Why protecting wildland is crucial to American freedom and identity

Thanks to the power of writer Wallace Stegner, Americans have for decades been able to put words to the importance wilderness holds in the nation’s history and imagination.

As summer approaches, millions of Americans begin planning or taking trips to state and national parks, seeking to explore the wide range of outdoor recreational opportunities across the nation. A lot of them will head toward the nation’s wilderness areas – 110 million acres, mostly in the West, that are protected by the strictest federal conservation rules.

When Congress passed the Wilderness Act in 1964, it described wilderness areas as places that evoked mystery and wonder, “where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” These are wild landscapes that present nature in its rawest form.

The law requires the federal government to protect these areas “for the permanent good of the whole people.” Wilderness areas are found in national parks, conservation land overseen by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, national forests and U.S. Fish and Wildlife refuges.

In early May 2025, the U.S. House of Representatives began to consider allowing the sale of federal lands in six counties in Nevada and Utah, five of which contain wilderness areas. Ostensibly, these sales are to promote affordable housing, but the reality is that the proposal, introduced by U.S. Rep. Mark Amodei, a Nevada Republican, is a departure from the standard process of federal land exchanges that accommodate development in some places but protect wilderness in others.

Regardless of whether Americans visit their public lands or know when they have crossed a wilderness boundary, as environmental historians we believe that everyone still benefits from the existence and protection of these precious places.

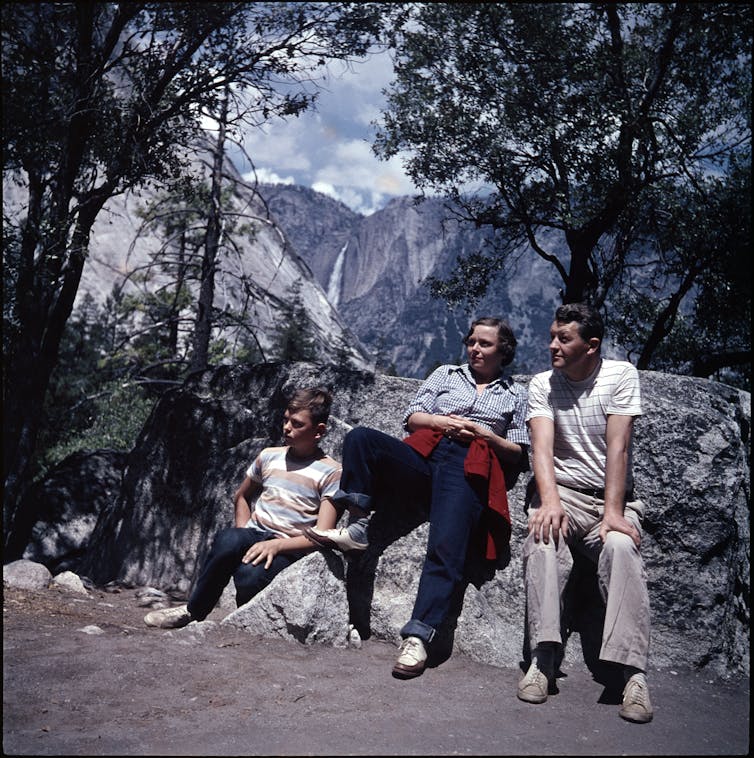

This belief is an idea eloquently articulated and popularized 65 years ago by the noted Western writer Wallace Stegner. His eloquence helped launch the modern environmental movement and gave power to the idea that the nation’s public lands are a fundamental part of the United States’ national identity and a cornerstone of American freedom.

Humble origins

In 1958, Congress established the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission to examine outdoor recreation in the U.S. in order to determine not only what Americans wanted from the outdoors, but to consider how those needs and desires might change decades into the future.

One of the commission’s members was David E. Pesonen, who worked at the Wildland Research Center at the University of California at Berkeley. He was asked to examine wilderness and its relationship to outdoor recreation. Pesonen later became a notable environmental lawyer and leader of the Sierra Club. But at the time, Pesonen had no idea what to say about wilderness.

However, he knew someone who did. Pesonen had been impressed by the wild landscapes of the American West in Stegner’s 1954 history “Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West.” So he wrote to Stegner, who at the time was at Stanford University, asking for help in articulating the wilderness idea.

