Extreme weather’s true damage cost is often a mystery – that’s a problem for understanding storm ris

Forecasters already patch together very rough estimates, and ending NOAA’s ‘billion-dollar disasters’ list means less access to insurance data. Texas’ state climatologists explain why that matters.

On Jan. 5, 2025, at about 2:35 in the afternoon, the first severe hailstorm of the season dropped quarter-size hail in Chatham, Mississippi. According to the federal storm events database, there were no injuries, but it caused $10,000 in property damage.

How do we know the storm caused $10,000 in damage? We don’t.

That estimate is probably a best guess from someone whose primary job is weather forecasting. Yet these guesses, and thousands like them, form the foundation for publicly available tallies of the costs of severe weather.

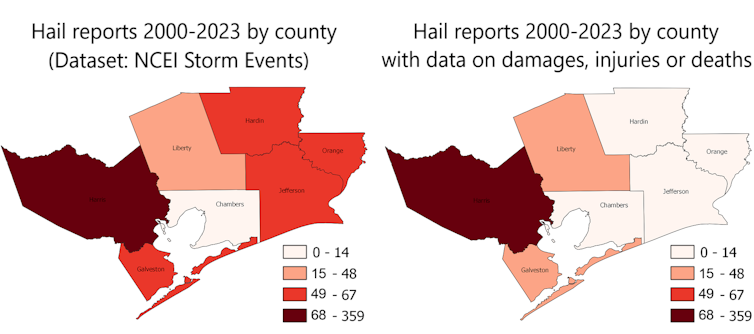

If the damage estimates from hailstorms are consistently lower in one county than the next, potential property buyers might think it’s because there’s less risk of hailstorms. Instead, it might just be because different people are making the estimates.

We are atmospheric scientists at Texas A&M University who lead the Office of the Texas State Climatologist. Through our involvement in state-level planning for weather-related disasters, we have seen county-scale patterns of storm damage over the past 20 years that just didn’t make sense. So, we decided to dig deeper.

We looked at storm event reports for a mix of seven urban and rural counties in southeast Texas, with populations ranging from 50,000 to 5 million. We included all reported types of extreme weather. We also talked with people from the two National Weather Service offices that cover the area.

Storm damage investigations vary widely

Typically, two specific types of extreme weather receive special attention.

After a tornado, the National Weather Service conducts an on-site damage survey, examining its track and destruction. That survey forms the basis for the official estimate of a tornado’s strength on the enhanced Fujita scale. Weather Service staff are able to make decent damage cost estimates from knowledge of home values in the area.

They also investigate flash flood damage in detail, and loss information is available from the National Flood Insurance Program, the main source of flood insurance for U.S. homes.

Most other losses from extreme weather are privately insured, if they’re insured at all.

Insured loss information is collected by reinsurance companies – the companies that insure the insurance companies – and gets tabulated for major events. Insurance companies use their own detailed information to try to make better decisions on rates than their competitors do, so event-based loss data by county from insurance companies isn’t readily available.

Losing billion-dollar disaster data

There’s one big window into how disaster damage has changed over the years in the U.S.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, compiled information for major disasters, including insured losses by state. Bulk data won’t tell communities or counties about their specific risk, but it enabled NOAA to calculate overall damage estimates, which it released as its billion-dollar disasters list.

From that program, we know that the number and cost of billion-dollar disasters in the United States has increased dramatically in recent years. News articles and even scientific papers often point to climate change as the primary culprit, but a much larger driver has been the increasing number and value of buildings and other types of infrastructure, particularly along hurricane-prone coasts.

Critics in the past year called for more transparency and vetting of the procedures used to estimate billion-dollar disasters. But that’s not going to happen, because NOAA in May 2025 stopped making billion-dollar disaster estimates and retired its user interface.

Previous estimates can still be retrieved from NOAA’s online data archive, but by shutting down that program, the window into current and future disaster losses and insurance claims is now closed.

Emergency managers at the county level also make local damage estimates, but the resources they have available vary widely. They may estimate damages only when the total might be large enough to trigger a disaster declaration that makes relief funds available from the federal government.

Patching together very rough estimates

Without insurance data or county estimates, the local offices of the National Weather Service are on their own to estimate losses.

There is no standard operating procedure that every office must follow. One office might choose to simply not provide damage estimates for any hailstorms because the staff doesn’t see how it could come up with accurate values. Others may make estimates, but with varying methods.

The result is a patchwork of damage estimates. Accurate values are more likely for rare events that cause extensive damage. Loss estimates from more frequent events that don’t reach a high damage threshold are generally far less reliable.

Do you want to look at local damage trends? Forget about it. For most extreme weather events, estimation methods vary over time and are not documented.

Do you want to direct funding to help communities improve resilience to natural disasters where the need is greatest? Forget about it. The places experiencing the largest per capita damages depend not just on actual damages but on the different practices of local National Weather Service offices.

Are you moving to a location that might be vulnerable to extreme weather? Companies are starting to provide localized risk estimates through real estate websites, but the algorithms tend to be proprietary, and there’s no independent validation.

4 steps to improve disaster data

We believe a few fixes could make NOAA’s storm events database and the corresponding values in the larger SHELDUS database, managed by Arizona State University, more reliable. Both databases include county-level disasters and loss estimates for some of those disasters.

First, the National Weather Service could develop standard procedures for local offices for estimating disaster damages.

Second, additional state support could encourage local emergency managers to make concrete damage estimates from individual events and share them with the National Weather Service. The local emergency manager generally knows the extent of damage much better than a forecaster sitting in an office a few counties away.

Third, state or federal governments and insurance companies can agree to make public the aggregate loss information at the county level or other scale that doesn’t jeopardize the privacy of their policyholders. If all companies provide this data, there is no competitive disadvantage for doing so.

Fourth, NOAA could create a small “tiger team” of damage specialists to make well-informed, consistent damage estimates of larger events and train local offices on how to handle the smaller stuff.

With these processes in place, the U.S. wouldn’t need a billion-dollar disasters program anymore. We’d have reliable information on all the disasters.

John Nielsen-Gammon receives funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the State of Texas.

William Baule receives funding from NOAA, the State of Texas, & the Austin Community Foundation.

Read These Next

Taboo tics like shouting curses and slurs are uncommon in Tourette syndrome − but people who have th

Obscene language tics, called coprolalia, don’t reveal what people with Tourette’s think and feel.…

Why does pain last longer for women? Immune cells may be the culprit

Your immune systems kicks into gear when you’re injured, both worsening and relieving pain.

Why ICE’s body camera policies make the videos unlikely to improve accountability and transparency

For body cameras to function as transparency tools, wrongdoing would have to be consistently penalized,…