NOAA’s 2025 hurricane forecast warns of a busy season – a storm scientist explains why and what mete

The preseason forecast is just the 30,000-foot view of what’s likely. Here’s what forecasters will be watching for over the weeks and months ahead.

U.S. forecasters are expecting an above-normal 2025 Atlantic hurricane season, with 13 to 19 named storms, and 6 to 10 of those becoming hurricanes.

Every year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and other forecasters release preseason outlooks for the Atlantic’s hurricane season, which runs June 1 through November 30.

So, how do they know what’s likely to happen months in the future?

I’m an atmospheric scientist who studies extreme weather. Let’s take a look at what Atlantic hurricane forecasts are based on and why those forecasts can shift during the season.

What goes into a seasonal forecast

Think of the preseason hurricane forecast as the 30,000-foot view: It can’t predict if or when a storm will hit a particular location, but it can offer insight into how many storms are likely to form throughout the entire Atlantic, and how active the season overall might be.

These outlooks rely heavily on two large-scale climate factors.

The first is the sea surface temperature in areas where tropical cyclones tend to form and grow. Hurricanes draw their energy from warm ocean water. So when the Atlantic is unusually warm, as it has been in recent years, it provides more fuel for storms to form and intensify.

The second key ingredient that meteorologists have their eye on is the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, which forecasters refer to as ENSO. ENSO is a climate cycle that shifts every few years between three main phases: El Niño, La Niña, and a neutral space that lives somewhere in between.

During El Niño, winds over the Atlantic high up in the troposphere – roughly 25,000 to 40,000 feet – strengthen and can disrupt storms and hurricanes. La Niña, on the other hand, tends to reduce these winds, making it easier for storms to form and grow. When you look over the historical hurricane record, La Niña years have tended to be busier than their El Niño counterparts, as we saw from 2020 through 2023.

We’re in the neutral phase as the 2025 hurricane season begins, and probably will be for at least a few more months. That means upper-level winds aren’t particularly hostile to hurricanes, but they’re not exactly rolling out the red carpet either.

At the same time, sea surface temperatures are running warmer than the 30-year average, but not quite at the record-breaking levels seen in some recent seasons.

Taken together, these conditions point to a moderately above-average hurricane season.

It’s important to emphasize that these factors merely load the dice, tilting the odds toward more or fewer storms, but not guaranteeing an outcome. A host of other variables influence whether a storm actually forms, how strong it becomes, and whether it ever threatens land.

The smaller influences forecasters can’t see yet

Once hurricane season is underway, forecasters start paying close attention to shorter-term influences.

These subseasonal factors evolve quickly enough that they don’t shape the entire season. However, they can noticeably raise or lower the chances for storms developing in the coming two to four weeks.

One factor is dust lofted from the Sahara Desert by strong winds and carried from east to west across the Atlantic.

These dust plumes tend to suppress hurricanes by drying out the atmosphere and reducing sunlight that reaches the ocean surface. Dust outbreaks are next-to-impossible to predict months in advance, but satellite observations of growing plumes can give forecasters a heads-up a couple weeks before the dust reaches the primary hurricane development region off the coast of Africa.

Another key ingredient that doesn’t go into seasonal forecasts but becomes important during the season are African easterly waves. These “waves” are clusters of thunderstorms that roll off the West African coast, tracking from east to west across the ocean. Most major storms in the Atlantic basin, especially in the peak months of August and September, can trace their origins back to one of these waves.

Forecasters monitor strong waves as they begin their westward journey across the Atlantic, knowing they can provide some insight about potential risks to U.S. interests one to two weeks in advance.

Also in this subseasonal mix is the Madden–Julian Oscillation. The MJO is a wave-like pulse of atmospheric activity that moves slowly around the tropics every 30 to 60 days. When the MJO is active over the Atlantic, it enhances the formation of thunderstorms associated with hurricanes. In its suppressed phase, storm activity tends to die down. The MJO doesn’t guarantee storms – or a lack of them – but it turns up or down the odds. Its phase and position can be tracked two or three weeks in advance.

