Houston area’s flood problems offer lessons for cities trying to adapt to a changing climate

Too much pavement and old drainage systems are just two of the problems communities face.

Scenes from the Houston area looked like the aftermath of a hurricane in early May after a series of powerful storms flooded highways and neighborhoods and sent rivers over their banks north of the city.

More than 400 people had to be rescued from homes, rooftops and cars, according to The Associated Press. Huntsville registered nearly 20 inches of rain from April 29 to May 4, 2024.

Floods are complex events, and they are about more than just heavy rain. Each community has its own unique geography and climate that can exacerbate flooding. On top of those risks, extreme downpours are becoming more common as global temperatures rise.

I work with a center at the University of Michigan that helps communities turn climate knowledge into projects that can reduce the harm of future climate disasters. Flooding events like the Houston area experienced provide case studies that can help cities everywhere manage the increasing risk.

Flood risks are rising

The first thing recent floods tell us is that the climate is changing.

In the past, it might have made sense to consider a flood a rare and random event – communities could just build back. But the statistical distribution of weather events and natural disasters is shifting.

What might have been a 1-in-500-years event may become a 1-in-100-years event, on the way to becoming a 1-in-50-years event. When Hurricane Harvey hit Texas in 2017, it delivered Houston’s third 500-year flood in the span of three years.

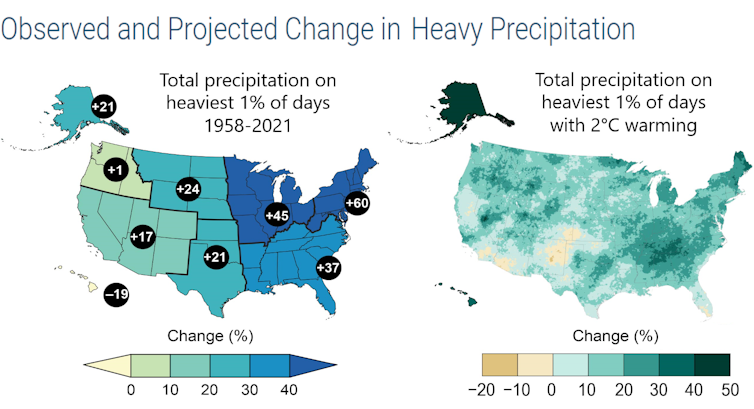

Basic physics points to the rising risks: Global greenhouse gas emissions are increasing global average temperatures. Warming leads to increasing precipitation and more intense downpours, and increased flood potential, particularly when storms hit on already saturated ground.

Communities aren’t prepared

Recent floods are also revealing vulnerabilities in how communities are designed and managed.

Pavement is a major contributor to urban flooding, because water cannot be absorbed and it runs off quickly. The Houston area’s frequent flooding illustrates the risks. Its impervious surfaces expanded by 386 square miles between 1997 and 2017, according to data collected by Rice University. More streets, parking lots and buildings meant more standing water with fewer places for rainwater to sink in.

If the infrastructure is well designed and maintained, flood damage can be greatly reduced. However, increasingly, researchers have found that the engineering specifications for drainage pipes and other infrastructure are no longer adequate to handle the increasing severity of storms and amounts of precipitation. This can lead to roads being washed out and communities being cut off. Failures in maintaining infrastructure, such as levees and storm drains, are a common contributor to flooding.

In the Houston area, reservoirs are also an essential part of flood management, and many were at capacity from persistent rain. This forced managers to release more water when the storms hit.

For a coastal metropolis such as the Houston-Galveston area, rapidly rising sea levels can also reduce the downstream capacity to manage water. These different factors compound to increase flooding risk and highlight the need to not only move water but to find safe places to store it.

The increasing risks affect not only engineering standards, but zoning laws that govern where homes can be built and building codes that describe minimum standards for safety, as well as permitting and environmental regulations.

By addressing these issues now, communities can anticipate and avoid damage rather than only reacting when it’s too late.

Four lessons from case studies

The many effects associated with flooding show why a holistic approach to planning for climate change is necessary, and what communities can learn from one another. For example, case studies show that:

Floods can damage resources that are essential in flood recovery, such as roads, bridges and hospitals. Considering future risks when determining where and how to build these resources enhances the ability to recover from future disasters. Jackson, Mississippi’s water treatment plant was knocked offline by flooding in 2022, leaving people without safe running water. Houston’s Texas Medical Center famously prepared to manage future flooding by installing floodgates, elevating backup generators and taking other steps after heavy damage during Tropical Storm Allison in 2001.

Flood damage does not occur in isolation. Downpours can trigger mudslides, make sewers more vulnerable and turn manufacturing facilities into toxic contamination risks. These can become broad-scale dangers, extending far beyond individual communities.

It is difficult for an individual or a community to take on even the technical aspects of flood preparation alone – there is too much interconnectedness. Protective measures like levees or channels might protect one neighborhood but worsen the flood risk downstream. Planners should identify the appropriate regional scale, such as the entire drainage basin of a creek or river, and form important relationships early in the planning process.

Natural disasters and the ways communities respond to them can also amplify disparities in wealth and resources. Social justice and ethical considerations need to be brought into planning at the beginning.

Learning to manage complexity

In communities that my colleagues and I have worked with, we have found an increasing awareness of the challenges of climate change and rising flood risks.

In most cases, local officials’ initial instinct has been to protect property and persist without changing where people live. However, that might only buy time for some areas before people will have little option but to move.

When they examine their vulnerabilities, many of these communities have started to recognize the interconnectedness of zoning, storm drains and parks that can absorb runoff, for example. They also begin to see the importance of engaging regional stakeholders to avoid fragmented efforts to adapt that could worsen conditions for neighboring areas.

This is an updated version of an article originally published Aug. 25, 2022.

Richard Rood receives funding from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Science Foundation. He is a co-principal investigator at the Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessment Center at the University of Michigan.

Read These Next

Massive US attacks on Iran unlikely to produce regime change in Tehran

President Trump has appealed to Iranians to topple their government, but a popular uprising is unlikely…

Drug company ads are easy to blame for misleading patients and raising costs, but research shows the

Officials and policymakers say direct-to-consumer drug advertising encourages patients to seek treatments…

Nanoparticles and artificial intelligence can help researchers detect pollutants in water, soil and

Tiny particles bounce light around in a unique way, a property that researchers are using to detect…