Why 2025 became the summer of flash flooding in America

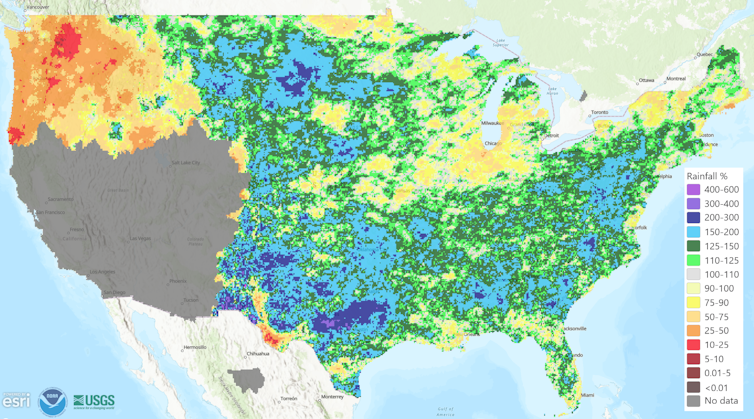

Large parts of the central and eastern U.S. have seen at least 50% more precipitation than normal. An atmospheric scientist explains why and what creates flash flood weather.

The National Weather Service has already issued more than 3,600 flash flood warnings across the United States in 2025, and that number is increasing as torrential downpours continue in late July. There’s a good chance the U.S. will exceed its yearly average of around 4,000 flash flood warnings soon.

For communities in Texas, New Mexico, West Virginia and New Jersey, the floods have been deadly. And many more states have seen flash flood damage in recent weeks, including New York, Oklahoma, Kansas, Vermont and Iowa.

What’s causing so much extreme rain and flooding?

I study extreme precipitation events along with the complex processes that lead to the devastating damage they cause.

Both the atmosphere and surface conditions play important roles in when and where flash floods occur and how destructive they become, and 2025 has seen some extremes, with large parts of the country east of the Rockies received at least 50% more precipitation than normal from mid-April through mid-July.

Excess water vapor, weaker jet stream

Flash floods are caused by excessive precipitation over short periods of time. When rain accumulates too fast for the local environment to absorb or reroute it, flooding ensues, and conditions can get dangerous fast.

During the warm season, intrusions of tropical air with excessive water vapor are common in the U.S., and they can result in intense downpours.

In addition, the jet stream and westerly winds – which move storm systems from west to east across the U.S. – tend to weaken during summer. As a result, the overall movement of thunderstorms and other precipitation-producing systems slows during the summer months, and storm systems can remain almost stationary over a location.

The combination of intense rainfall rates and extended precipitation increases the likelihood of flash flooding.

The surface rain falls on makes a difference, too

Local surface characteristics also play important roles in how flash floods develop and evolve.

When intense precipitation is combined with saturated soils, steep slopes, urban areas and sparse vegetation, runoff can quickly overwhelm local streams, rivers and drainage systems, leading to the rapid rise of water levels.

Because the characteristics of the surface can vary significantly along a stream or river, the timing and location of a heavy downpour pose unique risks for each local area.

What’s driving flash floods in 2025?

During the horrific flooding in Texas Hill Country on July 4, 2025, that killed more than 135 people, atmospheric water vapor in the region was at or near historic levels. The storm hit at the headwaters of the Guadalupe River, over streams that converge in the river valley.

As thunderstorms developed and remained nearly stationary over the region, they were fueled by the excessive atmospheric water vapor. That led to high rainfall rates. Hours of heavy rainfall early that morning sent the river rising quickly at a summer camp near Hunt, Texas, where more than two dozen girls and staff members died. Downstream at Kerrville, the river rose even faster, gaining more than 30 feet in 45 minutes.

Overall, a persistent atmospheric pattern in late spring and summer 2025 has included a shift of the jet stream farther to the south than normal and, along with lower atmospheric pressures, has supported excessive rainfall across the central and eastern U.S.

While the West Coast has experienced dry conditions in early summer 2025 due to a ridge of high pressure, the U.S. east of the Rockies has seen an active storm track with frontal boundaries and disturbances that produced thunderstorms and intense downpours across the region.

Warmer-than-normal ocean water can also boost rainfall. The Caribbean and the Atlantic Ocean are source regions for atmospheric water vapor in the central and eastern U.S. In summer 2025, that water vapor has created extremely humid conditions, which have produced very high rainfall rates when storms develop.

The result has been flash floods in several states producing catastrophic destruction and loss of life.

Looking to the future

The U.S. has seen devastating flash floods throughout its history, but rising global temperatures today are increasing the risk of flooding.

As ocean and air temperatures rise, atmospheric water vapor increases. Higher ocean temperatures can produce more atmospheric water vapor through evaporation, and a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, fueling downpours. In some high-risk areas, meteorologists, aware of the risks, say they are becoming more proactive about warnings.

Currently, evidence shows that atmospheric water vapor is increasing in the overall global climate system as temperatures rise.

Jeffrey Basara receives funding from the National Science Foundation, NASA, and NOAA.

Read These Next

Persian Gulf desalination plants could become military targets in regional war

Key sources of drinking water have been targets in past conflicts. And Iranian strikes have already…

Billions of dollars, decades of progress spent eliminating devastating diseases may be lost with und

Public health campaigns had made significant strides toward eradicating diseases like elephantitis and…

How Denver’s Northeast Park Hill community reduced youth violence by 75%

A neighborhood coalition identified risk factors for youth violence and prevention strategies.