Stegner’s response, which he said later was written in a single afternoon, was an off-the-cuff riff on why he cared about preserving wildlands. This letter became known as the Wilderness Letter and marked a turning point in American political and conservation history.

Pesonen shared the letter with the rest of the commission, which also shared it with newly installed Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall. Udall found its prose to be so profound, he read it at the seventh Wilderness Conference in 1961 in San Francisco, a speech broadcast by KCBS, the local FM radio station. The Sierra Club published the letter in the record of the conference’s proceedings later that year.

But it was not until its publication in The Washington Post on June 17, 1962, that the letter reached a national audience and captured the imagination of generations of Americans.

An eloquent appeal

In the letter, Stegner connected the idea of wilderness to a fundamental part of American identity. He called wilderness “something that has helped form our character and that has certainly shaped our history as a people … the challenge against which our character as a people was formed … (and) the thing that has helped to make an American different from and, until we forget it in the roar of our industrial cities, more fortunate than other men.”

Without wild places, he argued, the U.S. would be just like every other overindustrialized place in the world.

In the letter, Stegner expressed little concern with how wilderness might support outdoor recreation on public lands. He didn’t care whether wilderness areas had once featured roads, trails, homesteads or even natural resource extraction. What he cared about was Americans’ freedom to protect and enjoy these places. Stegner recognized that the freedom to protect, to restrain ourselves from consuming, was just as important as the freedom to consume.

Perhaps most importantly, he wrote, wilderness was “an intangible and spiritual resource,” a place that gave the nation “our hope and our excitement,” landscapes that were “good for our spiritual health even if we never once in ten years set foot in it.”

Without it, Stegner lamented, “never again will Americans be free in their own country from the noise, the exhausts, the stinks of human and automotive waste.” To him, the nation’s natural cathedrals and the vaulted ceiling of the pure blue sky are Americans’ sacred spaces as much as the structures in which they worship on the weekends.

Stegner penned the letter during a national debate about the value of preserving wild places in the face of future development. “Something will have gone out of us as a people,” he wrote, “if we ever let the remaining wilderness be destroyed.” If not protected, Stegner believed these wildlands that had helped shape American identity would fall to what he viewed as the same exploitative forces of unrestrained capitalism that had industrialized the nation for the past century. Every generation since has an obligation to protect these wild places.

Stegner’s Wilderness Letter became a rallying cry to pass the Wilderness Act. The closing sentences of the letter are Stegner’s best: “We simply need that wild country available to us, even if we never do more than drive to its edge and look in. For it can be a means of reassuring ourselves of our sanity as creatures, a part of the geography of hope.”

This phrase, “the geography of hope,” is Stegner’s most famous line. It has become shorthand for what wilderness means: the wildlands that defined American character on the Western frontier, the wild spaces that Americans have had the freedom to protect, and the natural places that give Americans hope for the future of this planet.

America’s ‘best idea’

Stegner returned to themes outlined in the Wilderness Letter again two decades later in his essay “The Best Idea We Ever Had: An Overview,” published in Wilderness magazine in spring 1983.

Writing in response to the Reagan administration’s efforts to reduce protection of the National Park System, Stegner declared that the parks were “Absolutely American, absolutely democratic.” He said they reflect us as a nation, at our best rather than our worst, and without them, millions of Americans’ lives, his included, would have been poorer.

Public lands are more than just wilderness or national parks. They are places for work and play. They provide natural resources, wildlife habitat, clean air, clean water and recreational opportunities to small towns and sprawling metro areas alike. They are, as Stegner said, cures for cynicism and places of shared hope.

Stegner’s words still resonate as Americans head for their public lands and enjoy the beauty of the wild places protected by wilderness legislation this summer. With visitor numbers increasing annually and agency budgets at historic lows, we believe it is useful to remember how precious these places are for all Americans. And we agree with Stegner that wilderness, public lands writ large, are more valuable to Americans’ collective identity and expression of freedom than they are as real estate that can be sold or commodities that can be extracted.

Leisl Carr Childers has received funding from the USDA Forest Service, the Henry Luce Foundation, Colorado Parks and Wildlife, and Charles Redd Center for Western Studies.

Michael Childers has received funding from the USDA Forest Service, the Henry Luce Foundation, Colorado Parks and Wildlife, and the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies.

