Supreme Court sides with San Francisco, requiring EPA to set specific targets in water pollution per

San Francisco argued that Clean Water Act permits should function like recipes that restrict specific ingredients in a dish, rather than telling cooks not to make the dish too salty.

The U.S. Supreme Court has limited how flexible the Environmental Protection Agency and states can be in regulating water pollution under the Clean Water Act in a ruling issued March 4, 2025. However, the justices kept the decision relatively narrow.

The ruling only prohibits federal and state permitting agencies from issuing permits that are effectively broad orders not to violate water quality standards. In this case, the city and county of San Francisco argued successfully that the EPA’s requirements were not clear enough.

My research focuses on water issues, including the Clean Water Act and the Supreme Court’s interpretations of it. In my view, regulators still will have multiple options for limiting the pollutants that factories, sewage treatment plants and other sources can release into protected water bodies.

While this court has not been friendly to regulation in recent years, I believe the practical impact of this decision remains to be seen, and that it is not the major blow to clean water protection that some observers feared the court would inflict. In particular, the court affirmed that permitting agencies can still impose nonnumeric requirements, such as prohibitions on polluting at a certain time or under certain weather conditions like rain or high heat.

Standards for treating sewage

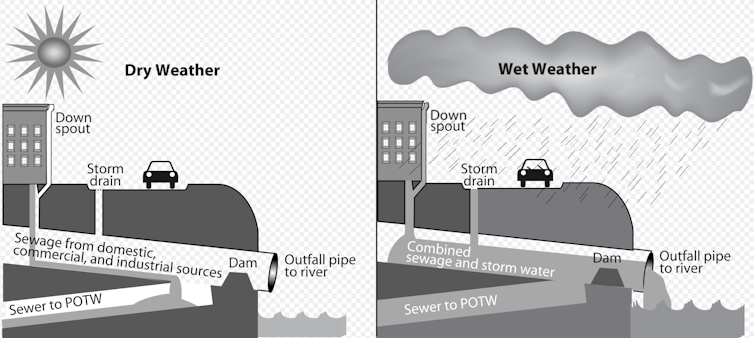

The 1972 Clean Water Act prohibits any “discharge of a pollutant” without a permit into bodies of water, such as rivers, lakes and bays, that are subject to federal regulation. San Francisco has a combined sewage treatment plant and stormwater control system, the Oceanside plant, which discharges treated sewage and stormwater into the Pacific Ocean through eight pipes, or outfalls.

The California State Water Resources Control Board is in charge of seven outfalls that release treated water close to shore, in state waters. But the facility’s main pipe discharges into federal waters more than 3 miles out to sea, so it is regulated by the EPA.

To comply with the law, polluters must obtain permits through the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System. The city and county of San Francisco have held a permit for the Oceanside facility since 1997.

Discharge permit requirements can be both quantitative and qualitative. For example, the EPA establishes standard effluent limitations that dictate how clean the discharger’s waste stream must be. The agency sets these technology-based limitations according to the methods available in the relevant industry to clean up polluted wastewater.

Numeric targets tell the discharger clearly how to comply with the law. For example, sewage treatment plants must keep the pH value of their wastewater discharges between 6.0 and 9.0. As long as the plant meets that standard and other effluent limitations, it is in compliance.

What counts as ‘clean’?

A second approach focuses not on the specific content of the discharge but rather on setting standards for what counts as a “clean” water body.

Under the Clean Water Act, Congress gives states authority to establish water quality standards for each water body within their territory. First, the state identifies the uses it wants the ocean, river, lake or bay to support, such as swimming, providing habitat for fish or supplying drinking water.

Next, state regulators determine what characteristics the water has to have to support those uses. For example, to support cold-water fish such as perch and pike, the water may need to remain below a certain temperature. These characteristics become the water quality criteria for that water body.

Sometimes technology-based effluent limitations in a polluter’s permit aren’t stringent enough to ensure that a water body meets its water quality standards. When that happens, the Clean Water Act requires the permitting agency to adjust its permit requirements to ensure that water quality standards are met.

