California plan to ban most plants within 5 feet of homes for wildfire safety overlooks some importa

Hedges and trees may actually reduce home exposure to radiant heat and flying embers, but they must be well maintained. Two scientists who study how plants burn explain.

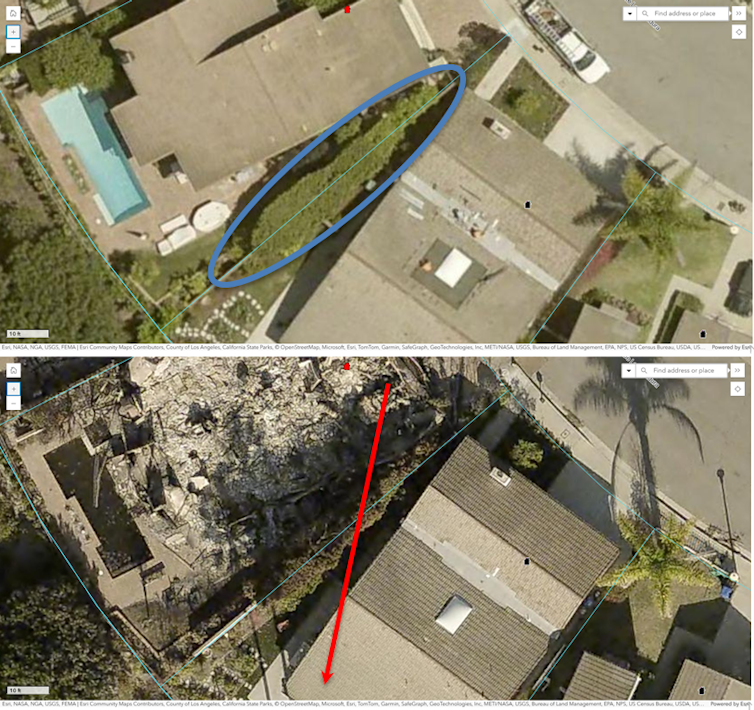

One of the most striking patterns in the aftermath of many urban fires is how much unburned green vegetation remains amid the wreckage of burned neighborhoods.

In some cases, a row of shrubs may be all that separates a surviving house from one that burned just a few feet away.

As scientists who study how vegetation ignites and burns, we recognize that well-maintained plants and trees can actually help protect homes from wind-blown embers and slow the spread of fire in some cases. So, we are concerned about new wildfire protection regulations being developed by the state of California that would prohibit almost all plants and other combustible material within 5 feet of homes, an area known as “Zone 0.”

Wildfire safety guidelines have long encouraged homeowners to avoid having flammable materials next to their homes. But the state’s plan for an “ember-resistant zone,” being expedited under an executive order from Gov. Gavin Newsom, goes further by also prohibiting grass, shrubs and many trees in that area.

If that prohibition remains in the final regulation, it’s likely to be met with public resistance. Getting these rules right also matters beyond California, because regulations that originate in California often ripple outward to other fire-prone regions.

Lessons from the devastation

Research into how vegetation can reduce fire risk is a relatively new area of study. However, the findings from plant flammability studies and examination of patterns of where vegetation and homes survive large urban fires highlight its importance.

When surviving plants do appear scorched after these fires, it is often on the side of the plant facing a nearby structure that burned. That suggests that wind-blown embers ignited houses first: The houses were then the fuel as the fire spread through the neighborhood.

We saw this repeatedly in the Los Angeles area after wildfires destroyed thousands of homes in January 2025. The pattern suggests a need to focus on the many factors that can influence home losses.

Several guides are available that explain steps homeowners can take to help protect houses, particularly from wind-blown embers, known as home hardening.

For example, installing rain gutter covers to keep dead leaves from accumulating, avoiding flammable siding and ensuring that vents have screens to prevent embers from getting into the attic or crawl space can lower the risk of the home catching fire.

However, guidance related to landscaping plants varies greatly and can even be incorrect.

For example, some “fire-safe” plant lists contain species that are drought tolerant but not necessarily fire resistant. What matters more for keeping plants from becoming fuel for fires is how well they’re maintained and whether they’re properly watered.

