Why is water different colors in different places?

Blue, green orange, brown − water comes in many colors, depending on what’s in it.

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why is water different colors in different places? – Gina T., age 12, Portland, Maine

What do you picture when you think of water? An icy, refreshing drink? A crystal-blue ocean stretching to the horizon? A lake reflecting majestic mountains? Or a small pond that looks dark and murky?

You would probably be more excited to swim in some of these waters than in others. And the ones that seem cleanest would probably be the most appealing. Whether or not you realize it, you are applying concepts in physics, biology and chemistry to decide whether you should leap in.

The color of water offers information about what’s in it. As an engineer who studies water resources, I think about how I can use the color of water to help people understand how polluted lakes and beaches are, and whether they are safe for swimming and fishing.

Light and the color of water

Drinking water normally looks clear, but ponds, rivers and oceans are filled with floating particles. They may be tiny fragments of dirt, rock, plant material or other substances.

These particles are often carried into the water during storms. Any rainfall that hits the ground and doesn’t go into the soil becomes runoff, flowing downhill until it reaches an open body of water and picking up loose materials along the way.

Particles in water interact with radiation from the Sun shining on the water’s surface. The particles can either absorb this radiation or reflect it in a different direction – a process known as scattering. What we see with our eyes is the fraction of radiation that is scattered back out of the water’s surface. It strongly affects how water looks to us, including its color.

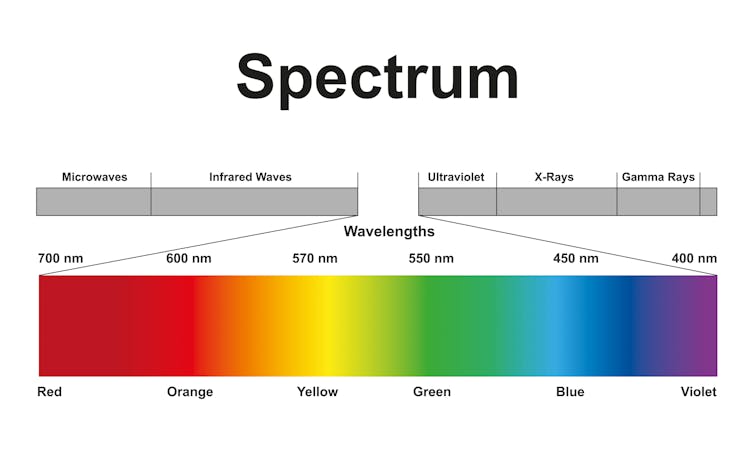

Depending on the properties of the particles in our water sample, they will absorb and scatter radiation at different wavelengths. The light’s wavelength determines the color we see with our eyes.

Waters that contain lots of sediment – such as the Missouri River, nicknamed the “Big Muddy” – backscatter light across the yellow to red range. This makes the water appear orange and muddy.

Cleaner, more pure water backscatters light in the blue range, which makes it look blue. One famous example is Crater Lake in Oregon, which lies in a volcanic crater and is fed by rain and snow, without any streams to carry sediment into it.

Deep waters like Crater Lake look dark blue, but shallow waters that are very clear, such as those around many Caribbean islands, can appear light blue or turquoise. This happens because light reflects off the white, sandy bottom.

When water contains a lot of plant material, chlorophyll – a pigment plants make in their leaves – will absorb blue light and backscatter green light. This often happens in areas that contain a lot of runoff from highly developed areas, such as Lake Okeechobee in Florida. The runoff contains fertilizer from farms and lawns, which is made of nutrients that cause plant growth in the water.

Finally, some water contains a lot of material called color-dissolved organic matter – often from decomposing organisms and plants, and also human or animal waste. This can happen in forested areas with lots of animal life, or in heavily populated areas that release wastewater into streams and rivers. This material mostly absorbs radiation and backscatters very little light across the spectrum, so it makes the water look very dark.

Bad blooms

Scientists expect water in nature to contains sediments, chlorophyll and organic matter. These substances help to sustain all living organisms in the water, from tiny microbes to fish that we eat. But too much of a good thing can become a problem.

For example, when water contains a lot of nutrients and heats up on bright sunny days, plant growth in the water can get out of control. Sometimes it causes harmful algal blooms – plumes of toxic algae that can make people very sick if they swim in the water or eat fish that came from it.

When water bodies become so polluted that they threaten fish and plants, or humans who drink the water, state and federal laws require governments to clean them up. The color of water can help guide these efforts.

My students and I collect water samples at High Rock Lake, a popular spot for swimming, boating and fishing in central North Carolina. Because of high chlorophyll levels, algal blooms are occurring there more often. Residents and visitors are worried that these blooms will become harmful.

Using satellite photos of the lake and our sampling data, we can produce water quality maps. State officials use the maps to track chlorophyll levels and see how they change in space and time. This information can help them warn the public when there are algal blooms and develop new rules to make the water cleaner.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Courtney Di Vittorio receives funding from the North Carolina Attorney General's Office Environmental Enhancement Grant Program (award WFU021PRE1) to collect data at High Rock Lake, NC. She is affiliated with the Yadkin Riverkeepers, an environmental advocacy not-for-profit group, and the North Carolina Lake Management Society.

Read These Next

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…

Formerly incarcerated Black men say they’re ‘doing OK’ while trying to cope with depression and PTSD

A nurse scientist interviewed 29 formerly incarcerated Black men in Philadelphia to understand…

Iran’s targeting of airport, ports and hotels in reaction to US strikes has forced Gulf nations onto

Qatar, the UAE and other Gulf nations have spent years cultivating an image of being an oasis of stability…