why US third parties perform best in the Northeast

Many Americans are unhappy with the two major parties but seldom support alternatives. New England is…

Abortion laws show that public policy doesn’t always line up with public opinion

Polls indicate majority support for abortion rights in most states, but laws differ greatly between…