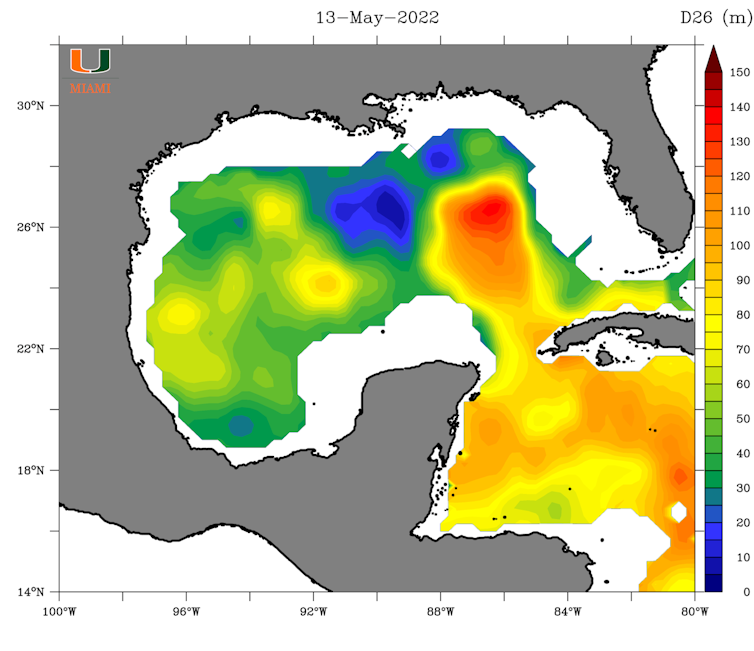

Lastly, forecasters will talk about the Loop Current, a deep river of warm water that flows from the Caribbean into the Gulf of Mexico.

When storms pass over the Loop Current or its warm eddies, they can rapidly intensify because they are drawing energy from not just the warm surface water but from warm water that’s tens of meters deep. The Loop Current has helped power several historic Gulf storms, including Hurricanes Katrina in 2005 and Ida in 2021.

But the Loop Current is always shifting. Its strength and location in early summer may look very different by late August or September.

Combined, these subseasonal signals help forecasters fine-tune their outlooks as the season unfolds.

Where hurricanes form shifts over the months

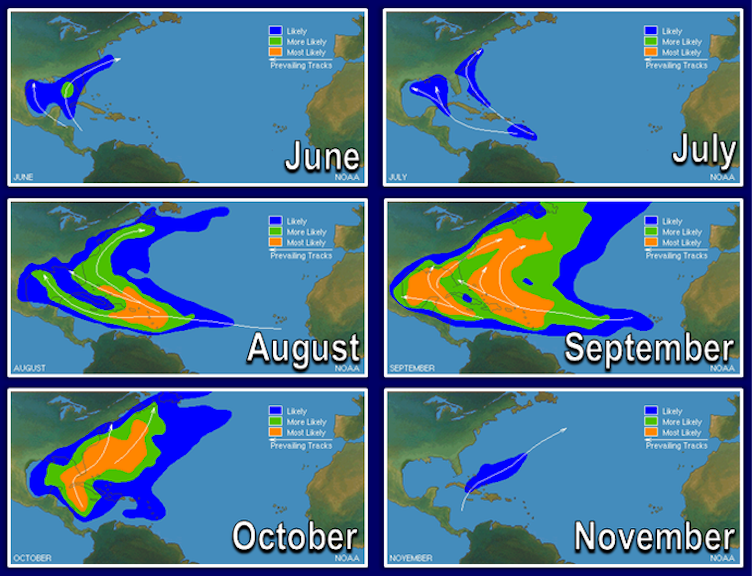

Where storms are most likely to form and make landfall also changes as the pages of the calendar turn.

In early summer, the Gulf of Mexico warms up faster than the open Atlantic, making it a notable hotspot for early-season tropical storm development, especially in June and July. The Texas coast, Louisiana, and the Florida Panhandle often face a higher early-season risk than locations along the Eastern seaboard.

By August and September, the season reaches its peak. This is when those waves moving off the coast of Africa become a primary source of storm activity. These long-track storms are sometimes called “Cape Verde hurricanes” because they originate near the Cape Verde Islands off the African coast. While many stay over open water, others can gather steam and track toward the Caribbean, Florida or the Carolinas.

Later in the hurricane season, storms are more likely to form in the western Atlantic or Caribbean, where waters are still warm and upper-level winds remain favorable. These late-season systems have a higher probability of following atypical paths, as Sandy did in 2012 when it struck the New York City region and Milton did in 2024 before making landfall in Florida.

At the end of the day, the safest way to think about hurricane season is this: If you live along the coast, don’t let your guard down. Areas susceptible to hurricanes are never totally immune from hurricanes, and it only takes one to make it a dangerous – and unforgettable – season.

Colin Zarzycki's research lab receives funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation, Department of Energy, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Read These Next

Failure of US-Iran talks was all-too predictable – but Trump could still have stuck with diplomacy o

Silence from the US side after a third round of indirect talks and frustration expressed by President…

Kansas revoked transgender people’s IDs overnight – researchers anticipate cascading health and soci

With invalid driver’s licenses and birth certificates, transgender people are at risk for more than…

Massive US attacks on Iran unlikely to produce regime change in Tehran

President Trump has appealed to Iranians to topple their government, but a popular uprising is unlikely…