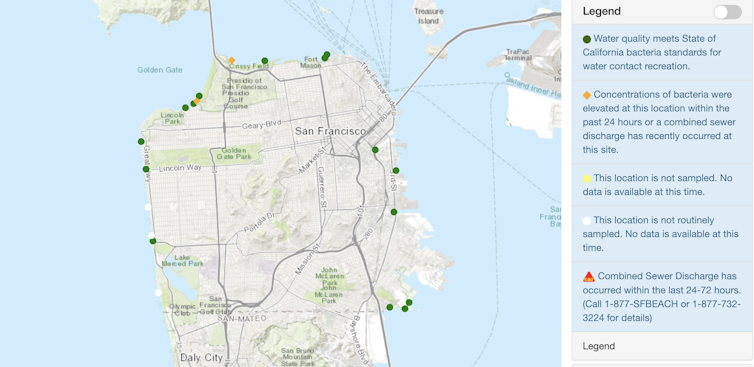

That’s what happened with the Oceanside plant. During rainstorms, runoff sometimes overwhelms the plant’s sewage treatment system, dumping a mixture of sewage and storm runoff directly into the Pacific Ocean – an event known as a combined sewer overflow. These episodes can cause violations of water quality standards. Area beaches sometimes are closed to swimming when bacterial counts in the water are high.

These aren’t small-scale releases. In a separate legal action, the federal government and the state of California are suing San Francisco for discharging more than 1.8 billion gallons of sewage on average every year since 2016 into creeks, San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean.

Can regulators say ‘Don’t violate water quality standards’?

When the EPA and California issued the Oceanside plant’s current permit in 2019, they included two general standards. The first requires that Oceanside’s “[d]ischarge shall not cause or contribute to a violation of any applicable water quality standard.” The second states that “[n]either the treatment nor the discharge of pollutants shall create pollution, contamination, or nuisance” as defined under California law.

The city and county of San Francisco argued that their permit terms weren’t fair because they couldn’t tell how to comply. For its part, the EPA invoked Section 1311(b)(1)(C) of the Clean Water Act, which allows permit writers to insert “any more stringent limitation, including those necessary to meet water quality standards,” into the permit. The agency argued that this phrase allows for narrative permit terms – a position that was upheld by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit.

In a 5-4 decision, Justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts, with Justice Neil Gorsuch concurring, agreed with San Francisco that the EPA did not have the authority to issue permits that made the city and county responsible for overall water quality. Rather, they held, EPA should set limits on the quantities of various pollutants that San Francisco was allowed to discharge.

“Determining what steps a permittee must take to ensure that water quality standards are met is the EPA’s responsibility, and Congress has given it the tools needed to make that determination,” the majority stated.

Justices Amy Coney Barrett, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson dissented. “When the technology-based effluent limitations are insufficient to ensure that the water quality standards are met, EPA has supplemental authority to impose further limitations,” they argued in an opinion authored by Barrett.

There’s an important angle that neither the majority opinion nor the dissent addressed. Under Section 1312 of the Clean Water Act, when standard industry-wide effluent limitations are not stringent enough to protect the quality of a particular water body, regulatory agencies are required to come up with more stringent limits, which are known as water quality-based effluent limitations. For example, if a sewage treatment plant is discharging into a pristine mountain lake, it might be subject to these more stringent limitations to keep the lake pristine.

Going forward, the EPA and states to which it has delegated authority will have to revise all Clean Water Act permits that contain the offending “don’t violate water quality standards” directive. These fixes will probably happen as those permits are renewed, which the law requires every five years.

What if water pollution remains a serious problem, as it has in San Francisco? Regulators could choose to generate water quality-based effluent limitations, impose more stringent numeric requirements, or simply ignore potential violations of water quality standards. Their actions will likely vary depending on each agency’s resources and on how seriously pollution discharges threaten relevant water bodies and the humans and wildlife that use them.

This is an updated version of an article originally published Oct. 11, 2024.

Robin Kundis Craig has been a member of three National Research Council committees on the Clean Water Act and is a member of the American College of Environmental Law and the Environmental Law Institute, for whom she occasionally provides Clean Water Act analyses.

Read These Next

Winter Olympians often compete in freezing temperatures – physiology and advances in materials scien

While physical exertion helps athletes stay warm, sweating can lead to dehydration.

Whether it’s yoga, rock climbing or Dungeons & Dragons, taking leisure to a high level can be good f

When a hobby becomes something larger, with a focus on improving skills and developing deep knowledge,…

Federal and state authorities are taking a 2-pronged approach to make it harder to get an abortion

Four years after the Supreme Court’s Dobbs ruling gave states the power to ban abortion, further restrictions…