Read These Next

Held captive in their own country during World War II, Japanese Americans used nature to cope with t

Incarcerated in rough barracks surrounded by barbed wire and armed soldiers, Japanese Americans made…

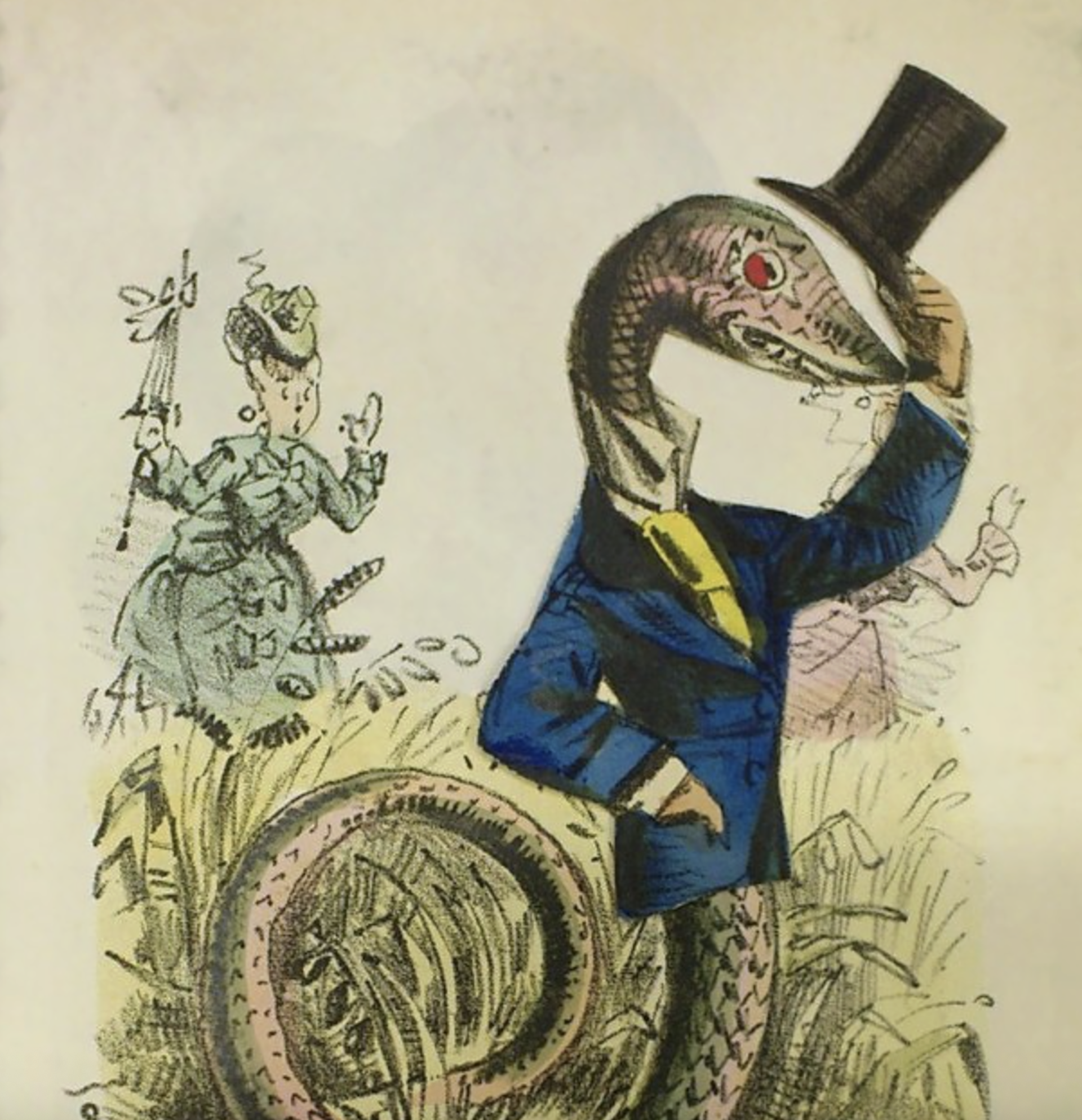

Valentine’s Day cards too sugary sweet for you? Return to the 19th-century custom of the spicy ‘vine

Victorians found a way to anonymously tell people they didn’t like exactly how they felt.

Philadelphia was once a sweet spot for chocolatiers and other candymakers who made iconic treats for

Goldenberg’s Peanut Chews, Goobers and Whitman’s Sampler boxes of chocolates are just a few confectionary…