Bats in Colorado face fight against deadly fungus that causes white-nose syndrome

Numerous bats have been found in Colorado with white-nose syndrome. The fungus has killed millions of bats in North America, leaving biologists concerned about its impact on bats in the state.

Bat populations in Colorado may be headed for a decline that could cause ecological disruptions across the state.

Two bats discovered in Boulder County in late February 2024 were confirmed to have white-nose syndrome, a deadly fungal disease. Additional bats in Larimer County also tested positive for white-nose syndrome early this spring.

The first North American bats with white fungus on their faces, ears and wings were discovered in 2006 in caves where they hibernated near Albany, New York. The fungus causes bats to lose nutrients and moisture through their skin and to wake early from hibernation in search of food and water.

The disease spread west quickly, reaching Washington state in 2015 and California four years later. It was confirmed in Montana and New Mexico by 2021. Evidence of the fungus was first reported in Colorado in the summer of 2022.

I’m a bat biologist, and most of my research has focused on the genetics of Myotis bats. Knowing which bat populations are genetically unique and where they’re found will help researchers understand how white-nose syndrome will affect them and how it moves among geographic areas.

What is white-nose syndrome?

White-nose syndrome is the result of infection by a fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans.

Most fungi thrive in warm, moist conditions, but Pseudogymnoascus destructans is a “cold-loving” fungus. This trait makes it well adapted to grow on bats when their body temperatures are lowered during hibernation and their immune systems are suppressed.

Bats infected with Pseudogymnoascus destructans lose nutrients and fat reserves critical to surviving winter hibernation as the fungus grows into their skin. One of the earliest signs of white-nose syndrome is when bats awake early from hibernation in search of food. The fungus also affects other metabolic factors, such as electrolyte levels.

After the discovery of Pseudogymnoascus destructans in North America, scientists searched for the fungus around the globe and found it in European and Asian caves, where they believe it is native. Bats in those areas don’t seem to be negatively affected by the fungus, likely because they co-evolved with the fungus and developed some immunity.

Pseudogymnoascus destructans was probably brought to the U.S. by travelers who explored caves in Europe and returned with contaminated equipment.

Myotis species could face declines

Among the species most affected by white-nose syndrome are members of the diverse group of Myotis bats that I study. The majority of North American Myotis bats are found in Western states, including Colorado.

Sixteen of North America’s 45 bat species are Myotis bats. Of those 16, 11 live only in Western North America and seven live in Colorado.

All of those Myotis bats could face massive population declines if exposed to white-nose syndrome.

Some North American bat species have lost more than 90% of their population to white-nose syndrome since 2006, including two found in Colorado:

Little brown bats, Myotis lucifugus, which are being considered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for listing as endangered but are not listed yet.

Tricolored bats, Perimyotis subflavus, which are proposed as endangered, a status which indicates that the species is in danger of extinction and is awaiting a final determination to be on the endangered species list.

Colorado testing for white-nose syndrome

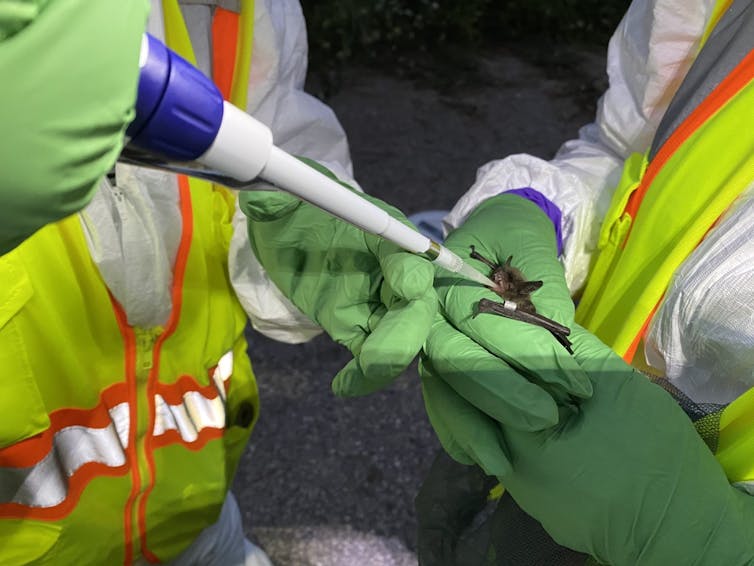

Colorado Parks and Wildlife has been testing for Pseudogymnoascus destructans since 2019.