How a plant bursts into flames

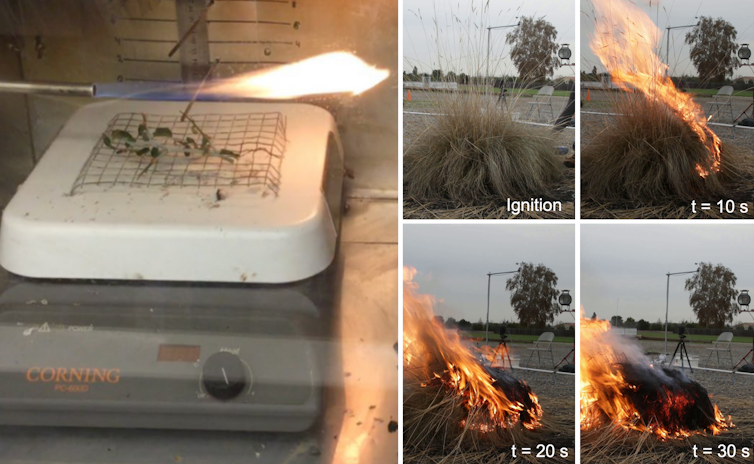

When living plant material is heated by a nearby energy source, such as a fire, the moisture inside it must be driven off before it can ignite. That evaporation cools the surrounding area and lowers the plant’s flammability.

In many cases, high moisture can actually keep a plant from igniting. We’ve seen this in some of our experimental work and in other studies that test the flammability of ornamental landscaping.

With enough heat, dried leaves and stems can break down and volatilize into gases. And, at that point, a nearby spark or flame can ignite these gases and set the plant on fire.

Even when the plant does burn, however, its moisture content can limit other aspects of flammability, such as how hot it burns.

Up to the point that they actually burn, green, well-maintained plants can slow the spread of a fire by serving as “heat sinks,” absorbing energy and even blocking embers. This apparent protective role has been observed in both Australia and California studies of home losses.

How often vegetation buffers homes from igniting during urban conflagrations is still unclear, but this capability has implications for regulations.

California’s ‘Zone 0’ regulations

The Zone 0 regulations California’s State Board of Forestry is developing are part of broader efforts to reduce fire risk around homes and communities. They would apply in regions considered at high risk of wildfires or defended by CAL FIRE, the state’s firefighting agency.

Many of the latest Zone 0 recommendations, such as prohibiting mulch and attached fences made of materials that can burn, stem from large-scale tests conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety. These features can be systematically analyzed.

But vegetation is far harder to model. The state’s proposed Zone 0 regulations oversimplify complex conditions in real neighborhoods and go beyond what is currently known from scientific research regarding plant flammability.

A mature, well-pruned shrub or tree with a high crown may pose little risk of burning and can even reduce exposure to fires by blocking wind and heat and intercepting embers. Aspen trees, for example, have been recommended to reduce fire risk near structures or other high-value assets.

In contrast, dry, unmanaged plants under windows or near fences may ignite rapidly and make it more likely that the house itself will catch fire.

As California and other states develop new wildfire regulations, they need to recognize the protective role that well-managed plants can play, along with many other benefits of urban vegetation.

We believe the California proposal’s current emphasis on highly prescriptive vegetation removal, instead of on maintenance, is overly simplistic. Without complementary requirements for hardening the homes themselves, widespread clearing of landscaping immediately around homes could do little to reduce risk and have unintended consequences.

Max Moritz has nothing to disclose.

Luca Carmignani has nothing to disclose.

Read These Next

Failure of US-Iran talks was all-too predictable – but Trump could still have stuck with diplomacy o

Silence from the US side after a third round of indirect talks and frustration expressed by President…

Kansas revoked transgender people’s IDs overnight – researchers anticipate cascading health and soci

With invalid driver’s licenses and birth certificates, transgender people are at risk for more than…

Nanoparticles and artificial intelligence can help researchers detect pollutants in water, soil and

Tiny particles bounce light around in a unique way, a property that researchers are using to detect…