In the summer of 2022, 25 bats at Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site in Otero County were tested. Only one, a Yuma bat (Myotis yumanensis) was positive for the fungus, though it showed no signs of disease.

A year later, in July 2023, a second Yuma bat at Bent’s Old Fort had signs of the fungus on its wings and was euthanized by the National Park Service. It was the first bat in Colorado confirmed with the disease.

Preventing further spread

Since the disease is highly infectious in Eastern bats, finding even one Colorado bat with white-nose syndrome rings alarm bells. But biologists know little about population structure, hibernation sites and hibernation behaviors of most Western Myotis species. This is a major barrier to understanding the potential impact of white-nose syndrome on bats in Colorado.

Researchers think Western Myotis bats might hibernate at smaller sites, unlike many Eastern bats that hibernate in large mines and dams. This behavior might mitigate the impact of the disease in the West, since groups that hibernate together may be smaller, resulting in limited opportunities for disease spread.

Researchers also lack information on the genetic structure of Western populations of Myotis bats, which is a critically important aspect of management and conservation strategies.

Genetic research I published with a group of colleagues shows strong evidence that biologists are underestimating the number of Western Myotis species because of a phenomenon called “cryptic,” or hidden, species. This research suggests there are Myotis bats that are similar in size and shape but genetically different. Since most species are identified by morphological characteristics, the number of species recognized by science is likely too low.

For instance, little brown bats are currently considered a single species, though research has found five independent lineages within this species.

The cryptic species most affected by white-nose syndrome in the East is Myotis lucifugus lucifugus.

Two of these cryptic species – M. l. lucifugus and M. l. carissima – live along the Front Range in Wyoming and Colorado, so it is possible that bat-to-bat contact between them is happening there and spreading the disease.

What’s next for bats in Colorado?

Biologist John Demboski at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science and I are teaming up to analyze genetic samples from across Colorado. We will analyze tissues from sick bats in Boulder and Larimer counties along with a large genetic dataset of Myotis bats from across the state.

The results of our DNA analyses will help predict how white-nose syndrome may spread through Colorado bat populations and where to target efforts to protect them. Specifically, the results will clarify where the two cryptic species occur in the state and, therefore, where disease transmission could be occurring.

A few promising developments:

The U.S. Geological Survey recently developed a vaccine against white-nose syndrome and is currently assessing its efficacy. Its promise is currently limited, however, because using the vaccine requires all bats to be captured and given an oral dose of the medication, a nearly impossible task for wild-ranging, nocturnal animal populations.

Some preliminary studies on Eastern populations of little brown bats suggest that they may be building a resistance to the fungus. A small number survive.

Even if bats do recover, rebuilding populations will take a long time. Most female bats produce just one offspring per year over their life spans, which can range from 10 to more than 30 years. And most bat populations face other threats to survival, such as habitat destruction, threats to prey populations and persecution.

Tanya Dewey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Kansas revoked transgender people’s IDs overnight – researchers anticipate cascading health and soci

With invalid driver’s licenses and birth certificates, transgender people are at risk for more than…

Massive US attacks on Iran unlikely to produce regime change in Tehran

President Trump has appealed to Iranians to topple their government, but a popular uprising is unlikely…

Iran will respond to US-Israeli strikes as existential threats to the regime – because they are

The latest attack on Iran goes far beyond previous operations by Israel and the US in both scale and…